Technical Analysis and Treatment of a Siberian Reindeer-Fur Overcoat

Annabelle Camp

Introduction

During the 2020–21 academic year, a child’s hooded overcoat from the Dolgan (tiajono)1 peoples of Siberia served as a student treatment project at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. The coat consists of animal skin, with fur intact, and fulled2 wool with beadwork (Fig. 1). It measures 96.5 cm across with arms outstretched and 73.7 cm from the top of the hood to the bottom of the coat body. It arrived on loan from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in poor condition, due in large part to a past moth infestation. In tandem with the extensive treatment, technical analysis was conducted at the Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory (SRAL) at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Analysis included polarized light microscopy (PLM), x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), pH testing, collagen shrinkage temperature testing, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and peptide-mass fingerprinting (PMF) using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. Each analysis provided valuable information regarding the coat’s original context and current condition.

The overcoat was collected by University of Pennsylvania Museum ethnologist Henry Usher Hall and Polish anthropologist Maria Czaplicka during their eighteen-month expedition in 1914 and 1915 down the Yenisei River in Siberia.3 The two Oxford-trained anthropologists surveyed and gathered materials not only from the Dolgan, but from numerous other tribes of the northeastern Siberian tundra.4 At the time of this expedition, Westerners knew little about these groups, although explorers and traders from Russia had been in contact with peoples of the region since the early eighteenth century.5

The lifeways and material culture of the Dolgan peoples resemble much of that of neighboring tribes, such as the Yakut, Evenk, and Nenet.6 Very little English-language scholarship specifically about Dolgan material culture has been published. However, this coat is distinctively Dolgan in style, allowing for a confident attribution. As James Forsyth notes, “the most characteristic Tungus [Evenki] feature of all Dolgan garments—in contrast with the rather plain clothing of the northern Yakuts—[is] its colorful decoration with strips and geometric designs made of cloth applique and glass beads,”7 as present on this coat. Additionally, the Dolgan peoples adopted a hooded pullover style similar to those worn by the Nenet,8 also demonstrated in this piece.

It is a traditional child’s winter overcoat comprised primarily of skin, estimated to be reindeer upon initial inspection, with fur intact. The coat has long sleeves, and when worn the bottom hem would likely hit slightly above the ankles. The main body of the overcoat, which is a pullover style with a V at the neck, consists of two pieces of fur with seams along the sides and shoulders (Fig. 2). Along the bottom there is a red fulled-wool strip decorated with beadwork followed by a fur strip. Each sleeve consists of two pieces of fur, separated by a red fulled-wool beaded strip. These wrap around the arm and are seamed along the underarm. The hood consists of eight pieces of skin with fur intact. Two separate strips of fur are stitched along the interior of the hood opening to create a fur edging and lining. The fur used for the edging is visually different from that used for the body of the coat. The hood additionally has skin ties, one on either side of the opening, and is decorated with red fulled wool covered almost entirely with colored glass seed beads. There are also two tassels of red and blue wool strips on either side of the hood. All of the flat seams are sewn using sinew, while the beadwork appears to have been sewn using both a plant fiber thread and sinew. Such coats would have typically been layered over inner garments with hair on the interior to improve insulation.

Fur Components

The fur used for the body of the coat and lining of the hood is dense and primarily brown, with some areas of lighter pigmentation along the shoulders. There were strong suggestions that the fur is reindeer, including cultural context and the extensive hair slippage that is characteristic of deer hair due to its hollow shaft. For all native groups of this region, now designated by Russia as the Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetskii District and encompassing over 53,000 square km,9 reindeer have historically been an essential part of everyday life. As Marie Antoinette Czaplicka notes in her account from the expedition, the groups are nomadic “reindeer breeders, hunters, and fishermen who live in reindeer skin tents” called chum.10 The animal continues to be key to the sustenance, social organization, and material culture of the Dolgan peoples. The movements of the groups are dependent upon finding fields of moss where their herds can graze. Reindeer skin11 is used for dwelling coverings as well as garments like this child’s coat. It is an essential clothing material in the arctic environment, because it provides sufficient insulation to maintain heat, while it is breathable enough to prevent sweat from freezing on the wearer’s skin.12 Skin processing and subsequent garment construction is primarily a woman’s activity, with knowledge passed down through generations.13 In the Siberian arctic and subarctic, reindeer are typically slaughtered around September, and skins may be frozen prior to drying, scraping, and tanning.14 Children’s clothing like this coat is typically made from reindeer calf skin, which is thinner and softer.15 Irregularities and holes in the skin, such as those caused by warble flies, would have been patched during manufacture. Three such repairs are present on this coat.

In addition to the fur used for the body of the coat, the fur edging of the hood, which measures approximately 1.0 cm wide and is a reddish brown, has longer, coarser guard hairs, suggesting it may have come from a different part of the animal or from a different animal entirely (Fig. 3). Hoods similar to those of the Dolgan peoples have linings of wolverine fur,16 which is a common fur type used in parkas because it will not hold frost.17 However, lynx, dog, marmot, pine martin, ermine, mink, and sable furs are also used for decorative elements.18

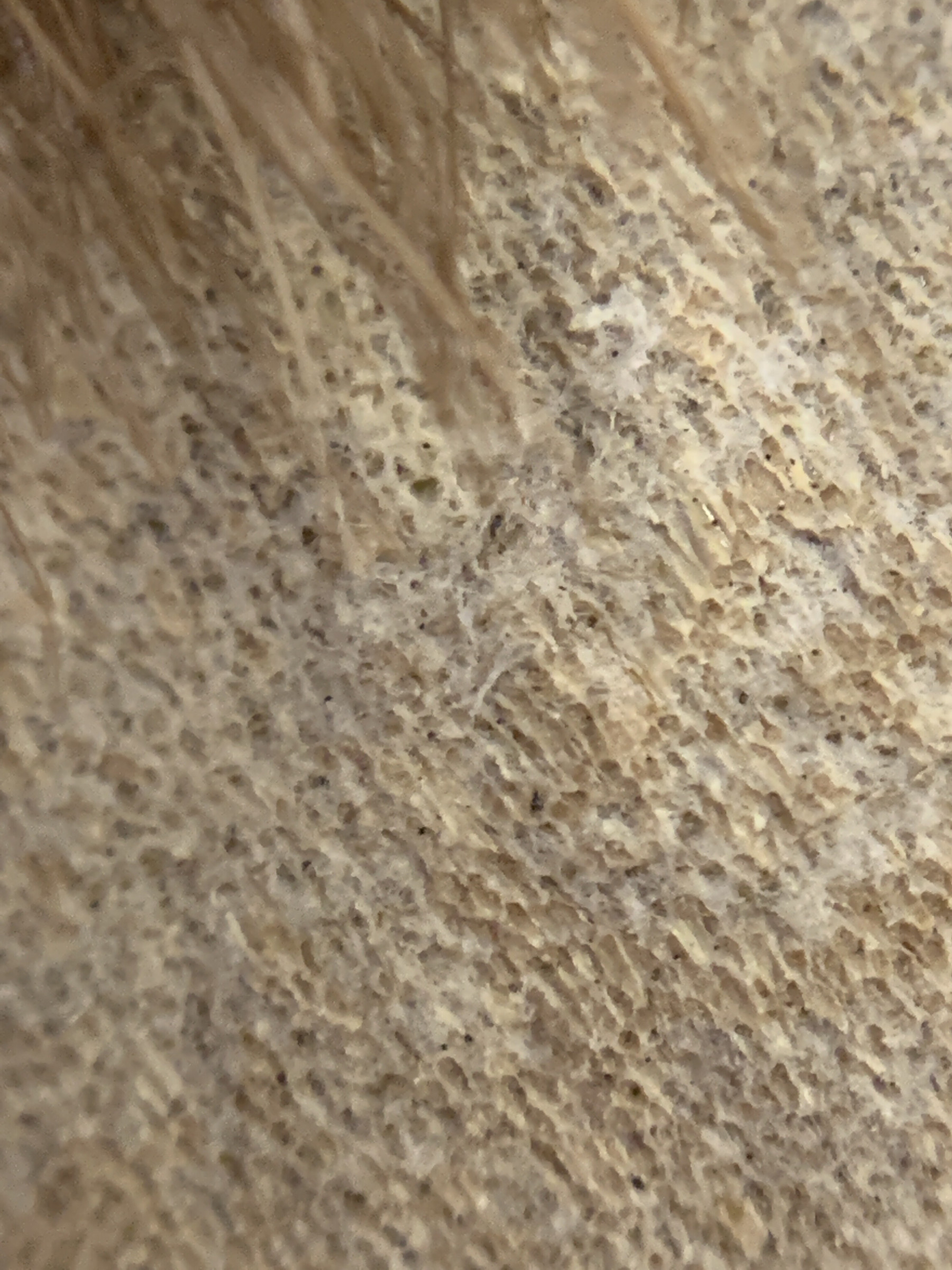

To confirm the species, the skins and fur were examined using nondestructive examination techniques followed by destructive analyses. Both fur types were examined using longwave ultraviolet (UV) illumination and demonstrated the typical bluish-white fluorescence of keratinaceous materials where not masked by melanin pigments. Follicle patterns were examined using high magnification in areas where the skin was visible. Due to extensive grazing from webbing clothes moths, subtle differences that would be visible in a fully intact grain layer were indiscernible, though both could be described as dense (Fig. 4). Thus, it was deemed necessary to conduct PLM of the hairs from both skin types (Table 1).

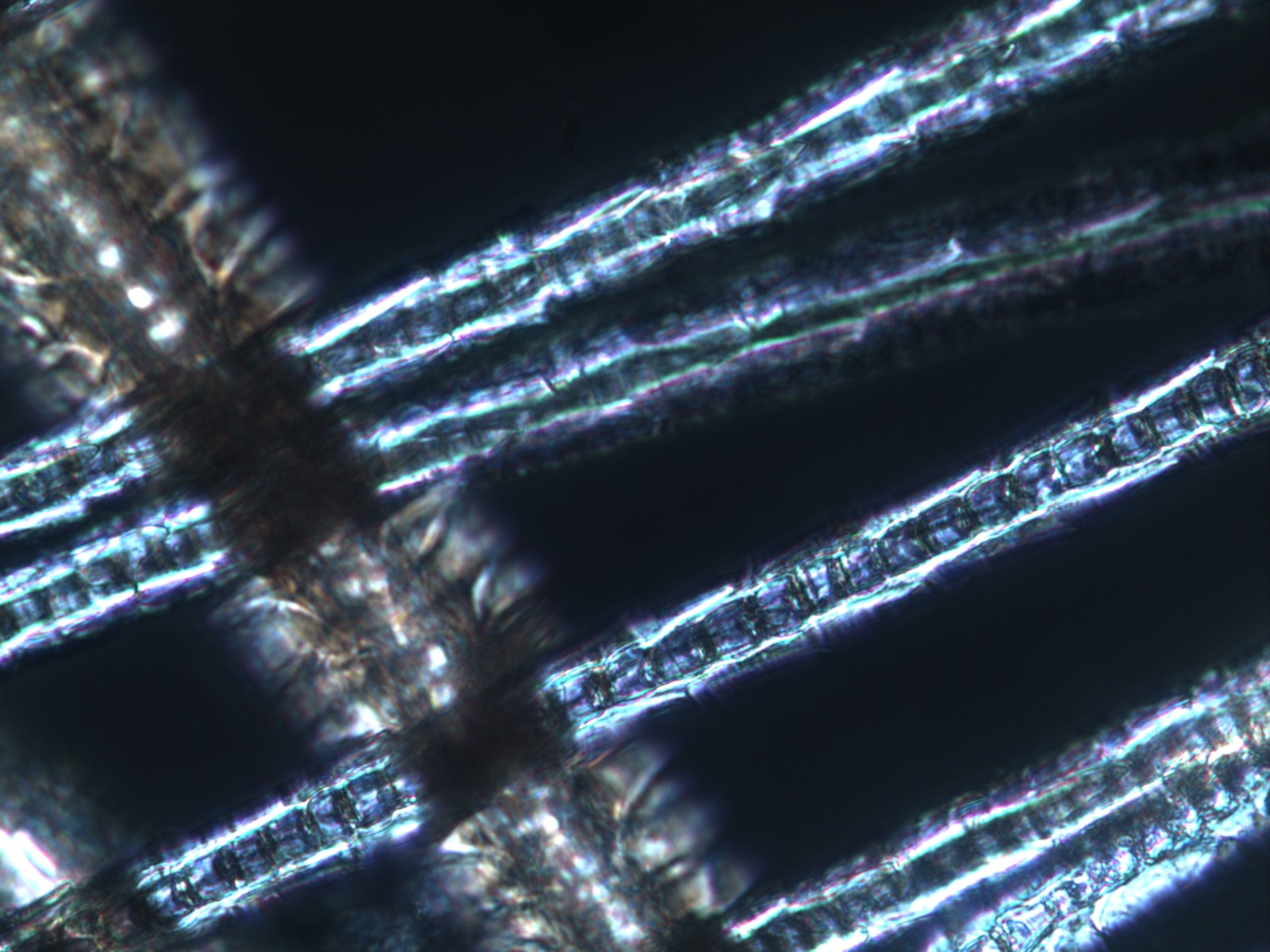

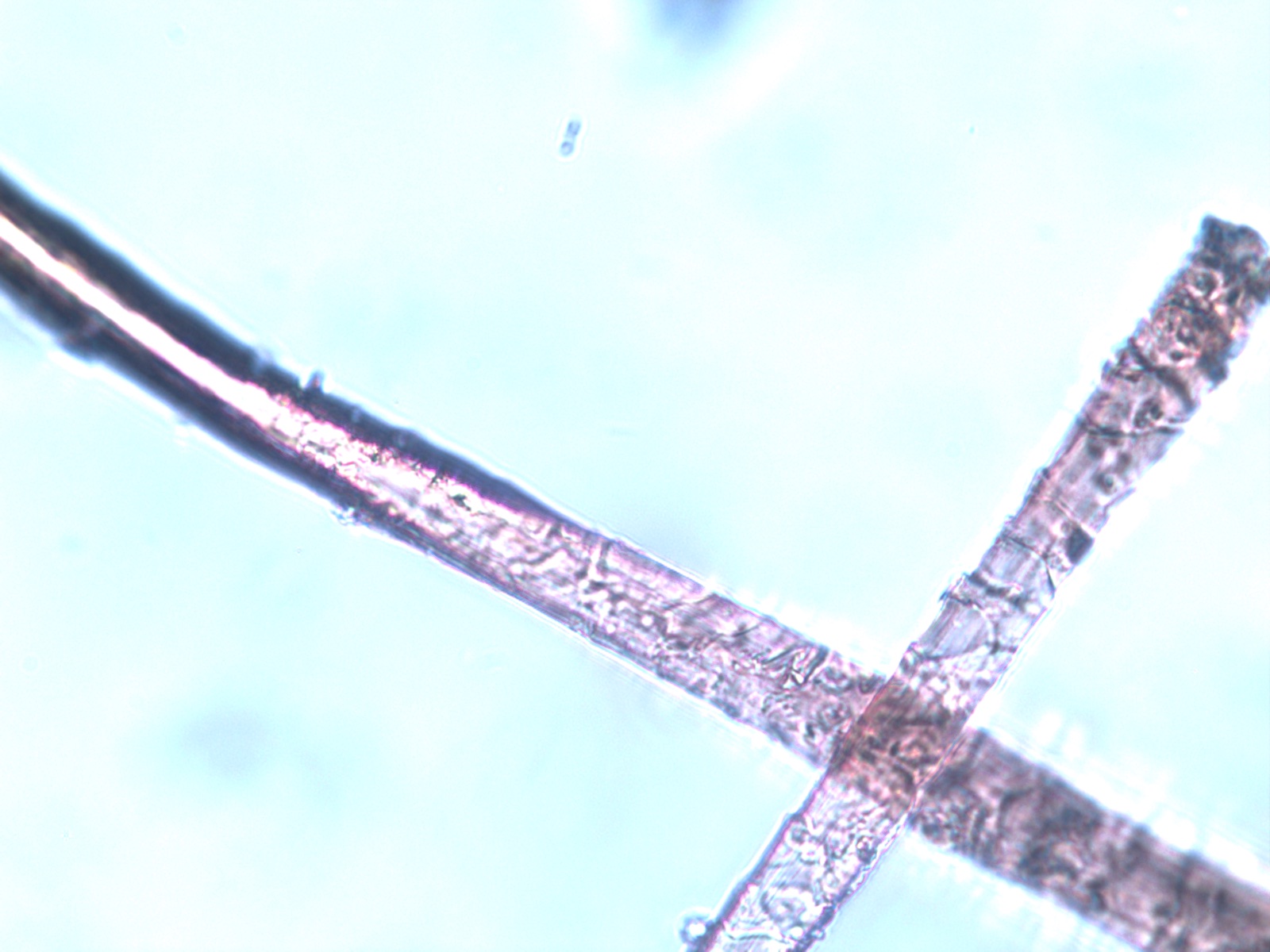

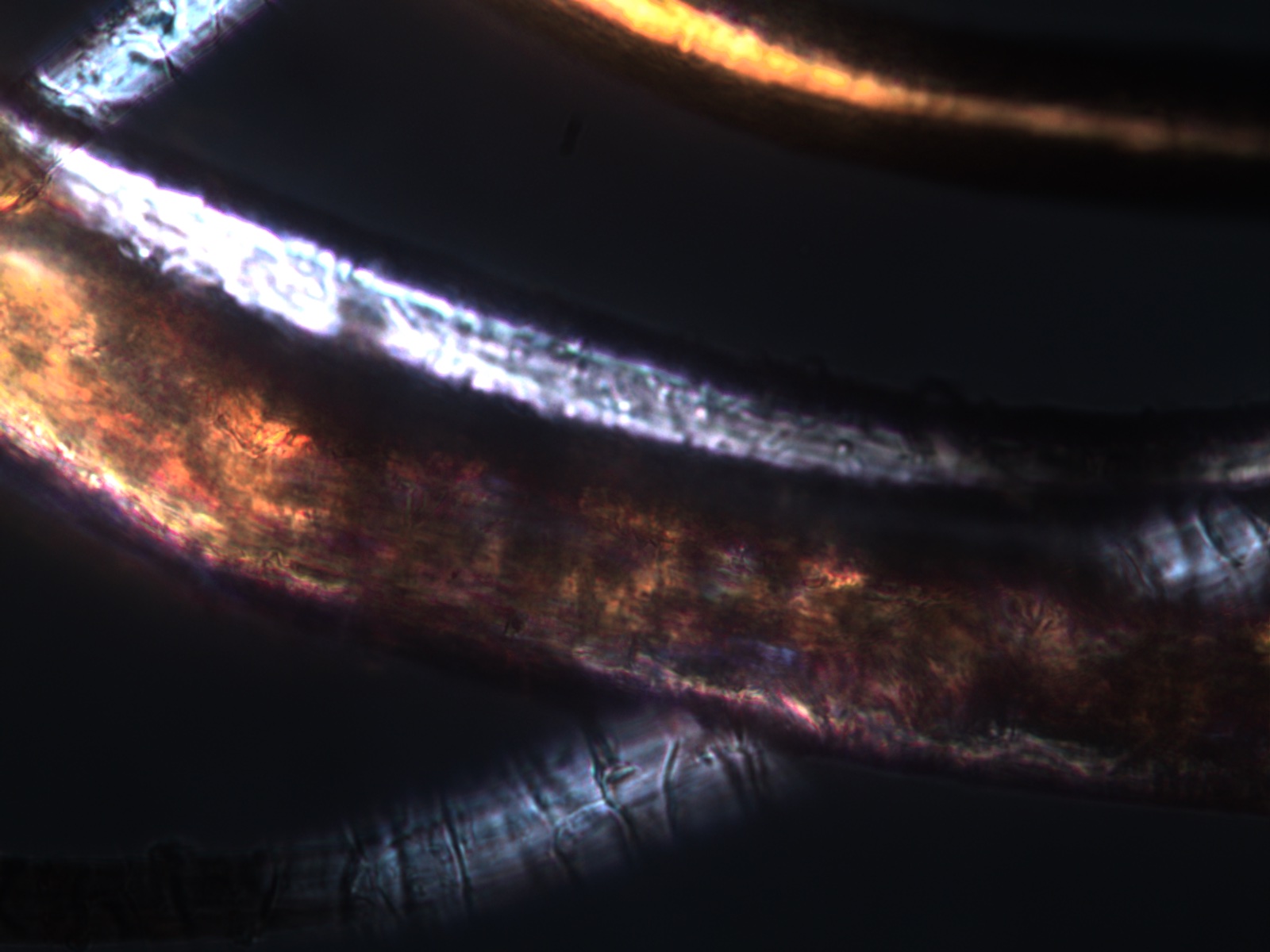

Table 1. Polarized light microscopy19

| Sample location | Normal light | Polarized light |

|---|---|---|

| Hair from primary skin of coat | ||

| Hair from edging of hood | ||

| Bottom textile band |

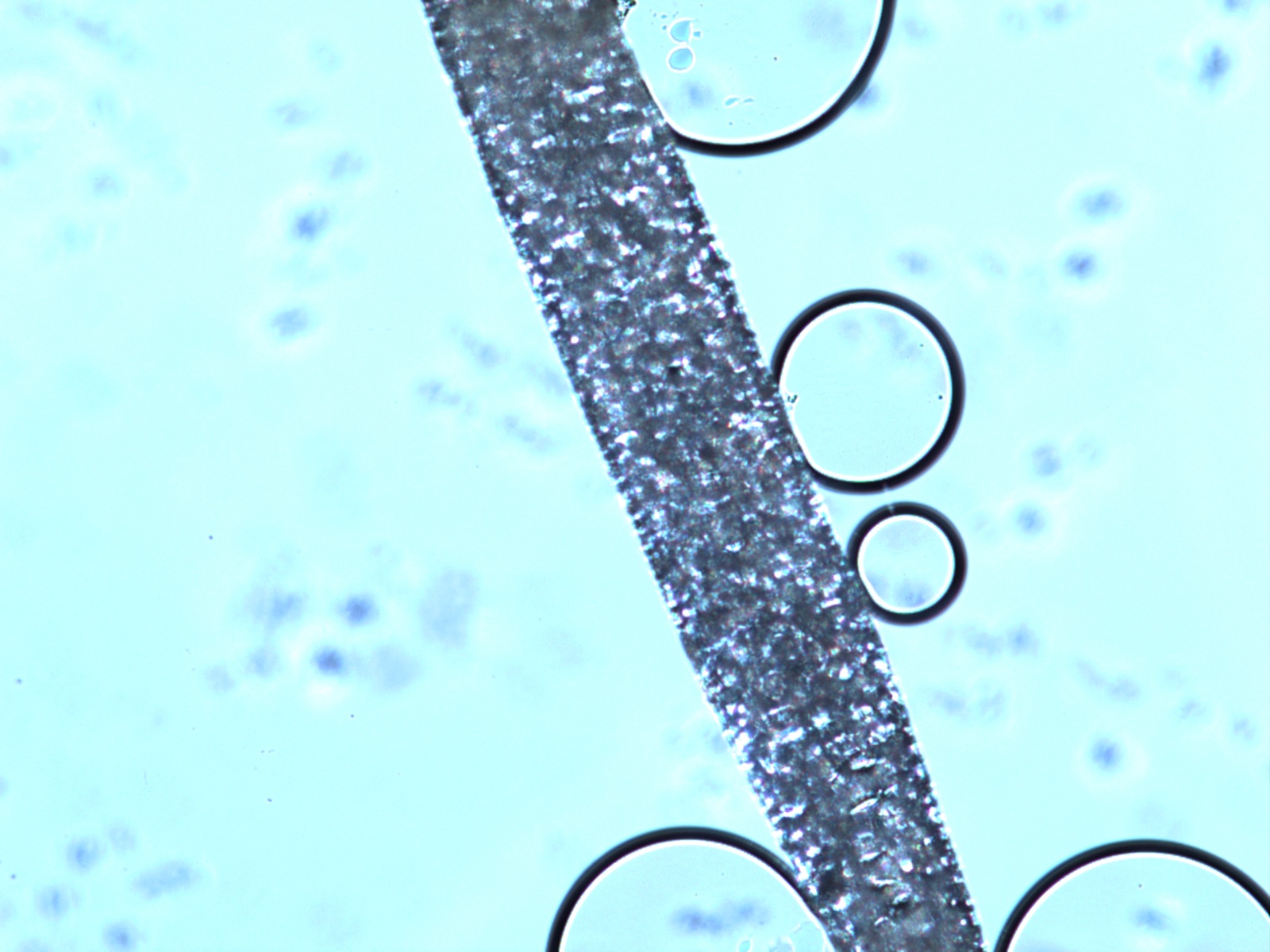

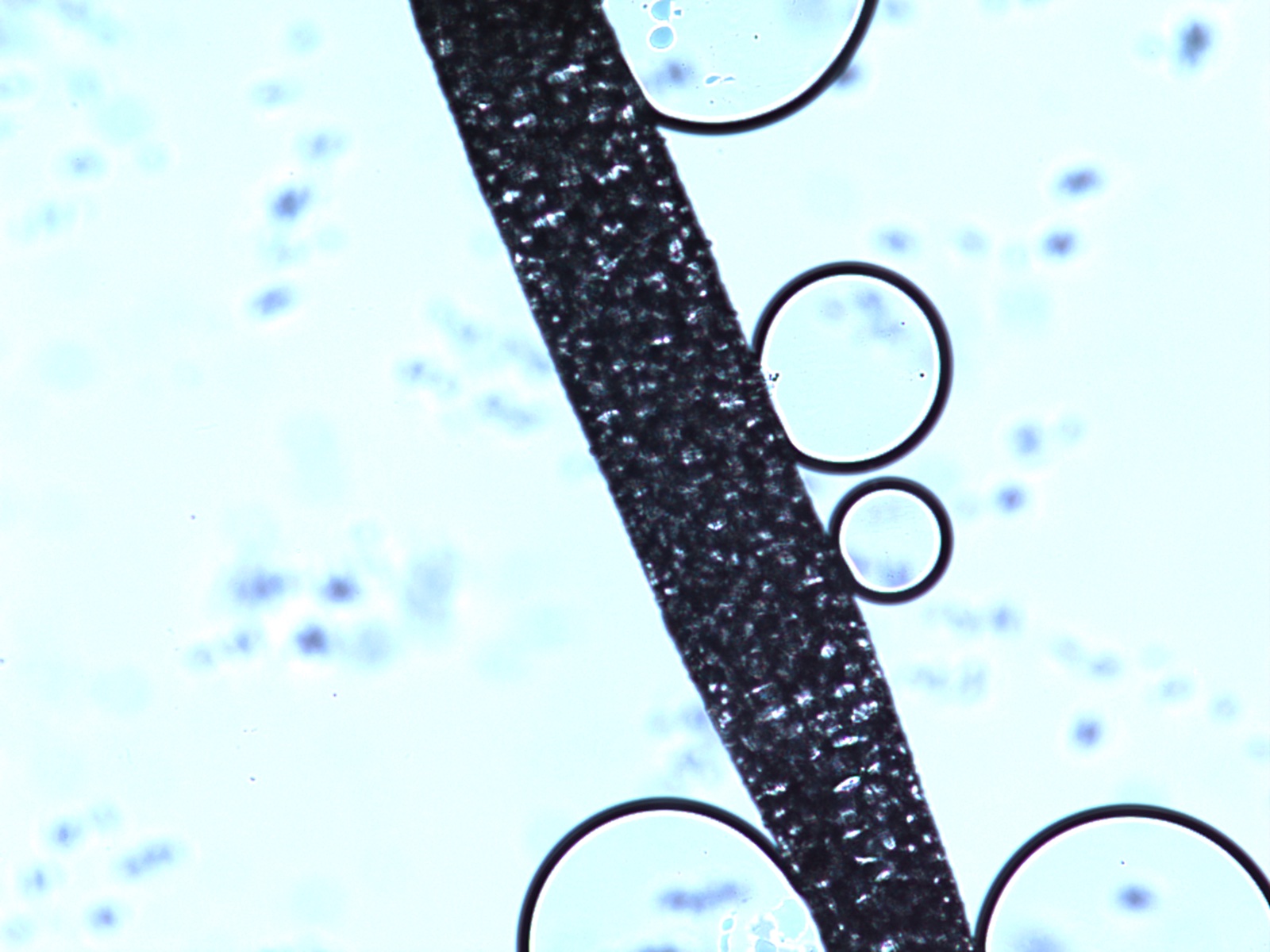

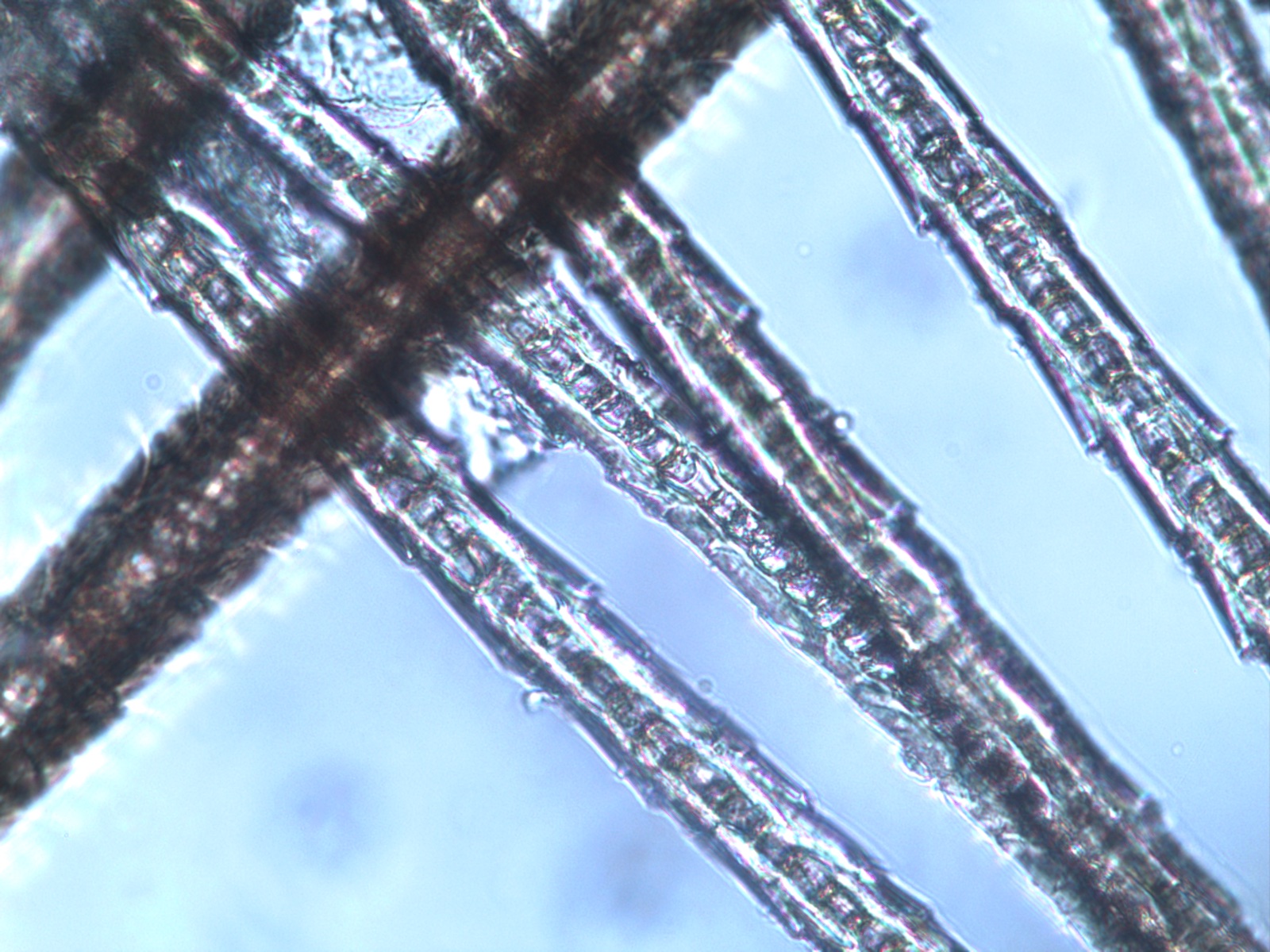

Hairs from the primary skin of the coat had small honeycomb-like scales resembling deer, while the hair from the hood edging had interrupted medullary scales, resembling dog or wolverine. This confirmed that the two furs were not from the same species.

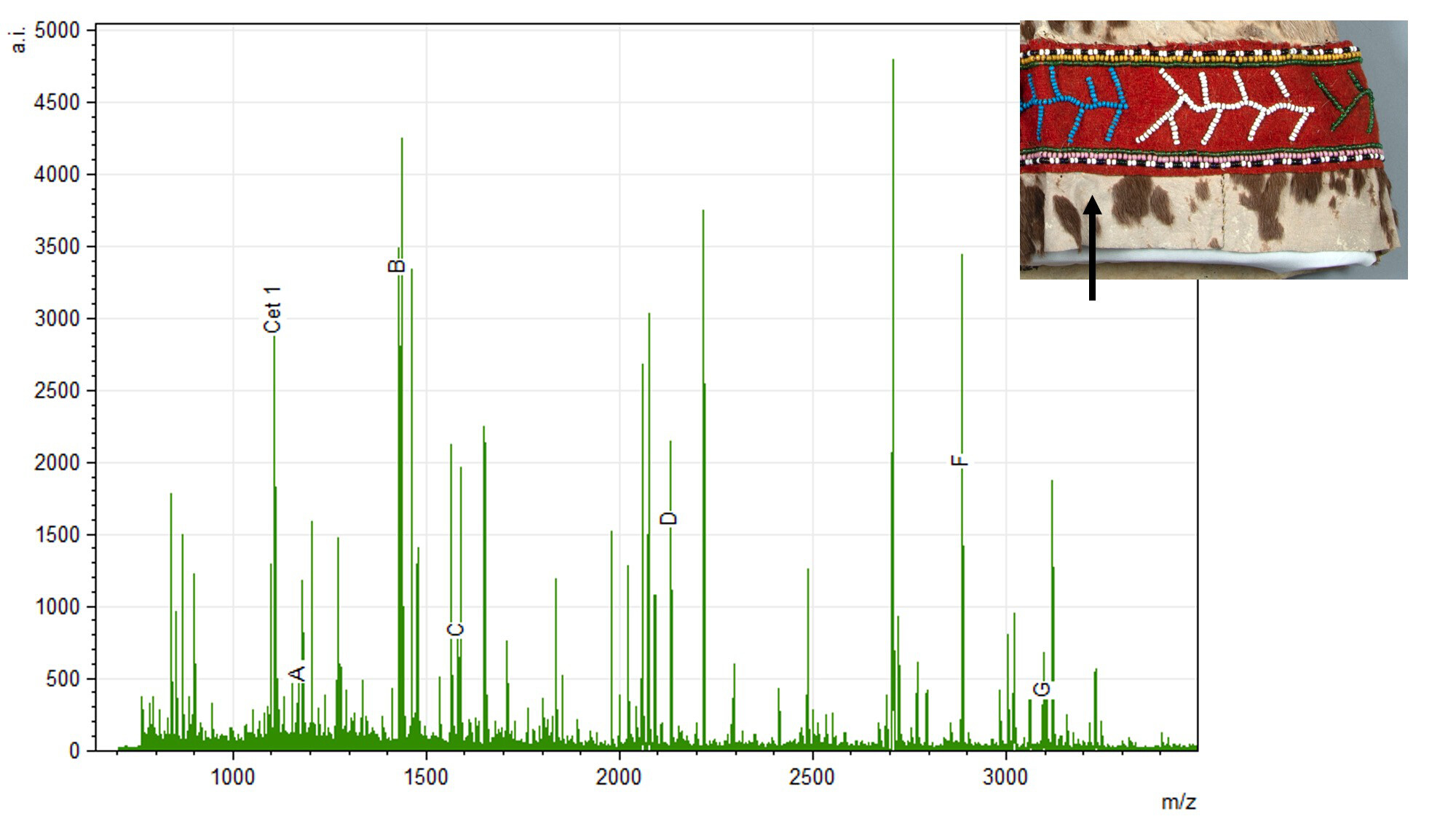

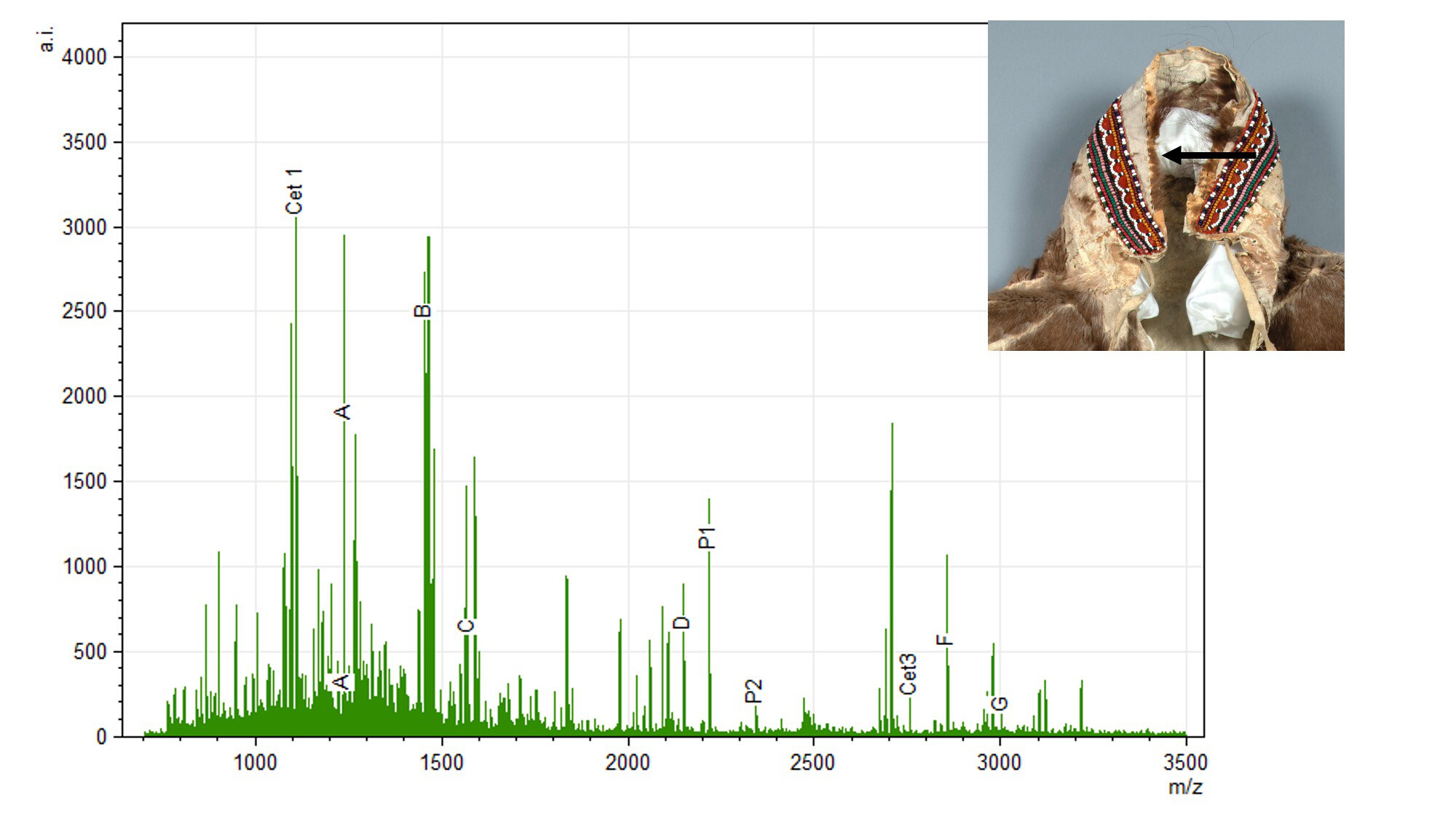

Dog and wolverine are both possibilities on coats from this region and period. Thus, to further establish the species identification, particularly for the fur edging, PMF using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was conducted on collagen samples from both skin types.20 The samples taken from the body of the coat had excellent agreement with the reference markers for reindeer collagen, showing all but one: Cet1 (1105), A (1166), B (1428), C (1580), D (2131), F (2883), and G (3093) (Fig. 5). This is consistent with the PLM results, condition issues, and cultural context for the estimation of reindeer.

Results from the samples taken from the hood were compared with collagen reference markers for dog and wolverine. It did not match well with dog. However, it consistently matched reference markers for wolverine: Cet1 (1105), A (1235), B (1453), C (1566), D (2147), P1 (2216), P2 (2342), Cet3(2753), F(2853), and G(2999) (Fig. 6). Therefore, the skin is believed to be wolverine. This is consistent with the PLM results and cultural context and further clarifies the PLM results.

In addition to identifying the species, it was necessary to understand the tanning method and extent of deterioration of the skin prior to carrying out certain treatment steps, such as humidification and tear repair. The flesh side of the reindeer skin is pale white and soft, suggestive of a brain-tanning method. The flesh side of the wolverine skin on the hood, however, has an orange cast, possibly due to the difference in species or a difference in tanning method. It is known that the Evenk people of Siberia smoked their skins using white rotted wood, moss, damp wood, or a combination of these to impart water repellence and color to the skin.21 It is likely that the Dolgan peoples had methods similar to those of the Evenk, due to their geographic proximity. While FTIR can be conducted to detect tanning processes and the applications of fats or water-repellent materials such as cod liver oil or bone marrow, which was also used by the Evenk,22 this level of analysis was not deemed necessary to inform treatment. However, obtaining collagen shrinkage temperatures (Ts) of skin samples from numerous locations on both the hood and the body of the coat was crucial to further understand the skins’ condition.

Table 2: Collagen shrinkage data (all values are in °C)

| Sample | A1 | B1 | C | B2 | A2 | TI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body sample 1, run 1 | 29 | 34 | 38 | 49 | 52 | 62+ |

| Body sample 1, run 2 | 32 | 35 | 38 | 51 | 53 | 63+ |

| Body sample 2, run 1 | 29 | 35 | 41 | 51 | 54 | 65+ |

| Body sample 2, run 2 | 31 | 35 | 37 | 49 | 51 | 65+ |

| Hood edging | 31 | 35 | 37 | 49 | 52 | 65+ |

The temperatures outlined in table 2 are defined as follows: A1= the temperature at which individual fibers shrink sporadically; B1 = shrinkage in one fiber followed immediately by shrinkage in another; C = two or more fibers shrink continuously at the same time, followed by the shrinkage of a mass of fibers. The temperature at which this begins is Ts; for B2, see B1; for A2, see A1. TI = the temperature where all movement/shrinkage ceases.

The tests, outlined in table 2, should have been raised to a higher temperature to meet current testing protocols. However, Ts values, which correspond to C in table 2, were determined for both skin types, and they were consistent with degraded brain-tanned skins. The published Ts value for brain-tanned skins is approximately 65°C, and the Ts values for both skins are well below this point, suggesting that they are in poor condition despite their flexibility. This meant that the coat could not undergo any heat treatments, such as the use of a heat-reactivated adhesive for tear repair. However, because the Ts values for all samples were safely above room temperature, humidification was deemed safe if done with due care, following local testing to determine the object’s sensitivity to moisture.

While the confirmation of brain-tanned reindeer skin with wolverine hood edging was unsurprising, it further supports the significance of this coat as an example of traditional Dolgan clothing. At the time of this coat’s acquisition in 1915, the Dolgan peoples’ interactions with non-native peoples was primarily limited to tribute-collecting representatives of the Russian czar and fur trappers.23 Soon after, however, they experienced forced service during the Russian Civil War and subsequent collectivization.24 During the Soviet era, many native Siberians, including the Dolgans, were forced to abandon their nomadic lifestyle as well as their reindeer. While peoples of this region continue to hunt reindeer seasonally, even this has been threatened by industry in the region and by climate change.25 Thus this coat is an example of a piece produced by a culture on the brink of lasting change.

Fulled Wool

The coat is decorated in multiple areas using strips of plain weave, fulled red wool with applied beadwork. The fibers were examined using PLM and demonstrated the scale pattern associated with sheep’s wool (Table 1). The textile fibers have a Z-twist. There are strips on the bottom and on each sleeve, all of which have a thread count of 6 × 8 threads per cm (warp vs. weft). The hood has numerous textile elements. A thin strip encircles the opening; this strip has a denser weave than the wool on the sleeves and along the bottom, and is a more orange tone than the other textile elements. On the back of the hood there are three additional textile components: a point in the center and an arc on either side. There are also two oval segments placed symmetrically on the back of the hood, directly above two tassel-like bundles of textile strips (Fig. 7).26 These strips, unlike all other textile decorations on the coat, are not beaded, and consist of blue and red fulled wool.

All of the textile decorations are pieced elements attached via flat seams to the surrounding skin using sinew whipstitches. The bottom strip consists of one piece, with a side seam on the proper right. This suggests that the main body was constructed of fur, with seams down each side. The textile strip would have then been attached, followed by the bottom fur strip. On each sleeve, the seam on the textile strips corresponds to those on the sleeve overall, suggesting that all three segments were stitched together prior to seaming the entire sleeve. The hood consists of many fragments of skin sewn around the textile pieces, suggesting that the fur elements were constructed around or in tandem with the textile components.

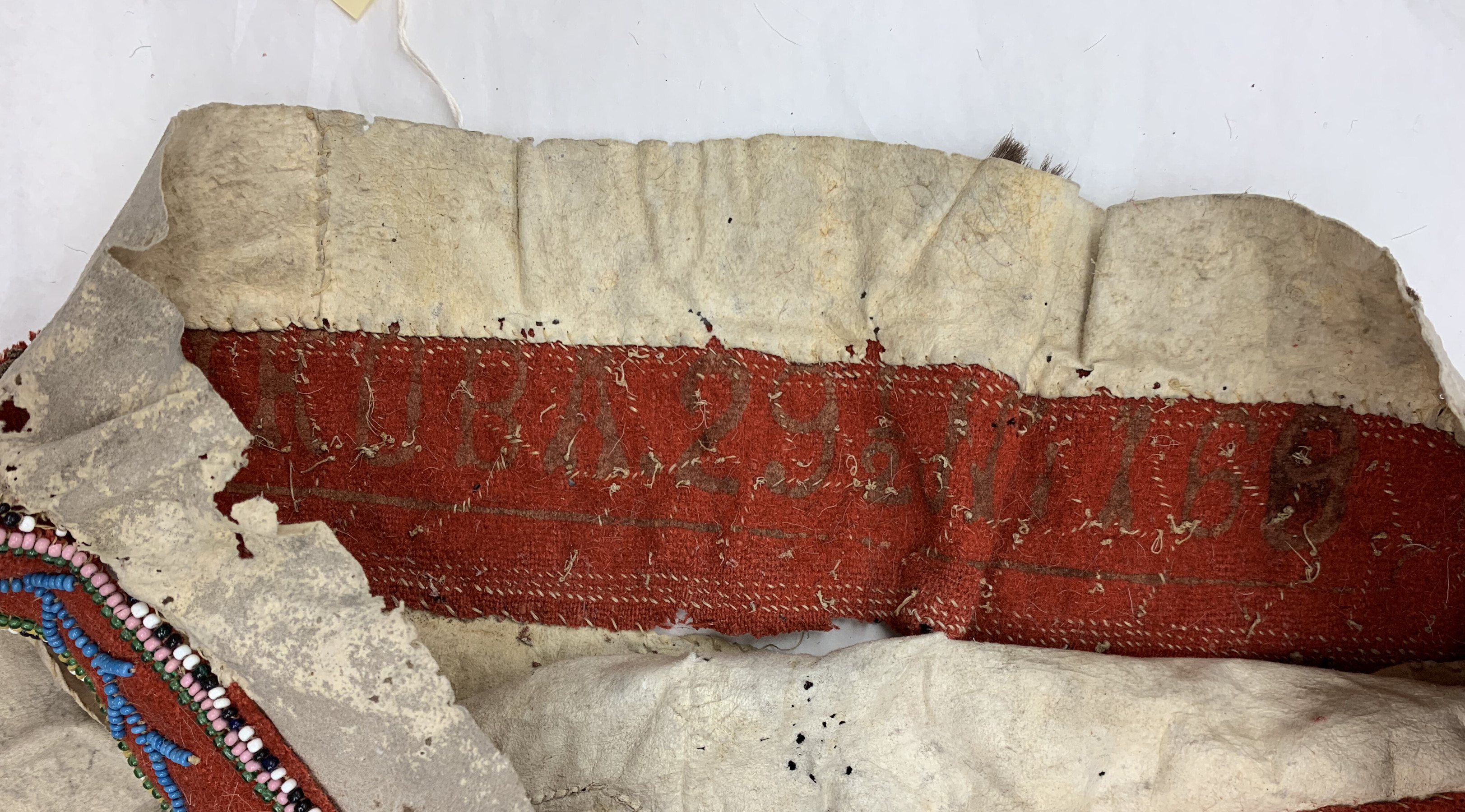

The asymmetrical piecing of the hood suggests that the maker utilized scraps or was reusing elements of other garments in this coat’s construction. This was confirmed during treatment; a stamp on the interior of the fulled wool at the bottom of the coat was discovered, reading “ушкова.29 ½ н 169” (Fig. 8). Vera Solovyeva, an associate at the American Museum of Natural History, translated the Cyrillic as “Ushkov” and explained that the piece was cut from a textile, likely a sack, either used or manufactured by one of the Ushkov Company’s plants.27 As the thread count, material, and color of the strips on the coat sleeves match those of the stamped strip, it is likely that they were cut from the same textile.

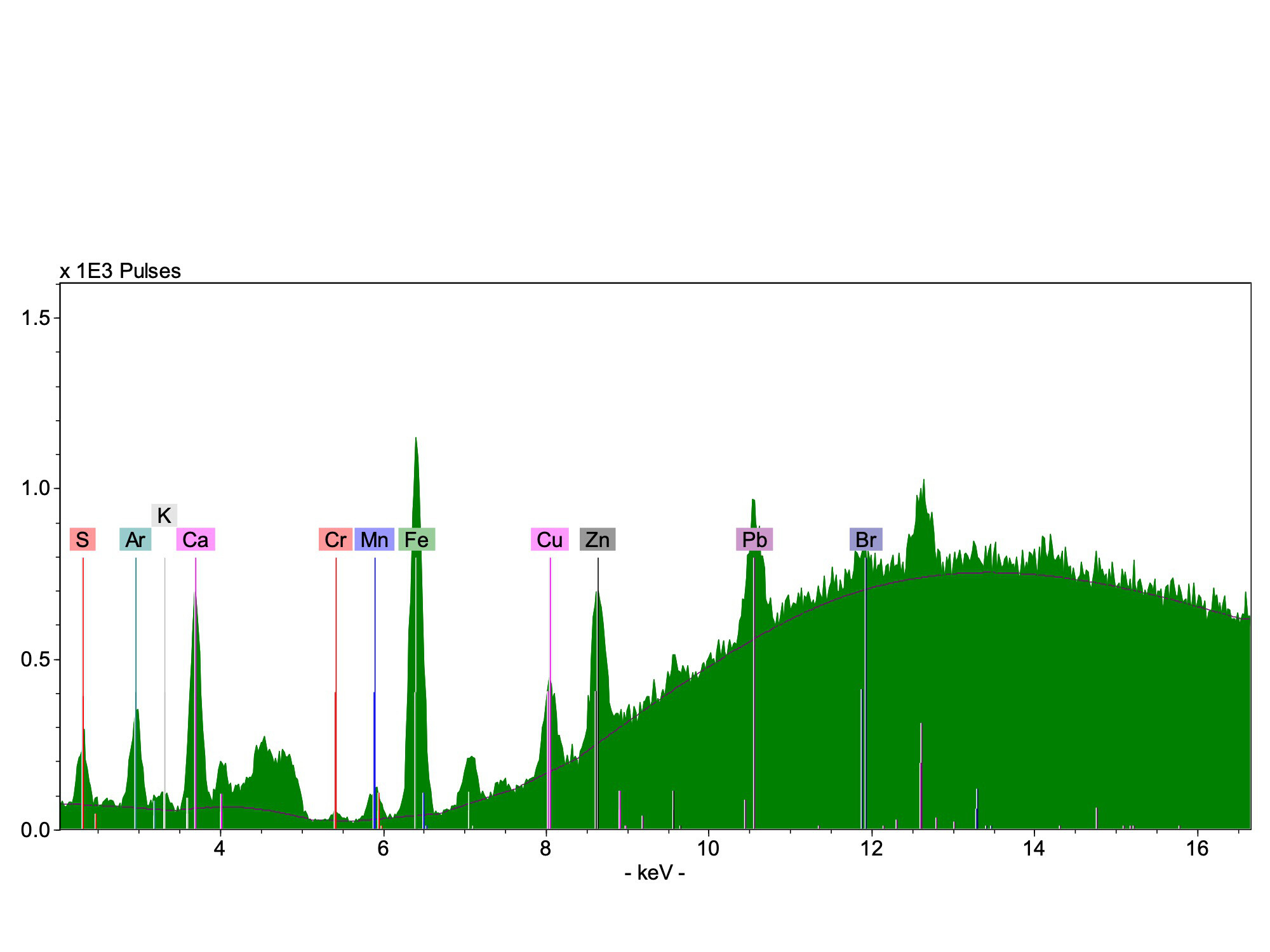

The Ushkov Company was established by Kapiton Yakovlevick Ushkov in Tartarstan, a region of Russia with a rich history of chemical production. The Ushkov Company produced a variety of chemicals in the Russian Empire but was established for the manufacture of potassium bichromate, a common textile mordant. During initial examination of the coat using XRF in both the fur and wool components, only elements commonly associated with pesticides were noted. However, upon the discovery of the Ushkov stamp, the results were reexamined, and a small chromium x-ray line, possibly due to a potassium bichromate mordant, was detected in areas of wool tested (Fig. 9). The limited sources available suggest that the Ushkov Company was founded in 1868 and was renamed the Karpov Chemical Company in 1880. This suggests that the textile was either manufactured or used by the company during those twelve years. However, due to the recycled nature of this component, it can only be stated that the coat was made after 1868. Further research into the company’s history is recommended.

Glass Beadwork

As discussed above, all of the red wool elements, excluding the tassels on the hood, are decorated with glass seed beads, which indigenous groups in the arctic have obtained for millenia as part of extensive trade networks. On this coat, the beads have been primarily attached using sinew. However, portions of beading on the hood appear to have been attached using a hand-spun plant-fiber thread. This is distinguished from the fine sinew used for the other beading, because it is softer and has an S-twist. The beading has been completed by couching strands of beads to the textile. Couching stitches are placed between every bead.

There are four beadwork patterns utilizing fourteen different colors of beads. The bottom strip has three rows of beads on each edge. Running horizontally through the center are nine branch- or leaflike designs (Fig. 10). The textile components on the sleeves have two rows of beads on either side, with a leaf- or vinelike design in the middle. This design primarily consists of two rows of beads running down the center with oval shapes that include an outline of one color filled with two to four beads of another color arrayed to either side of this central line. This design is not symmetrical and utilizes eight different colors of beads in no discernible pattern. Additionally, the pattern on the back of the left sleeve is different (Fig. 11). While it utilizes the same colors, there is not one central stem but instead multiple interlocking stems, with one leaf curling off of another. This may suggest that this coat was beaded by more than one individual.

The textile elements on the hood have the most concentrated beadwork. The strip that encircles the opening is decorated with four rows of beads on the front edge and five rows on the back edge. Between these linear rows of beads is a simple scalloped design consisting of one row of opaque white beads punctuated with black beads. This design, common to Dolgan beadwork in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, is found on a number of objects from this period in the collections of Moscow’s Kunstkamera, the Russian Ethnography Museum (St. Petersburg), and the Bata Shoe Museum (Toronto).28 The five other pieced wool elements on the hood are covered entirely with rows of beading in different colors. The beadwork is symmetrical on either side of the hood.

Testing of the beads themselves was minimal, as they posed the fewest condition issues. When examined using long-wave UV illumination, no differences in fluorescence among the various colors were observed. However, many colors demonstrated varying levels of pitting that was suspected to be a sign of glass disease (Fig. 12). To confirm this and to guide cleaning protocols, the surface pH was tested using Hydrion pH strips. Each bead color was tested at least once, and beads on all major areas (sleeves, bottom strip, and hood) were tested. In all test locations, areas of pitting were alkaline (pH 11–13), confirming the presence of glass disease.

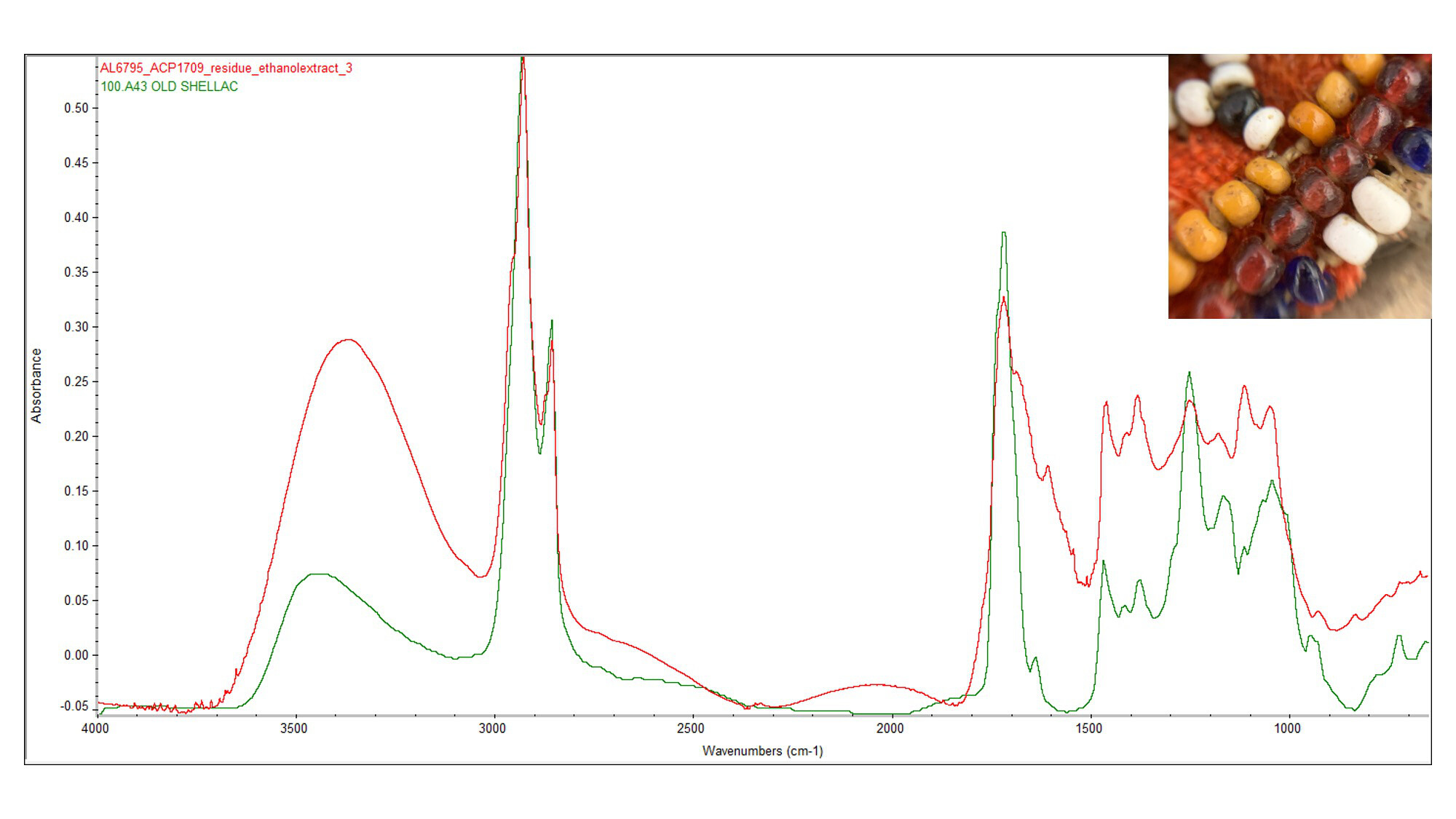

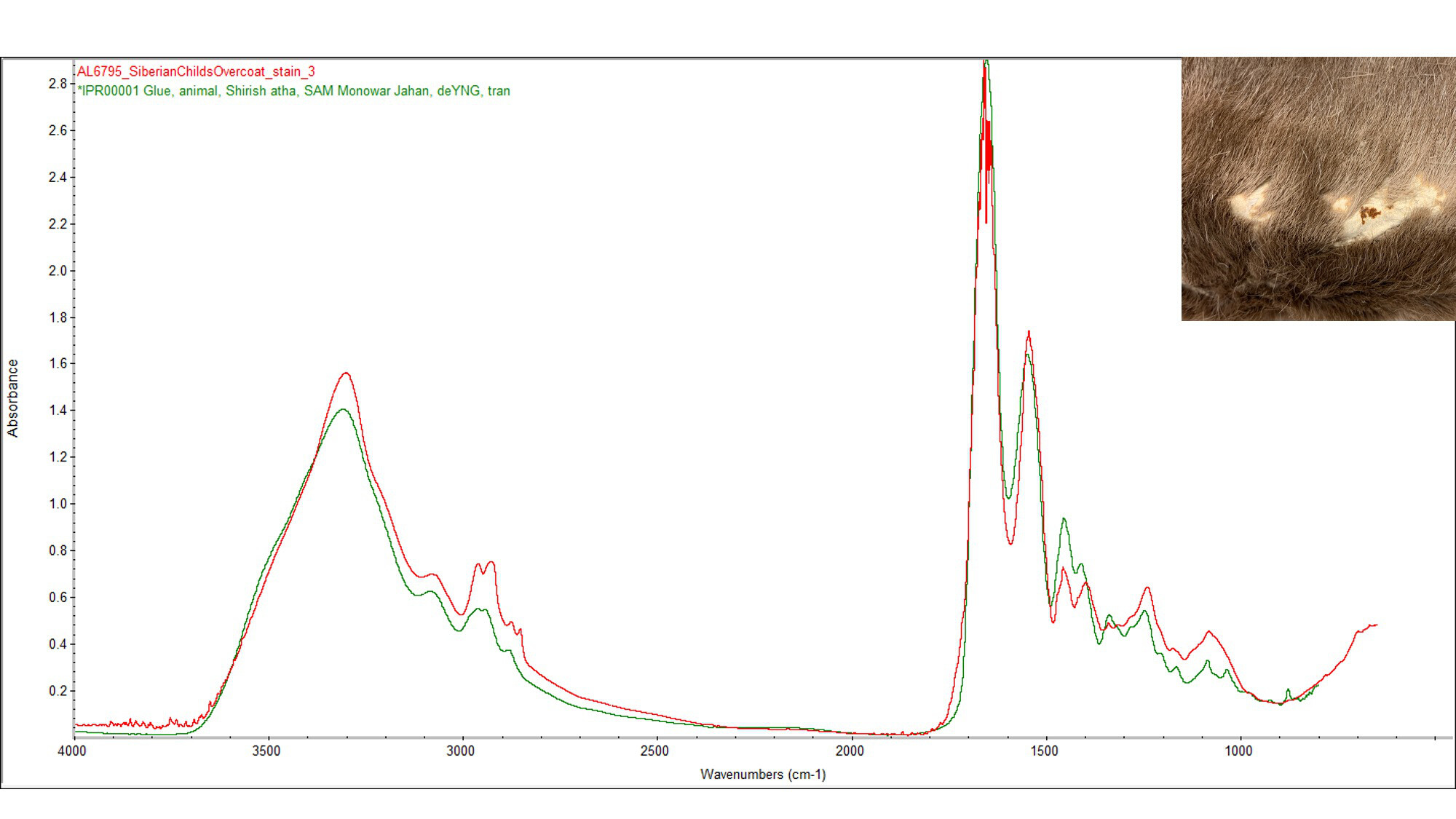

Additionally, during cleaning a brown residue was found scattered on the beading on the hood (Fig. 13). Because this material may be evidence of use, it was examined, along with an area of red-brown staining on the skin of the coat (Fig. 14), using FTIR (Figs. 15, 16). The stain on the body of the coat was found to be proteinaceous, while the residue on the beads was found to be resinous. Based on these results, which could provide further information on the environment in which the coat was worn, the residues and staining were left intact.

Treatment Summary

Much of the analysis presented here was done in tandem with conservation treatment. Overall, the coat was in poor condition. It was covered in surface grime as well as moth casings and frass and loose hairs. There are losses to the fur due to the inactive moth infestation and the natural slippage inherent to reindeer fur. In some areas, moth grazing was so extreme that it has resulted in holes and thinned areas in the skin. There were also large tears in the seams along the bottom where the wool was consumed, resulting in failure of the stitching. All of these factors, as well as creases and distortions in the skin due to prolonged flat storage, meant the coat could not be safely handled without causing further damage. Additionally, numerous beads were broken or loose and thus at risk of loss.

Treatment of the coat was completed while wearing appropriate personal protection equipment due to the presence of lead and bromine detected via XRF, and appropriate handling guidelines are now included in its housing. Between the coat’s collection in 1914–15 and implementation of integrated pest management in 1981, the University of Pennsylvania Museum made numerous efforts to combat pest infestation, including the use of leaded gasoline (early twentieth century), paradichlorobenzene (before 1971), methyl bromide (1971), and ethylene oxide (1971). The bromine detected via XRF suggests this coat was treated with methyl bromine. The lead may suggest the coat was treated with leaded gasoline. However, no smell was present, and when tested with Plumbtesmo® lead test paper, no lead was detected. This suggests the concentration of lead on the coat was minimal. Additionally, the extent of moth damage suggests the pesticide was likely applied after infestation had occurred.

Treatment included extensive vacuuming and removal of moth casings and frass. The coat was fully vacuumed three times during treatment, as more frass and detached hairs were shed. The exposed skin and beads were further cleaned by vacuuming through Vellux.29 Due to the confirmed presence of glass disease on the beads, those that did not have resin residues were cleaned using ethanol on microswabs, and loose areas of beading were stabilized using hair silk, which was available in the Winterthur Textile Conservation Lab and predyed to the appropriate color.

Based on the results of the collagen shrinkage temperature testing, it was deemed safe to humidify the coat overall to reduce distortions and realign the strips along the bottom. The object was placed on blotters and sealed in a chamber with beakers of a 30:70 ethanol:water solution. This solution was chosen as it is considered less aggressive than water alone and also reduces the risk of mold growth. The relative humidity (RH) was raised over a six-hour period to 80%, and the coat was allowed to sit overnight. RH was monitored using commercial humidity indicator cards. The coat was blocked with ethafoam, tissue, and nylon net and allowed to return to ambient conditions over three days.

Following humidification, areas of loss in the bottom wool strip were stabilized using cotton underlays toned with Golden Fluid Acrylics, and large or vulnerable losses in the skin were stabilized from both the interior and exterior using thin Hollytex precoated with a 1:1 mixture of Lascaux 360HV:Lascaux 498HV and reactivated using ethanol applied with a brush. A variety of Lascaux mixtures with various backings and reactivation methods were tested on a sympathetic piece of brain-tanned leather. The selected mixture was chosen due to its initial tack and reactivated strength. The Hollytex was toned prior to adhesive application using Golden Fluid Acrylics, and after application as necessary using colored pencils (Fig. 17).

Following treatment, the coat was rehoused with custom supports made of blueboard, ethafoam, and polyester fill to prevent further creasing (Fig. 18). Due to the fragile condition of the skin, further need for humidification should be prevented. The supports were covered with silk habotai, which was chosen due to its smooth finish and availability, to prevent abrasion or catching when removed. The coat is now stored in a custom blueboard tray on an undyed cotton sheet to act as a sling for safe handling.

Conclusion

Although this coat was brought to the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation for treatment, which primarily included cleaning and stabilization, technical analysis was deemed essential to carry out the necessary steps and provide valuable cultural context. Analysis of the skin included PLM of the hairs, PMF using MALDI-TOF to confirm the presence of reindeer and wolverine skins, and collagen shrinkage temperature testing, which confirmed that the skins were degraded but still able to withstand humidification.

Analysis of the beading included pH testing and residue analysis using FTIR. Based on these results, certain beads were cleaned to remove surface grime and slow the alkaline deterioration, while residues potentially significant to the coat’s use were left intact.

PLM was also conducted to confirm that the textile components are wool, and XRF analysis suggested the presence of a chrome mordant. During examination, a stamp associated with the Ushkov Company was discovered. More research into the history of this company with Russian-language scholars and Dolgan cultural historians is recommended.

This level of scientific analysis is infrequently conducted and available in English-language conservation studies of indigenous garments, and no other examples related to Dolgan material culture are known. Despite this coat’s extensive fur losses, it is a valuable example of Dolgan clothing, with its colorful textile decorations and beadwork and the confirmed use of both reindeer and wolverine furs. This technical analysis not only guided the treatment of the coat but also confirmed and furthered our understanding of Dolgan material culture. The coat is now conserved and more safely available for continuing research.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology for allowing me to study and treat this wonderful coat. Special thanks to Lynn Grant, Dr. Marie-Claude Boileau, and Dr. William Wierzbowski. This treatment was supervised by Lara Kaplan, with additional consultation from Laura Mina. I am grateful for their supervision and for allowing me to establish minor coursework in organic objects conservation, of which this treatment was a part. Analysis was conducted by Catherine Matsen and Dr. Rosie Grayburn at the Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. Access to the instrumentation at the Mass Spectrometry Facility at UD was made possible by the Delaware COBRE program, with a grant fron the National Institute of General Medical Sciences - NIGMS (5 P30 GM110758-02) with the National Institutes of Health. Amy Tjiong and Vera Solovyeva of the American Museum of Natural History consulted on the coat’s context. It is important to note that attempts to contact a representative of the Dolgan peoples were made but unfortunately unsuccessful given the project’s time frame and language differences. I truly believe that when studying and conserving indigenous material culture, collaborating with community stakeholders is best practice. I regret it was not possible in this instance.

Author Bio

Annabelle Camp is a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow in Textile Conservation with a minor in Organic Objects Conservation in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation Class of 2022.

Bibliography

Carrlee, Ellen. “Wolverine Fur.” Ellen Carrlee Conservation, 2008.

Czaplicka, Marie Antoinette. My Siberian Year; by M.a. Czaplicka, with Thirty-Two Illustrations from Photographs. London: Mills & Boon, 1916.

deYoung Museum. “IPR00001 Glue, animal, Shirish atha, Sam Monowar Jahan.” Ed. Beth Price, Boris Pretzel, and Suzanne Quillen Lomax. Infrared and Raman Users Group Spectral Database. Infrared and Raman Users Group, 2007. www.irug.org

“Dolgan.” Minorityrights.org, 2019. https://minorityrights.org/minorities/dolgan/.

Ellencarrlee.wordpress.com/2008/12/28/wolverine-fur.

Fitzhugh, William W, Aron Crowell, and National Museum of Natural History (U.S.). Crossroads of Continents : Cultures of Siberia and Alaska. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988.

Forsyth, James. A History of the Peoples of Siberia : Russia’s North Asian Colony, 1581-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Hall, Henry U. “The Siberian Expedition.” The Museum Journal/University of Pennsylvania. (1917): 27-45.

Klokkernes, Torunn. “Skin Processing Technology in Eurasian Reindeer Cultures : A Comparative Study in Material Science of Sàmi and Evenk Methods : Perspectives on Deterioration and Preservation of Museum Artefacts.” Dissertation, Langelands Museum, Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, 2007.

No Author. “100.A43 OLD SHELLAC” The Gettens Collection of Aged Materials of the Artist: FTIR Spectral Library and Catalog.

“100 Years of Research.” Expedition Magazine 26.1: Penn Museum, 1983. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/?p=4941.

Oakes, Jill E, Roderick R Riewe, and Bata Shoe Museum Foundation. Spirit of Siberia : Traditional Native Life, Clothing, and Footwear. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Moscow Times. “Russia shuts down Arctic indigenous rights group.” The Barents Observer, November 9, 2019. https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/arctic/2019/11/russia-shuts-down-arctic-indigenous-rights-group.

“Women’s hat, late 19th - early 20th century.” The Kuntskamera, 2018. http://collection.kunstkamera.ru/entity/OBJECT/326836?query=dolgan&index=58.

Ziker, John P. Peoples of the Tundra : Northern Siberians in the Post-Communist Transition. Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press, 2002.

Methods

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

PLM was completed using a 7.2 Color Mosaic microscope from Diagnostics Instruments. Images were taken using Spot RT Software v3.5.

Peptide Mass Fingerprinting (PMF) using Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) Mass Spectrometry (conducted at COBRA-funded facility.)

Rubbings were removed from the skins using an abrasive disc and solubilized in 30 µL trifluoroethanol, 30 µL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (AMBI) at 60ºC for 45 min with intermittent vortexing/agitation. They were digested with 8 µL trypsin (0.02 ug/µL in 50 mM AMBI) at 37ºC overnight.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis was then conducted. Alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (αCHCA) matrix was prepared as a saturated solution in 40% (v-v) acetonitrile (ACN) - 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Samples (4 µL) were mixed with matrix (20 µL) in a separate tube and spotted on the MALDI plate. Peptide standards were used as external calibrants, and a Bruker MicroFlex MALDI-TOF at the University of Delaware Mass Spectrometry facility was used to collect positive ion spectra from 800 to 3800Da with mass accuracy of ± 0.1 Da.

Collagen Shrinkage Temperature Testing

These tests were conducted using the hot table method. The system consists of a Mettler Toledo HS84 DSC hot stage coupled with a programmable HS-1 temperature controller and a Leica DM1000 microscope with an attached Olympus SC50 camera equipped with Olympus Stream software. Samples were prepared by pulling fibers from the skin using stainless-steel tweezers. The samples were soaked in deionized water and teased apart. The tests were recorded with temperature and time-stamp overlays. The tests started at room temperature and were raised 2°C per minute until the testing was believed to be complete.

X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Analysis was performed with a handheld Bruker Tracer III-SD XRF spectrometer using a rhodium tube (40kV high voltage, 9.6μA anode current, 25 μm Ti/305 μm Al filter) for 60 sec live-time irradiation. The spot size is oblong in shape, approximately 1 cm × 0.5 cm. Spectra were interpreted using the PXRF1 software.

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Sample material from the body of the coat was acquired with a stainless-steel scalpel and the aid of a stereomicroscope and then placed directly on a diamond cell. The material was rolled flat on the cell with a steel micro-roller to decrease thickness and increase transparency.

Sample material from the beads was removed using ethanol on a cotton swab. To extract the residue from the swab material, the material was redissolved in ethanol on a well slide. The ethanol was then evaporated, and the material was scraped off with a steel scalpel and placed on a diamond cell.

The samples were analyzed using the Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 FT-IR with Nicolet Continuum FT-IR microscope (transmission mode); data was acquired for 128 scans from 4000 to 650 cm^-1^ at a spectral resolution of 4 cm^-1^. Multiple scrapings of the sample were taken from the bulk sample, and multiple spectra were taken from different areas within each scraping. Spectra were collected with Omnic 8.0 software and analyzed in this program with various IRUG and commercial reference spectral libraries.

Materials

Blueboard: Corrugated board made from bleached, lignin-free, alpha-cellulose pulp. It is required to have a pH of 8.5-10.2, and contain alkaline sizing and an alkaline reserve (e.g., 3% calcium carbonate).

Cosmetic Sponges: Soft sponges made of non-latex polyurethane foam, marketed as a make-up applicator

Ethafoam: Closed-cell, low-density polyethylene foam made by injecting halogenated gas (dichlorodifluoromethane) into the polymer melt. Some products may contain stearyl stearamide (1%) as a slip agent, as well as trace amounts of antioxidants and UV absorbers. Manufactured by Dow Chemical Co.

Golden Fluid Acrylic Paints: Lightfast, low-viscosity acrylic paints with a high pigment load. Manufactured by Golden Artist Colors at art stores and from Golden Artist Colors.

Gore-Tex: Microporous, waterproof fabric composed of a membrane of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) laminated to a layer of nonwoven polyester; impermeable to liquids but transmits moisture and other vapors, and so may be used for humidification treatments. Manufactured by W. R. Gore & Associates.

Hair Silk: Fine silk thread.

Hollytex: Fabric made of white spun-bonded nonwoven polyester fibers calendared to a smooth surface. Available in a variety of thicknesses. Commonly used as a support material, interleaving paper, or backing.

Lascaux 360HV: Thermoplastic acrylic resin composed of water-based dispersion of butyl acrylate and methylmethacrylate thickened with acrylic butylester. Dry film is slightly tacky and can be used as a weak pressure-sensitive adhesive or reactivated with toluene, alcohol, or heat (50–55°C). The emulsion can be thinned with water, but the dry film is insoluble in water; Tg=-28°C; pH 8–9. Manufactured by Alois K. Diethelm, Switzerland.

Lascaux 498HV: Thermoplastic acrylic resin composed of water-based emulsion containing butyl acrylate thickened with methacrylic acid (40% solids). It can be thinned with water; the dry film is insoluble in water but soluble in acetone, ethanol, glycol esters, toluene, and xylene; Tg=6 ºC ; pH 8–9. Manufactured by Alois K. Diethelm, Switzerland.

Silk Habotai: Plain weave, silk fabric.

Vellux: Flocked, nylon textile.

Notes

Tiajono translates to “people of the tundra” and is how the peoples refer to themselves. John P. Ziker, Peoples of the Tundra: Northern Siberians in the Post-Communist Transition (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland, 2002), 4. ↩︎

Fulling is a finishing technique used on woven wool that creates a matted/felted surface on top of the weave that thickens the textile and makes it waterproof. ↩︎

Henry U. Hall, “The Siberian Expedition,” University of Pennsylvania Museum Journal 7 (1916): 28. ↩︎

“100 Years of Research,” Expedition Magazine 26, no. 1 (1983), https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/100-years-of-research/. ↩︎

William Fitzhugh et al., Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988), 71. ↩︎

Henry U. Hall, “The Siberian Expedition,” 35; Ziker, Peoples of the Tundra, 69. ↩︎

James Forsyth, A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia’s North Asian Colony, 1581–1990 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 177. ↩︎

Ibid.; Jill Oakes et al., Spirit of Siberia: Traditional Native Life, Clothing and Footwear (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press in association with the Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, 1998), 104. ↩︎

Ziker, Peoples of the Tundra, 2. ↩︎

Marie Antoinette Czaplicka, My Siberian Year (London: Mills & Boon, 1916), 56. ↩︎

The term rovduga refers to suede deer and moose skins. <Clarify this note. “Rovduga” is not used elsewhere.> ↩︎

Torunn Klokkernes, “Skin Processing Technology in Eurasian Reindeer Cultures: A Comparative Study in Material Science of Sàmi and Evenk Methods; Perspectives on Deterioration and Preservation of Museum Artefacts” (PhD diss., Langelands Museum, Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, 2007), 11. ↩︎

Ibid., 63. ↩︎

Ibid., 64. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Object entry for “Women’s hat, late 19th–early 20th century,” Kuntskamera (Moscow), accessed November 29, 2021, http://collection.kunstkamera.ru/entity/OBJECT/326836?query=dolgan&index=58. ↩︎

Ellen Carrlee, “Wolverine Fur,” Ellen Carrlee Conservation, December 28, 2008,

https://ellencarrlee.wordpress.com/2008/12/28/wolverine-fur/. ↩︎

Klokkernes, “Skin Processing Technology,” 64. ↩︎

All analysis parameters are provided in “Methods” at the end of the article and listed in the order in which they are discussed. ↩︎

This method was chosen over other protein analyses as the necessary expertise and instrumentation was accessible through the University of Delaware and the SRAL at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. This was facilitated in part due to funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to build this capability at Winterthur. ↩︎

Klokkernes, “Skin Processing Technology,” 192. ↩︎

Ibid., 75, 192. ↩︎

Ziker, Peoples of the Tundra, 70. ↩︎

Ibid., 71. ↩︎

“Dolgan”; “Russia shuts down Arctic indigenous rights group,” Barents Observer, November 9, 2019. https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/arctic/2019/11/russia-shuts-down-arctic-indigenous-rights-group. ↩︎

The thread count for these remaining hood elements and tassels cannot be determined due to the presence of beading and the intact fulling. ↩︎

Email message to the author, January 19, 2021. ↩︎

Oakes et al., Spirit of Siberia, 102, 106, 107; “Dolgan.” The following Kunstkamera objects have beading similar to that on the coat: women’s winter boots (МАЭ № 4128-199/2), shaman’s boots (МАЭ № 5658-48/б), shaman’s breastplate (МАЭ № 5658-47). ↩︎

All treatment materials are detailed in “Materials” at the end of the article. ↩︎