Process to Product : A Technical Investigation into the Working Practices of Albert Moore

Ruby Awburn, Sophie Lynford, and Georgina Rayner

Introduction

In 1868 the British artist Albert Moore (1841–93) wrote to his patron Frederick Leyland to clarify his preferences with regards to an in-progress commission. Moore explained that in planning the composition he had “made five designs in chalk and in color, in as many weeks.” The decision at hand was the projected dimensions of the canvas, which would feature a female nude at life size. Moore assured Leyland, however, that the scale was flexible: “The cartoon not being yet made, a change in the dimensions of the picture is quite possible.”1

This letter records one of the few descriptions in the artist’s own words of his complicated working process. Of Moore’s contemporaries associated with the Aesthetic movement, most notably his friend James McNeill Whistler, many wrote essays and delivered lectures on their artistic philosophies and praxes.2 Moore, however, was notoriously reclusive and offered no such treatises. His paintings, as Robyn Asleson has persuasively argued, “serve as his only manifesto and his most eloquent epitaph.”3

The majority of what is known of Moore’s methods is due to Alfred Lys Baldry, the painter, art critic, and student of Moore, who wrote a biography of his former teacher in 1894. Published a year after Moore’s death, the volume was the first to document the artist’s multi-step painting practice in which substantial preparatory drawings were produced, including designs in chalk, gridded graphite sketches, pounced cartoons, and oil studies. Drawing was central to Moore’s process—at least seven distinct stages relied on drawings and their subsequent transfer to canvas. The benefits of careful draftsmanship had been instilled in him from childhood. His elder brother, the painter Henry Moore, with whom Albert was close, wrote that “Drawing is the beginning of everything. It is almost like the discovery of a new sense, and from the time we begin to draw objects we begin to discover their beauties.”4

Albert Moore’s artistic project has long been described, both in his own time and today, as a search for ideal beauty. The art critic Sidney Colvin regarded his subjects as “merely a mechanism for getting beautiful people into beautiful situations.”5 Determining the precise combination of figures, draperies, and palettes occupied the artist anew each time he began a composition. The process is recorded in his surviving preparatory materials, especially his work on paper. But several stages that were critical to the artist’s practice are not represented by distinct products because they were effaced by subsequent steps. For example, Baldry explains that Moore applied successive “priming[s] of white lead” to his canvas mid-way through executing a painting, all but obscuring initial layers of color beneath.6

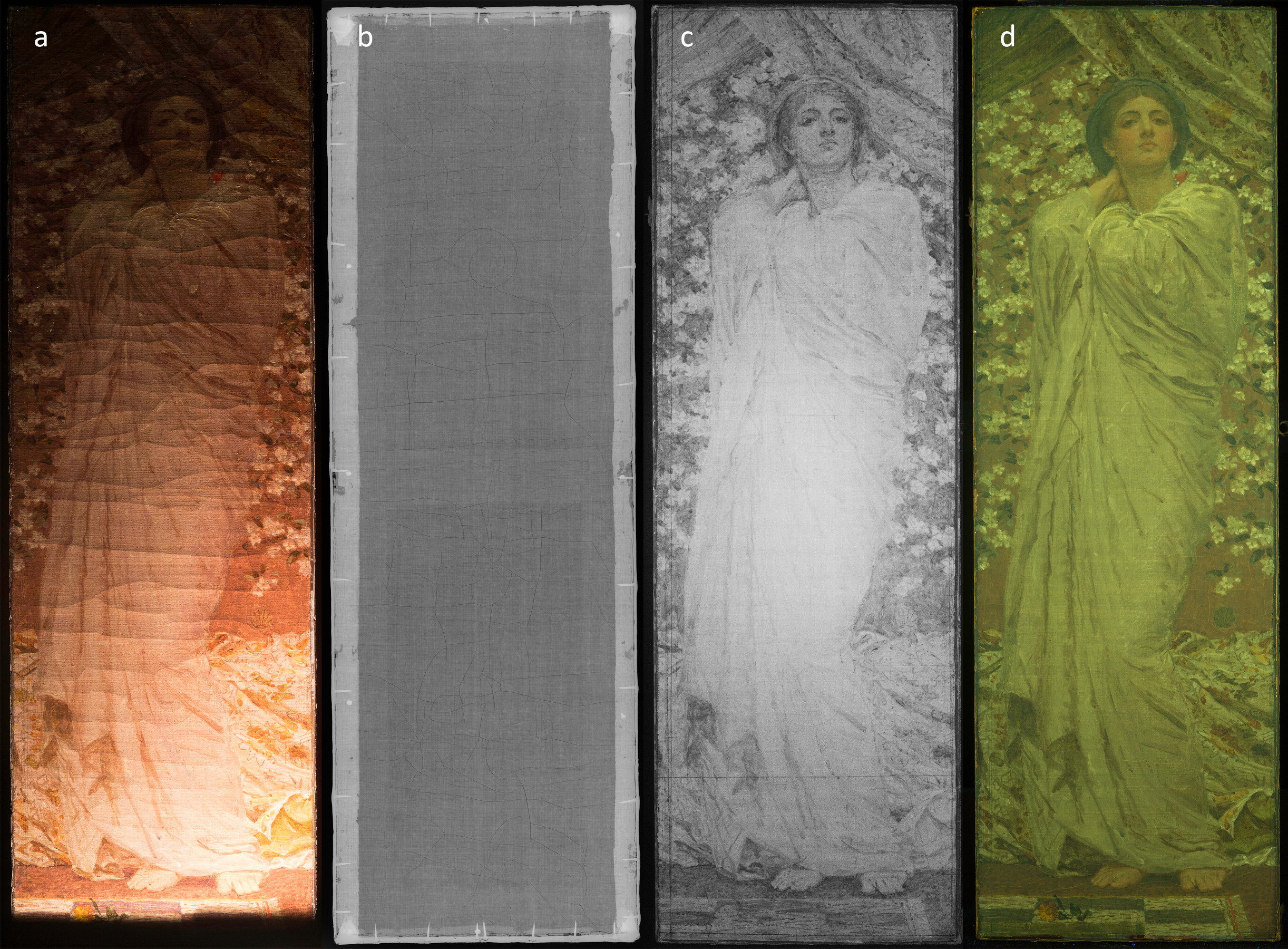

The iterative and substitutive dimension of Moore’s working practice make his paintings ideal candidates for technical and scientific analysis. This article presents the findings of such research performed on Study for “Blossoms” (Fig. 1), an oil study by Moore in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums. This research presents evidence that documents stages of Moore’s artistic process that had been previously adumbrated in Baldry’s biography. The combination of scientific analysis, archival research, and an experimental reproduction of the artist’s process has offered a unique opportunity to better understand Moore’s artistic practice. Such interdisciplinary collaboration has enabled the authors to confirm the accuracy of his student’s account while also illuminating one of the most complex artistic practices of the Victorian era.

Artistic Labor in Victorian Britain

During his thirty-year career, Moore rarely strayed from the compositional schema for which he was known. His oeuvre is comprised primarily of narrow, vertical canvases featuring slender women draped in classicized garments and placed in shallow decorative settings. His titles often reference a secondary focus of the composition. Such titles as Azaleas (1867-68, Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art), Birds (1878, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery), and Acacias (ca. 1880, Carnegie Museum of Art) underscore his works’ still life qualities and distance the viewer from any readily identifiable narrative.

Study for “Blossoms” is one of at least two known oil studies for the large-scale, near life-size painting, Blossoms (Fig. 2). The composition features the hallmarks of Moore’s output: willowy female figure; draped diaphanous textile; and floral background. Baldry believed the work to be “one of the most severely beautiful of all the paintings of [Moore’s] middle period, a study of scrupulous refinement, an expression of almost classical simplicity.”7 Moore’s mastery of rendering the pleating and gathering of drapery is on display in the figure’s rose robes, the coral curtains above her head, and the white sheet strewn atop the bench. While many of his works feature figures placed within a room or landscape, Blossoms belongs to a group of paintings in which an intricately patterned textile or spray of flowers constitute the background. The titular blossoms cascade across the surface of the canvas, simultaneously blocking the viewer’s entry into the world of the figure while calling attention to the artist’s painstaking and minute facture.

Though Moore never published his own explanation of his working methods, he participated in a larger conversation about artistic labor that occupied the Victorian art world during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Moore was one of three witnesses to testify on behalf of Whistler in the libel suit that Whistler brought against the critic John Ruskin in 1878. The previous year, Ruskin published a review of Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1872-77, Detroit Institute of Arts). Condemning the work’s lack of finish, Ruskin accused the artist of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”8 Whistler claimed the piece slandered his reputation and sued for damages.

In his testimony, Moore entered the period debate concerning the relationship between an artist’s labor and an artwork’s value. At the center of the Whistler-Ruskin trial were questions about whether Whistler’s loosely painted and nearly non-representational landscapes, which he referred to as “arrangement[s] of line, form, and color,” constituted art and, specifically, whether the work that Whistler put into each painting was worth the price he was charging.9 In his review, Ruskin had contended that Nocturne in Black and Gold was not the product of honest exertion. Moore contested this opinion on the stand, advancing a position that was contentious among many contemporaries and anticipated a refrain more commonly heard in discussions of modern art: “money is paid for the skill of the artist, not always for the amount of labour expended.”10 Whistler echoed this sentiment in the most famous pronouncement of the trial. During cross-examination, when Whistler explained it had taken two days to paint Nocturne in Black and Gold, Ruskin’s lawyer challenged him: “The labour of two days is that for which you ask two hundred guineas?” Whistler’s reply was met with applause from the gallery: “No. I ask it for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime.”11

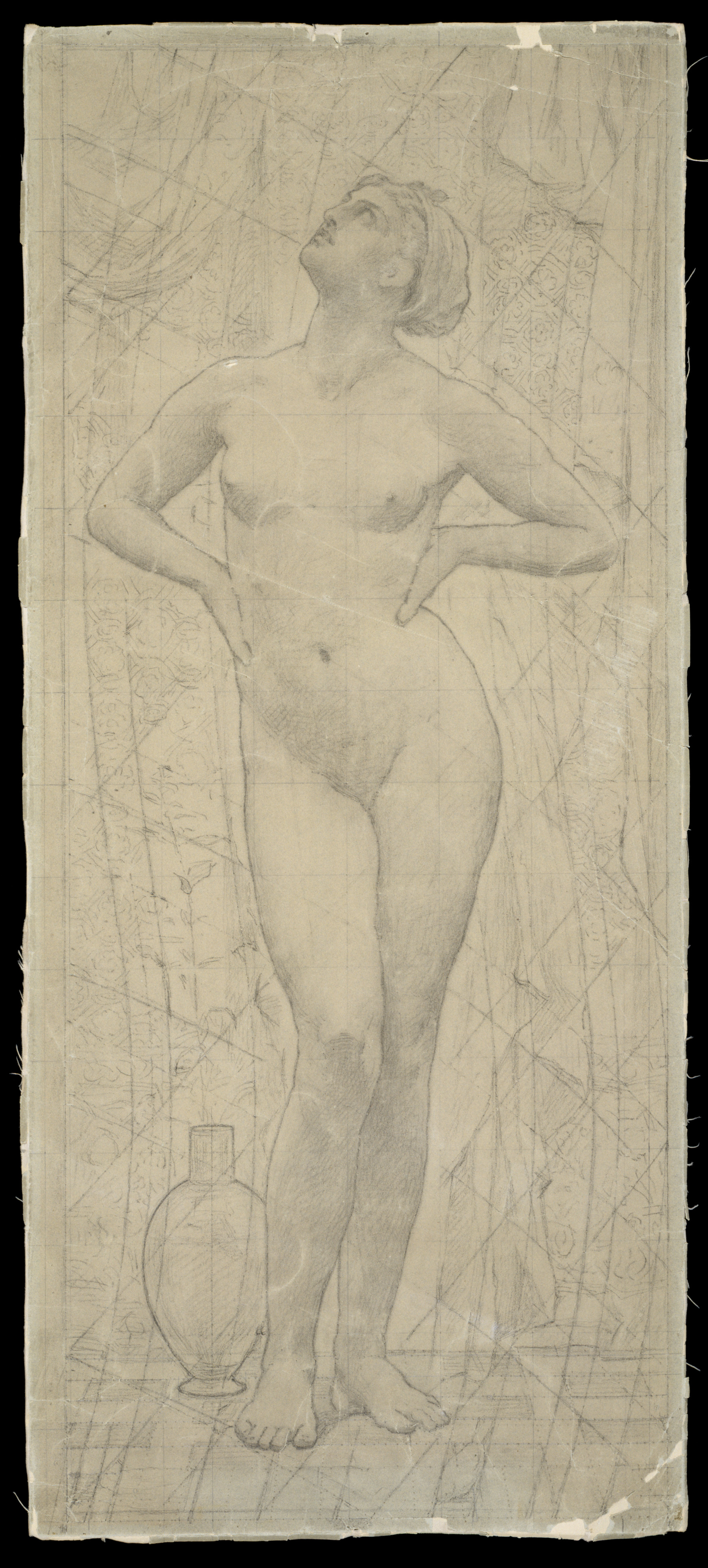

There is some irony that Moore was the painter who defended Whistler from accusations that his artistic practice was too abbreviated to be taken seriously, as Moore’s working methods were, in his own time, recognized as especially laborious. Of the numerous steps in Moore’s process that Baldry detailed in his biography, the artist’s practice of gridding has received the most sustained attention from contemporary scholars.12 Many of Moore’s preparatory drawings reveal networks of lines that intersect at irregular angles, governing the diagonals that undergird everything from his figures’ postures to the placement of their drapery’s folds. Grids formed of curved and diagonal lines were used to assemble spatially harmonious compositions and grids of perpendicular lines were used to scale up small studies.13 Sometimes he combined these “system[s] of line arrangement,” visible in Nude Figure Study for “Birds of the Air” (Fig. 3).14 In certain instances, Moore applied his grid directly onto the canvas of oil studies. For example, diagonal lines in graphite are visible below the topmost paint layer in Yellow Marguerites (Fig. 4).15

Gridded preparatory drawings were just one of the multiple discrete steps that Moore undertook to complete one of his large-scale paintings—a process that occupied several months. Baldry also details Moore’s other methods in animated, if meandering, prose. These individual steps have, to date, not been enumerated in sequence or in their entirety. At least eighteen distinct stages to Moore’s process can be identified using Baldry’s account and are offered here. This list not only attests to Moore’s discipline and industriousness but enables us to ascertain which parts of his process are represented by Moore’s surviving chalk and graphite drawings and oil studies, including Study for “Blossoms.”

Moore’s Working Method: The Steps

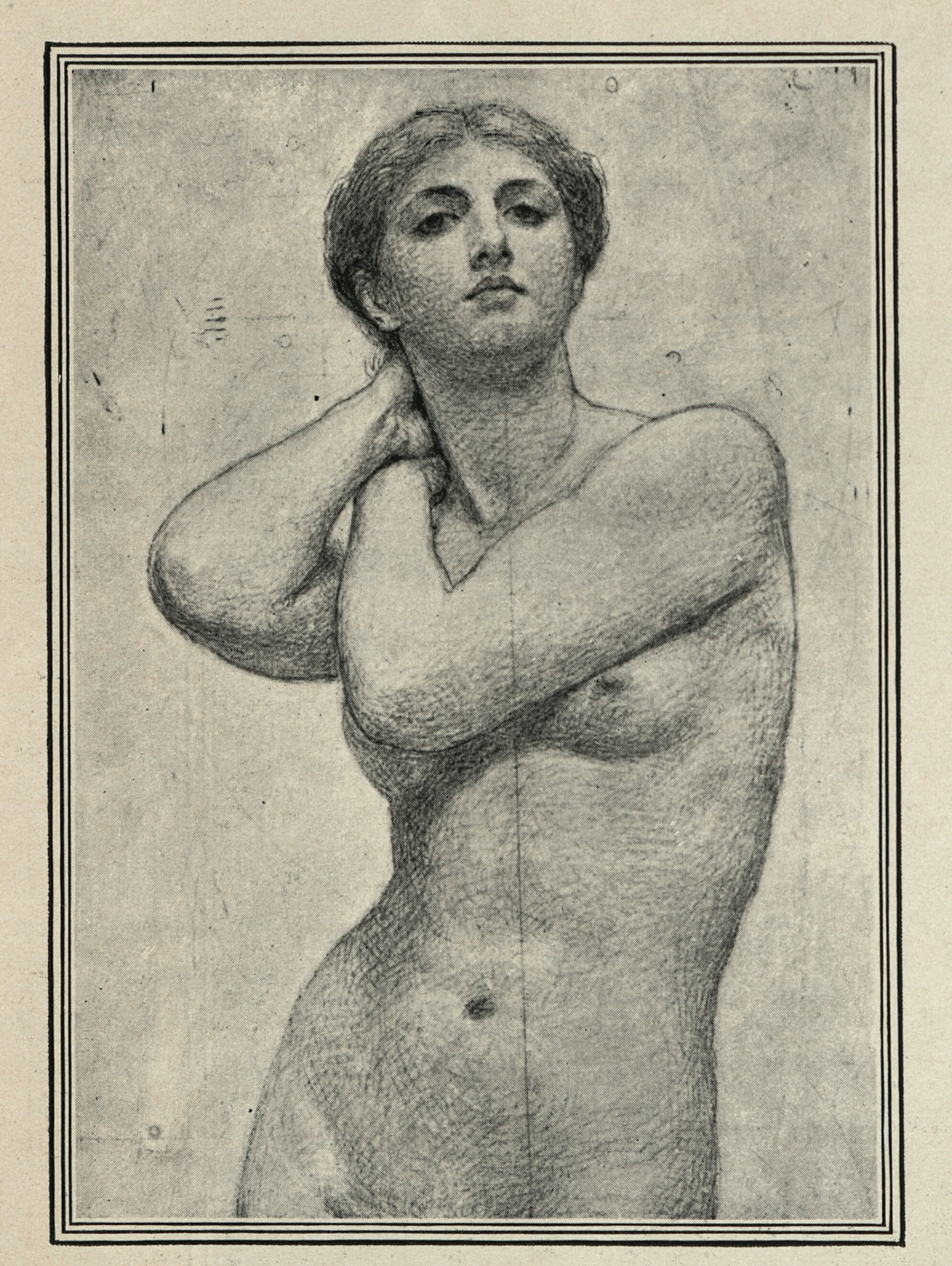

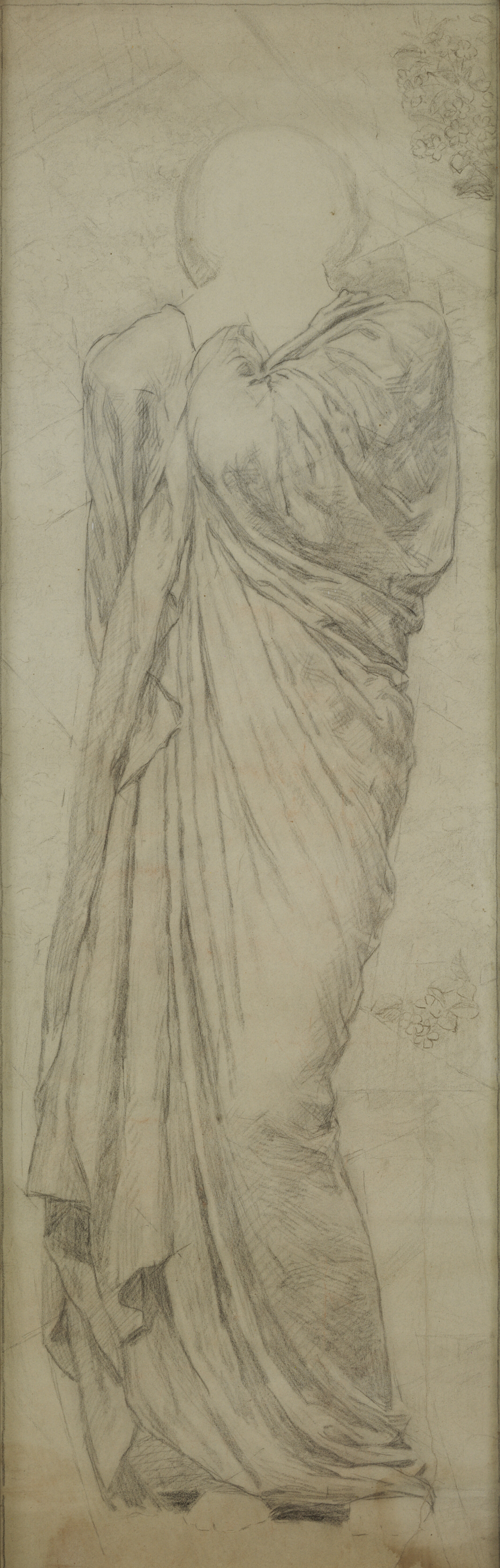

The two earliest preparatory drawings for Blossoms have yet to be located but are known through printed reproductions in period publications (Figs. 5,6). Two additional extant preparatory works include a study of drapery in charcoal on gray paper (see Fig. 8) and another oil study, smaller in scale and more loosely painted than the Harvard study (see Fig. 9). Together with Study for “Blossoms” and Blossoms, these six works represent six distinct stages in Moore’s multi-step process. Twelve additional steps were identified through Baldry’s account, technical imaging and scientific analysis, and the authors’ experimentation with Moore’s techniques. The step-by-step process of Moore’s painting practice can be understood as follows:

Observe nature and the model.

Sketch the composition in graphite or ink. (Fig. 5)

Execute gridded drawings of the composition, often in graphite, to determine color distribution and drapery positioning. (as illustrated by Fig. 3)

Complete a black and white chalk drawing of the nude figure on brown paper. (Fig. 6)

Create a black and white cartoon of the nude figure on tracing paper that is true to the size of the final canvas dimensions.

Pounce the cartoon of the nude figure to the canvas. (as illustrated by Fig. 7)

Fill out the transferred image with a wash of color.

Prepare additional canvas(es) with at least two coats of lead white, toned with transparent color to a light gray.

Transfer the nude cartoon to additional canvas(es) to experiment with color combinations and drapery arrangements.

Create a black and white cartoon of the drapery arrangement on tracing paper, which is transferred via pouncing onto the additional canvas from step 8. (Fig. 8)

Experiment with different color studies on this additional canvas. (Fig. 9)

Apply two coats of lead white priming over the color sketch on the original canvas. This step was sometimes applied directly after the nude cartoon was transferred to the canvas, before color was added.

Transfer drapery to the primed canvas via the pounced drapery cartoon.

Paint the entire composition in a light monochrome of gray.

Pin blank tracing paper over the monochrome composition.

Paint the entire composition in color on the tracing paper.

Cut the painted tracing paper away in pieces while applying color directly over the monochrome canvas.

In rare instances, apply varnish.

The visual homogeneity across Moore’s paintings can be attributed to this systematic process, which incorporated practices from the adjacent fields of architectural drafting, in which Moore had been trained, and fresco painting, which he had pursued early in his career. Born of experimentation, this procedure was time intensive and a primary driver of his career-long poverty.16 Moore explained to Leyland that, “I never find it convenient to carry on more than one picture of any moment at the same time.”17 Such a strict policy, however, ensured that Moore’s earnings on a commission always fell far short of the labor he expended.18 Indeed, during the five weeks he spent on preliminary drawings for Leyland’s A Venus (1869, York City Art Gallery)—preparatory materials that comprised only the first four steps of his process—Moore’s single-minded focus forced him to turn down “other commissions amounting to 800 guineas.”19 Around 1880 Moore—seeking to address this limitation of his practice—identified stages in his multi-step process that, with adjustments, could lead to the completion of additional works, thus increasing his income. Moore began transforming his oil studies into finished paintings, applying several of the key steps in his process to each study, Baldry explains, in order to complete it.20 Technical and scientific examination of Study for “Blossoms,” discussed in the following section, confirms that it received this treatment.

The Steps in Practice: Understanding Study for “Blossoms”

As a small-scale oil study for Blossoms, Study for “Blossoms” seems to represent steps eight through eleven, the stages in which Moore experiments on smaller canvases with different drapery arrangements and color schemes. By engaging a truncated version of his multi-step process in completing this oil study, Moore “was able to secure,” in Baldry’s words, “the look of being elaborately painted.”21 Technical imaging and scientific analysis of the work confirm that Moore applied many of his steps to this small canvas, a process originally devised for his large, finished paintings.

Canvas and Ground

Study for “Blossoms” has a dramatic tenting crack pattern travelling horizontally across its surface (Fig. 10a).22 Moore purchased lengths of rolled, pre-primed canvas from his colourman, Charles Roberson & Co.23 There is the possibility, if time elapses before the primed canvas is used, that the oil in the ground will begin polymerizing in the rolled configuration, becoming brittle before the painting is stretched. This can manifest as cupped cracks that may not become apparent until after the artist has completed the painting.24

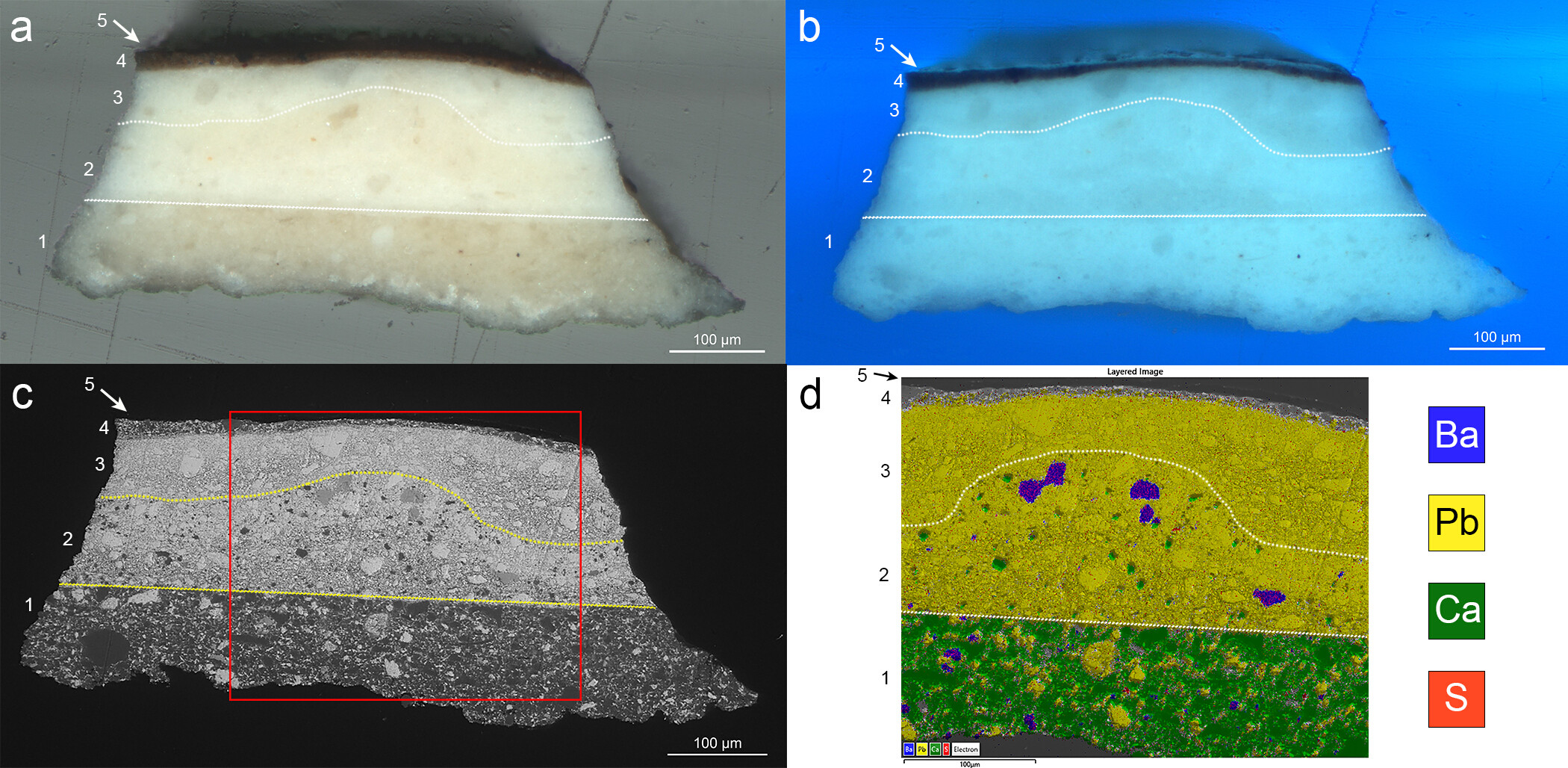

A cross-section prepared from the painting provides evidence that Moore used a commercially primed canvas for Study for “Blossoms.” The lowest layer (layer 1, Fig. 11), is perfectly level and rich in calcite with lead white and barite particles dispersed throughout. Two additional ground layers (layers 2 and 3, Fig. 11) are more uneven and vary in thickness and pigment content. The second layer is rich in lead white with barite and calcite particles. The uppermost ground layer only contains lead white which is consistent with the X-radiograph that indicated the presence of a heavy base layer of lead (Fig. 10b) and appears to have been smoothed flat. The irregularity of the boundary between the second and third layers, as highlighted by the dashed line in Fig. 11, suggests that these may have been applied by hand, on top of a commercial priming.

Moore’s alteration of the ground—his application of additional layers to provide a smooth lead white painting surface—was a popular practice during the Victorian era and was particularly employed by Moore’s Pre-Raphaelite predecessors and contemporaries. Artist treatises and instruction manuals in circulation during the nineteenth century, such as Richard St John Tyrwhitt’s A Handbook on Pictorial Art (1868), advised this type of additional surface preparation. Tyrwhitt specifically recommended applying an extra ground layer when executing an oil sketch: “it will give [the artist] good texture to work on—just as important a matter in oils as in water-colour—and it will prevent the colours sinking into the canvas when drying and make them bear out as brightly as on paper.”25

With regards to Moore’s large-scale paintings, Baldry suggests that the artist applied two additional priming layers of lead white oil paint approximately midway through his working process, atop a pounced charcoal sketch of the nude figure that had been filled out with a wash of color (step 12). In the case of Study for “Blossoms,” Moore adopted this step as his first—no evidence of charcoal was found atop the commercially applied ground.

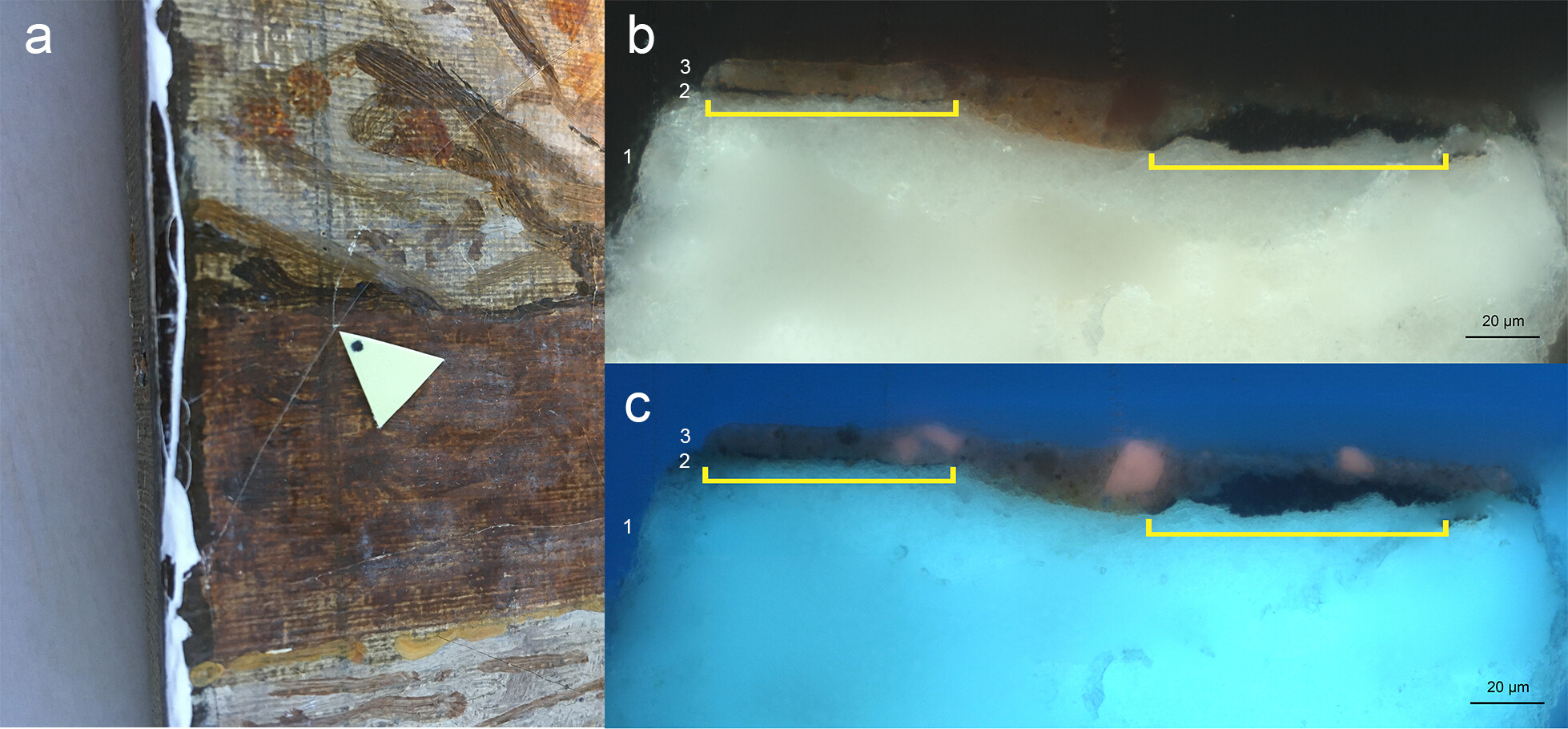

In addition to adapting his ground, Moore may have completed Study for “Blossoms” unstretched. This is suggested by a painted border that outlines the area of the composition, but which sits on the turnover edges more so than within the picture plane. Additionally, there are colored markings on the tacking margins of the painting (Fig. 12). These red, blue, and yellow paint26 strokes are placed with intention, not simply from the wiping of a brush, and seem to correspond to preparatory grid lines, discussed below. The presence of a similarly painted border on other oil studies by Moore indicates that he may have had a long bolt of unstretched canvas, pinned to a wall or board, on which he completed numerous studies before cutting them apart for stretching.27

Underdrawing

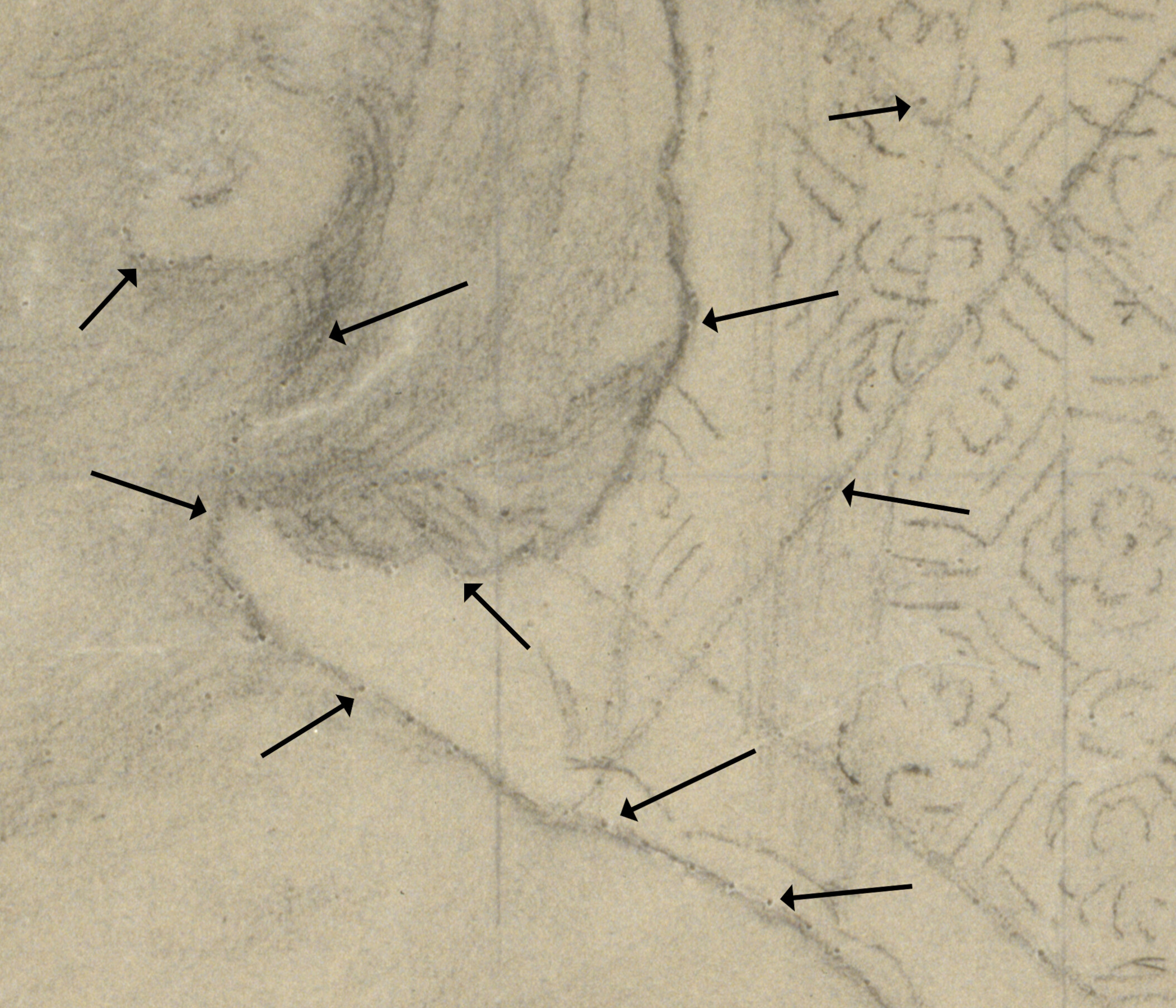

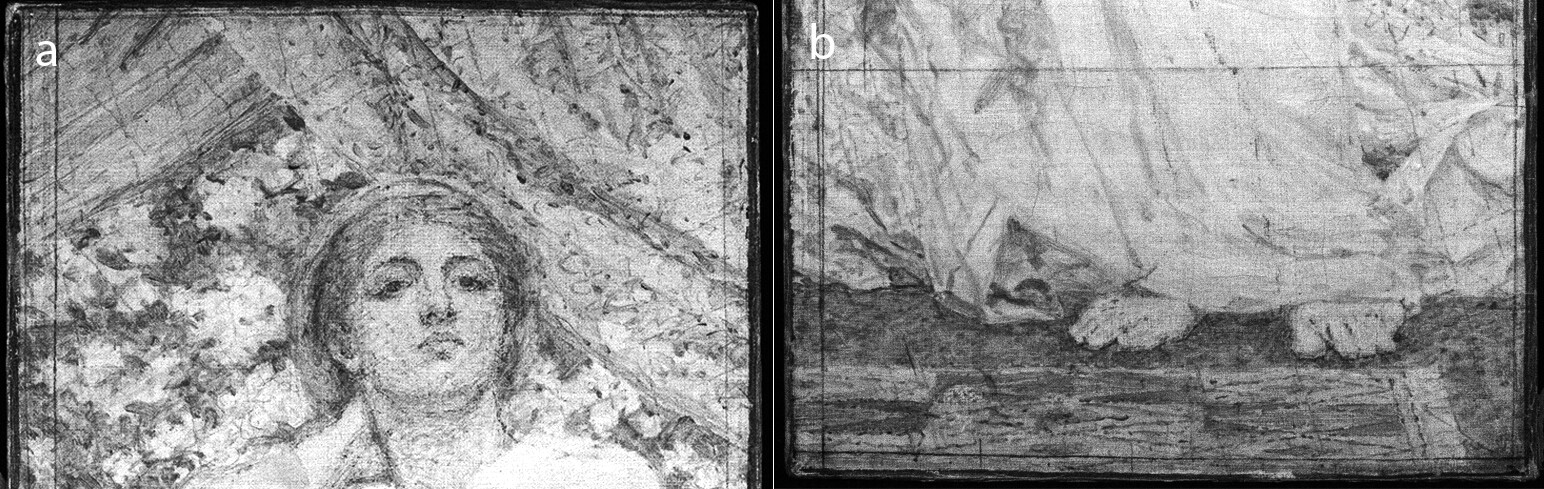

When examined with infrared reflectography (IRR), the painted surface was rendered transparent, exposing several carbon-based elements (Fig. 10c). These include an underdrawing of the figure, a ruled border, and an asymmetric and linear geometric framework that is visible near the figure’s feet and legs, and face and shoulders (Fig. 13). The underdrawing can be seen in cross-section, applied directly onto the ground in a discontinuous layer (Fig. 14, layer 2), before the colored paint layer was applied.

Moore’s use of a grid was placed by Baldry early in the artist’s process, as part of his preparatory works on paper (step 3). Further, Baldry recalled that for his oil studies Moore used “no under painting nor previous placing of details. He had only the roughly drawn outline of the nude figure to guide him.”28 However, the inclusion of the drawn grid and a ruled border outlining the composition of Study for “Blossoms” confirms that gridding remained a crucial practice beyond preliminary drawings, employed at multiple intervals throughout his process.

Paint

Considered side-by-side, Study for “Blossoms” and Blossoms appear close in composition. There are key differences, however, between the works’ palettes and paint application. Blossoms’ vibrancy derives primarily from the inclusion of the coral-red curtain and rug paired with the figure’s rose drapery. In Study for “Blossoms,” Moore engaged a more muted palette, creating his colors through mixing lead white with a small selection of pigments that included ochre, umber,29 cobalt blue, cobalt yellow, chrome green, vermilion, and an organic red.30

The figure’s robes are an ivory color that is rich in lead white with additions of ochre, umber, and cobalt blue to accentuate the folds of the fabric. Cobalt blue and iron-rich pigments (ochre and umber) are combined in varying amounts for the figure and were identified in the hat, hair, and lips. Her fair skin, rich in lead white, includes ochre and vermilion to create the blush tones. The background is a warm mauve, created with ochre pigments, and the spray of white blooms is painted similarly to the figure’s robes in both pigment composition and application. Both the curtain and the textile behind the figure’s knees are intricately ornamented with a floral design, heightened with touches of yellow, red, brown, green, and white, utilizing mixtures of cobalt yellow, chrome green, cobalt blue, and ochre. The exceptions to the muted palette are the use of pure vermilion for the seam detail on the checkered rug and the touch of red on the figure’s shoulder, and the single use of cadmium yellow for the flower casually strewn on the rug.

The floral designs and the checkered rug contribute to a visual busyness in Study for “Blossoms” that Moore resolved in Blossoms. By experimenting with colors and textures in this study, Moore arrived at a more harmoniously balanced composition in his final work, achieving modeling and the suggestion of depth through the juxtaposition of solid blocks of color. The comparatively flattened appearance of Study for “Blossoms” can be attributed, in part, to the artist’s application of a single paint layer, which is revealed in the cross-section under magnification (layer 4 in Fig. 11). This single layer contrasts with Moore’s paint application on Blossoms, which is composed of multiple thin layers.31 Despite painterly brushstrokes visible in the study’s blossom petals and fabric folds, there is minimal impasto and the paint layer appears as a thin wash in areas, particularly the drapery. Such light paint application in Study for “Blossoms” contributes to the impression that the figure dons a gauzy textile, while the building up of paint layers in Blossoms, particularly within the robes, produces passages of chiaroscuro and, as a result, the appearance of a weightier fabric. Ultimately, Moore’s study emerges as a site not only to test color variations and pictorial arrangements but also to experiment with his facture and style of paint application.

Varnish

Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photography of the painting suggested a thick natural resin varnish, indicated by the green color of the fluorescence (Fig. 10d) and mirrored in the fluorescence of the uppermost layer in the cross-section (layer 5 in Fig. 11). Analysis identified an oil varnish comprised of mastic and likely linseed oil. The cross-section further demonstrates that the varnish layer on Study for “Blossoms” is likely to be original to the painting as there is no evidence of dirt between the uppermost paint layer and the varnish and a small amount of the uppermost paint layer has been drawn into the varnish, suggesting that it was not completely dry when it was applied.

The presence of a varnish on Study for “Blossoms” is unusual based on what has previously been understood about Moore’s artistic practice. Moore rarely varnished his paintings; his large-scale Blossoms was left unvarnished. The addition of varnish to an oil study that he was completing for sale suggests the artist sought a final touch to augment the finish of this study, particularly as he had omitted steps that were central to his large-scale works, most notably the application of multiple paint layers (steps 7, 14, and 17).

Because the discolored varnish on Study for “Blossoms” was obscuring Moore’s original palette, Harvard Art Museums conservators and curators decided to reduce the original varnish and unveil the painting’s subtle color variations. While reducing the varnish, pin holes were discovered at seemingly random intervals across the face of the painting (Fig. 15). These holes are evidence of one of Moore’s most unusual practices, which Baldry described as occurring near the end of the artist’s process (step 15). When the design was finalized, Moore painted the entire composition in light shades of gray. Then, atop the canvas, he pinned tracing paper on which he painted the entire composition in his chosen color scheme. Moore would subsequently cut away sections of the painted tracing paper and, to each exposed gray area of the canvas, apply color that matched the hue of the adjacently pinned tracing paper, painting over any pin holes in the process. This method allowed the artist, as Baldry explained, “to keep the surface upon which he was actually engaged surrounded always with colour of the same force and brilliancy as he was applying to the canvas.”32

The pin holes in Study for “Blossoms” pierce both the paint layer and the ground (Fig. 16), indicating they were created after the composition was completed. Since the cross-sections reveal only a single pigmented paint layer—Moore did not first paint this study in gray—it is also possible that the artist pinned paper to the finished painting in order to trace elements of the composition that he planned to reuse in other studies or compositions. Replication was central to Moore’s artistic practice from the mid-1870s, when he began completing multiple versions of a single composition in different color schemes.33

Conclusion

Study for “Blossoms” represents both part and whole: a single preparatory object that also records multiple steps of Moore’s working process. It demonstrates that Moore’s steps were not inflexible directives. When applied to smaller-scale paintings, they could be reordered and consolidated. This combination of steps made Blossoms, in Baldry’s opinion, “one of the conspicuous successes of Albert Moore’s life.”34

Moore’s decision to begin finishing, exhibiting, and selling his oil studies can be understood as addressing instrumentalist concerns: a need to produce more salable works. However, this shift also represents more than a commercial sensibility. In the aftermath of the Whistler-Ruskin trial, there was heightened scrutiny as to whether the price asked for a painting matched the perceived labor of the artist. In the years following the trial, Moore began to publicly display preparatory materials in greater numbers, exhibiting oil studies like Study for “Blossoms,” as well as pen and ink sketches, chalk drawings, and drapery studies. This shift in practice suggests he was eager to reassure viewers and potential patrons that his paintings were the product of strenuous mental and physical work. In Study for “Blossoms,” Moore elevates process into product by translating his iterative vision into an autonomous work of art. In a striking convergence of the arguments adduced by both the trial’s plaintiff and defendant, Moore marries Whistler’s refusal to paint narrative with his own adherence to Ruskin’s prescriptions for safeguarding their nation’s cultural health: the commitment to honest, rewarding labor.

Methods

Cross-section preparation

The samples for cross-section analysis were embedded in Bio-Plastic liquid polyester casting resin (Ward’s Natural Science). Samples were ground and polished to reveal the paint stratigraphy using a Buehler Handimet 2 roll grinder with Carbimet abrasive paper rolls ranging in grit from 240-600. Samples were then polished using a Buehler Metaserv 2000 polisher with 6µm and 1µm Buehler MetaDi Monocrystalline Diamond Suspension.

Optical microscopy

The cross-sections were observed using a Zeiss Axio Imager M2m upright microscope equipped with four objectives (5x, 10x, 20x, and 50x) and a Zeiss Axiocam 512 Color digital camera. Images were captured using the Zeiss Zen 2.6 (blue edition) software. Visible light conditions utilized a halogen lamp and an EPI-polarization filter cube. Ultraviolet (UV) conditions utilized a mercury vapor lamp and a DAPI filter cube (excitation BP 450-490, beam splitter FT 510 and emission BP 515-565).

Scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-rays (SEM-EDX) spectroscopy

The cross-sections were analyzed using a JEOL JSM-6460LV SEM with an Oxford Instruments 80 mm2 X-MaxN X-ray spectrometer running the Oxford INCA software. The SEM was operated in low vacuum mode at a chamber pressure of 35 Pa, with an operating voltage of 20 kV, beam current circa 1 nA, and working distance of 10 mm. The cross-sections were not coated prior to analysis.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman analysis was conducted on the cross-sections using a Bruker Optics Senterra dispersive Raman microscope with an Olympus BX51M microscope equipped with 20x and 50x long working distance objectives and using the Bruker OPUS (version 7.5) software. The Raman spectrometer has three laser sources, 532nm, 633nm, and 785nm. The optimum laser source depends on the pigment analyzed but, in general, blue and green pigments were predominantly analyzed with the 532nm laser at 2mw or 5mW power and other colors analyzed with the 785nm laser at 10mW power.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR in transmission mode was performed using a Bruker Vertex 70 infrared bench spectrometer coupled to a Bruker Hyperion 3000 infrared microscope. Varnish samples were compressed onto a diamond cell with a stainless-steel roller prior to analysis. Using the Bruker OPUS (version 6.0) software, spectra were recorded between 4000 and 600 cm-1 at 4cm-1 spectral resolution and 32 scans per spectrum.

Pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (py-GCMS)

Py-GCMS analyses were performed using a CDS pyroprobe 5000 (platinum coil) interfaced to an Agilent Technologies 7890B GC system coupled with an Agilent Technologies 5977A MSD and using Agilent’s MassHunter GC/MS Acquisition software. The varnish samples were placed in the center of a quartz tube and 3µL of tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH, 25% in methanol) was added to the sample/s prior to pyrolysis. Pyrolysis was conducted at 600°C for ten seconds. The samples were directed onto the column (HP-5ms Ultra Inert column, 30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 µm) by helium gas in a 20:1 split ratio. The GC oven was set with an initial temperature of 40°C for 1 minute prior to increasing in 10°C/min intervals to 300°C over a 26-minute period then maintained for 20 minutes for a total acquisition time of 47 minutes.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy

XRF point analysis was conducted on the painting using a Bruker Artax XRF spectrometer with a Silicon Drift Detector (SDD) and a rhodium anode X-ray tube. The primary X-ray beam is collimated to give a spot size of 0.65mm. Using the Bruker Artax (version 7.6) software, spectra were acquired for 100 seconds live time at 50kV and 600μA.

Imaging specifications

Technical images were captured using a Canon EOS 5D Mark 4 digital camera with the IR filter removed. For regular and UV imaging, external filtration Peca 918 and Kodak 2E filters were employed. For IR imaging, an 87A IR Pass filter was attached to the camera lens. Regular illumination was achieved with two Elinchrom RX 1200 Strobes; IR by two Lowel Pro Incandescent lamps; and UV with two TripleBright 3 lamps, each with one LW370 bulb and LW filter (average output value 358 µW/cm2). The X-ray radiation source was a Comet MXR-320/26 tube with a Carestream Industrex 2mm aluminum plate, and the exposure settings were 40kV, 7mA, 3mm FOC for 170 seconds at 152.5cm focal distance. Scanning of the plate was undertaken with a high laser power, 12-bit logarithmic data scale, PMT 10, and 50-micron scan resolution.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Materia Editorial Team and two anonymous peer reviewers for their feedback and comments on this article. They are also indebted to Harvard Art Museums’ colleagues for their support on this research: Cassandra Albinson, Head of the Division of European and American Art and Margaret S. Winthrop Curator of European Art; Alison Cariens, Conservation Coordinator; Narayan Khandekar, Director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies and Senior Conservation Scientist; Erica Lawton, Staff Assistant, Division of European and American Art; Kate Smith, Conservator of Paintings and Head of Paintings Lab; and Miriam Stewart, Curator of the Collection of the Division of European and American Art. The authors are especially grateful to Katherine Eremin, the Patricia Cornwell Senior Conservation Scientist, Harvard Art Museums, for assistance with the pigment identification. Invaluable information on Moore’s Blossoms was offered by staff at the Tate: Amy Griffin, Paintings Conservator; Bronwyn Ormsby, Principal Conservation Scientist; and Joyce Townsend, Senior Conservation Scientist. Sincere thanks are also extended to Rowan Frame for fruitful conversations on Moore’s painting techniques and for generously sharing her research on Moore’s account in the archives of Charles Roberson & Co., Hamilton Kerr Institute, Cambridge, UK.

Authors’ Bios

Ruby Awburn is the Assistant Paintings Conservator at the Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), Brisbane, Australia. She was formerly the Richard I. Shader Fellow in Paintings Conservation in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museums.

Sophie Lynford is the Theodore Rousseau Curatorial Fellow in European Art in the Division of European and American Art, Harvard Art Museums.

Georgina Rayner is the Associate Conservation Scientist in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museums.

Notes

Albert Moore to Frederic R. Leyland, December 22, 1868. Pennell-Whistler Collection, Box 6, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. ↩︎

See for example, James McNeill Whistler, “Mr. Whistler’s Ten O’Clock,” The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924): 135-59; Frederic Leighton, Addresses Delivered to the Students of the Royal Academy: By the Late Lord Leighton (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1896). ↩︎

Robyn Asleson, Albert Moore (London: Phaidon Press, 2000), 7. ↩︎

Henry Moore, quoted in Frank Maclean, Henry Moore R. A. (London, Walter Scott Pub. Co.; New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 119. ↩︎

Sidney Colvin, “English Painters of the Present Day. II—Albert Moore,” Portfolio, 1 (1870): 4. ↩︎

Alfred Lys Baldry, Albert Moore: His Life and Works (London: George Bell & Sons, 1894), 75. ↩︎

Ibid., 51. ↩︎

John Ruskin, “Letter 79,” Fors Clavigera (July 1877), The Works of John Ruskin (vol. 29), ed. E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (London: George Allen, 1907), 160. ↩︎

James McNeill Whistler, quoted in Linda Merrill, A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution, 1992), 144. ↩︎

Merrill, A Pot of Paint, 158. ↩︎

Ibid., 148. ↩︎

See, for example: Robyn Asleson, “Nature and Abstraction in the Aesthetic Development of Albert Moore,” in After the Pre-Raphaelites Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England, ed. Elizabeth Prettejohn (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 115-34; Elizabeth Prettejohn, Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting (New Haven and London: Yale University Press), 101-27. ↩︎

The practice of squaring drawings in order to scale them up was common among Moore’s contemporaries, particularly Frederic Leighton, who not only squared his drawings but also ordered canvases pre-squared from his colourman, Charles Roberson and Co. See: Sally Woodcock, “Leighton and Roberson: An Artist and His Colourman,” The Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1121 (August 1996): 527. ↩︎

Baldry, Albert Moore, 73. ↩︎

Asleson, Albert Moore, 158; Prettejohn, Art for Art’s Sake, 103. ↩︎

Asleson notes that Moore was often in dire financial straits. Early in his career, Moore asked Leyland to advance him £100 several months before he completed his commission of A Venus (1869, York City Art Gallery). See Asleson, Albert Moore, 104. To raise funds at the end of his life, Moore was forced to sell a painting by Whistler, Nocturne: Trafalgar Square – Snow (ca. 1875-77, Freer Gallery of Art) to the Glasgow dealer Alexander Reid. The amount that Moore received for the painting was the subject of much discussion at the close of 1892. See: Moore to Whistler, November 28 and December 5, 1892; Alexander Reid to Whistler, November 25, 1892; and Alexander Reid to Beatrix Whistler, December 2, 1892, The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, 1855-1903, edited by Margaret F. MacDonald, Patricia de Montfort, and Nigel Thorp [online edition, http://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/correspondence]. ↩︎

Moore to Leyland, January 11, 1896. Pennell-Whistler Collection, Box 6, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. ↩︎

Robyn Asleson, “Repetition, Aestheticism, and Copyright Law in the Art Practice of Albert Moore,” in Victorian Artists’ Autograph Replicas: Auras, Aesthetics, Patronage and the Art Market, ed. Julie F. Codell (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2020), 68. ↩︎

Moore to Leyland, December 22, 1868. Pennell-Whistler Collection, Box 6, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. ↩︎

Baldry, Albert Moore, 78. Contemporary scholars have also addressed this dimension of Moore’s practice, see: Richard Green “Albert Moore: Themes and Variations,” in Codell, Victorian Artists’ Autograph Replicas; Asleson, “Repetition, Aestheticism, and Copyright Law in the Art Practice of Albert Moore,” in Codell, Victorian Artists’ Autograph Replicas, 64, 71-73; Asleson, Albert Moore, 130-131, 155-58. ↩︎

Baldry, Albert Moore, 78. ↩︎

The visible crack pattern on Study for “Blossoms” was the reason it was initially brought to the paintings lab for conservation treatment. ↩︎

Rowan Frame, Aestheticism and Painting Method: On Albert Moore and Frederic Leighton, Unpublished Postgraduate Diploma Dissertation (Cambridge: Hamilton Kerr Institute, 2021), 14, 16, 23. Frame’s dissertation also includes a transcription of Albert Moore’s account in the archives of Charles Roberson & Co. The canvases and stretchers that Moore purchased between 1869 to 1893 are listed on pages 65-70. The authors thank Frame for sharing her research. ↩︎

Stephen Hackney, On Canvas: Preserving the Structure of Paintings (Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2020), 26. ↩︎

Richard St John Tyrwhitt, A Handbook on Pictorial Art (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1868), 338. For a discussion of modifications that nineteenth-century British artists made to commercially primed canvases see: Maartje Stols-Witlox, A Perfect Ground: Preparatory Layers for Oil Paintings 1550-1900 (London: Archetypes Publications, 2017), 146-47; Joyce H. Townsend, Jacqueline Ridge, and Stephen Hackney, Pre-Raphaelite Painting Techniques, 1848-56 (London: Tate, 2004), 56-59, 80-81. ↩︎

Identified with X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy analysis as vermilion, cobalt blue and cadmium yellow, respectively. ↩︎

For a discussion of the presence of such borders on a selection of Moore’s other oil studies, see Frame, Aestheticism and Painting Method, 16-17. ↩︎

Baldry, Albert Moore, 78. ↩︎

The presence of umber can be inferred due to an increased amount of manganese in comparison to iron detected by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy. ↩︎

The presence of madder may be suggested based on the orange fluorescent particles observed in cross-section. The presence of other organic reds cannot be ruled out from this analysis. ↩︎

Email correspondence (October 6, 2020) with Tate staff: Amy Griffin, Paintings Conservator; Bronwyn Ormsby, Principal Conservation Scientist; and Joyce Townsend, Senior Conservation Scientist. ↩︎

Baldry, Albert Moore, 76. ↩︎

For discussions of the role of seriality in Moore’s oeuvre and working process see: Asleson, “Repetition, Aestheticism, and Copyright Law in the Art Practice of Albert Moore,” and Green “Albert Moore: Themes and Variations,” 55-76. ↩︎

Baldry, Albert Moore, 52. ↩︎