Manet Across Media : Looking at Lola de Valence

Kathryn Kremnitzer

Introduction

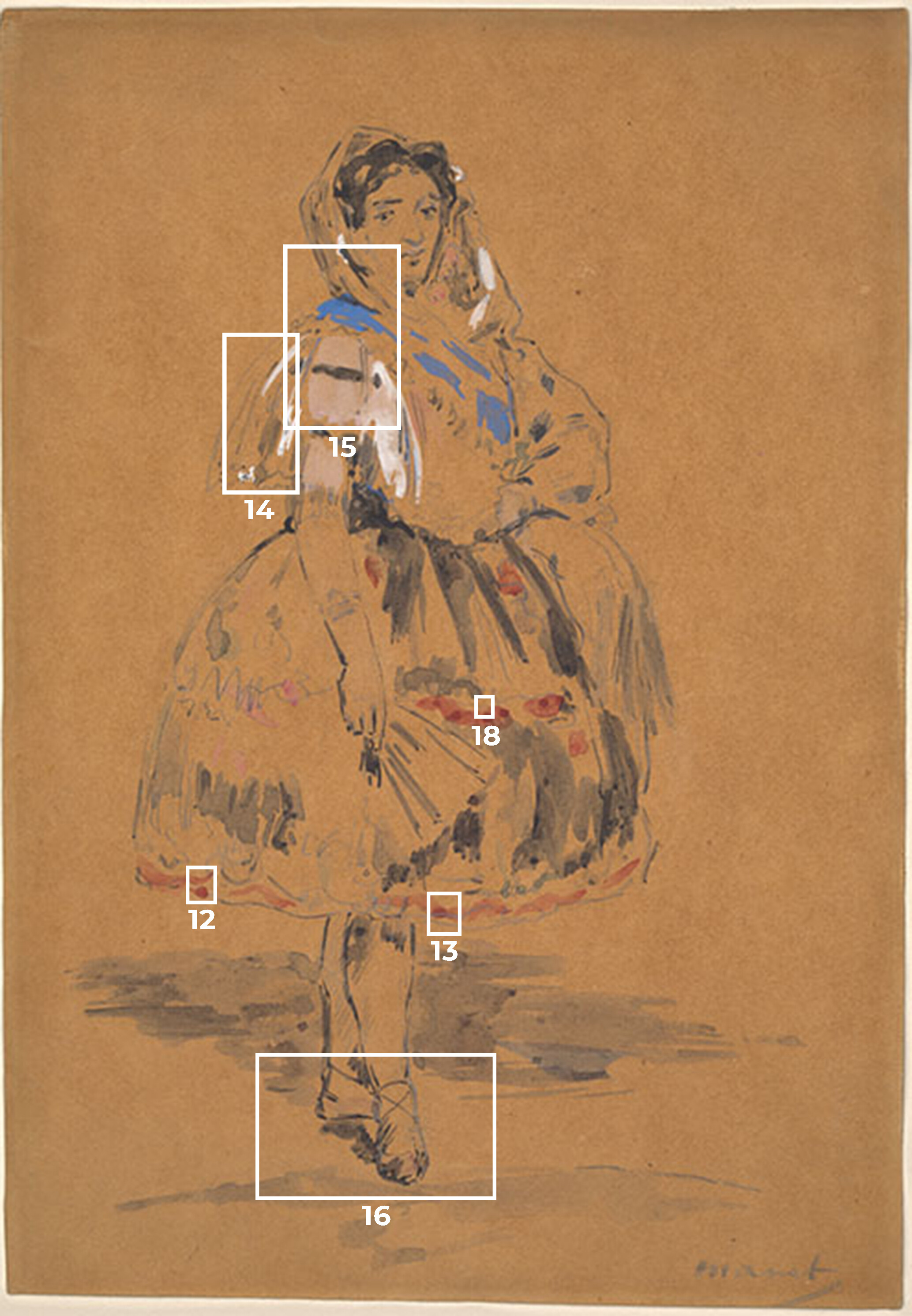

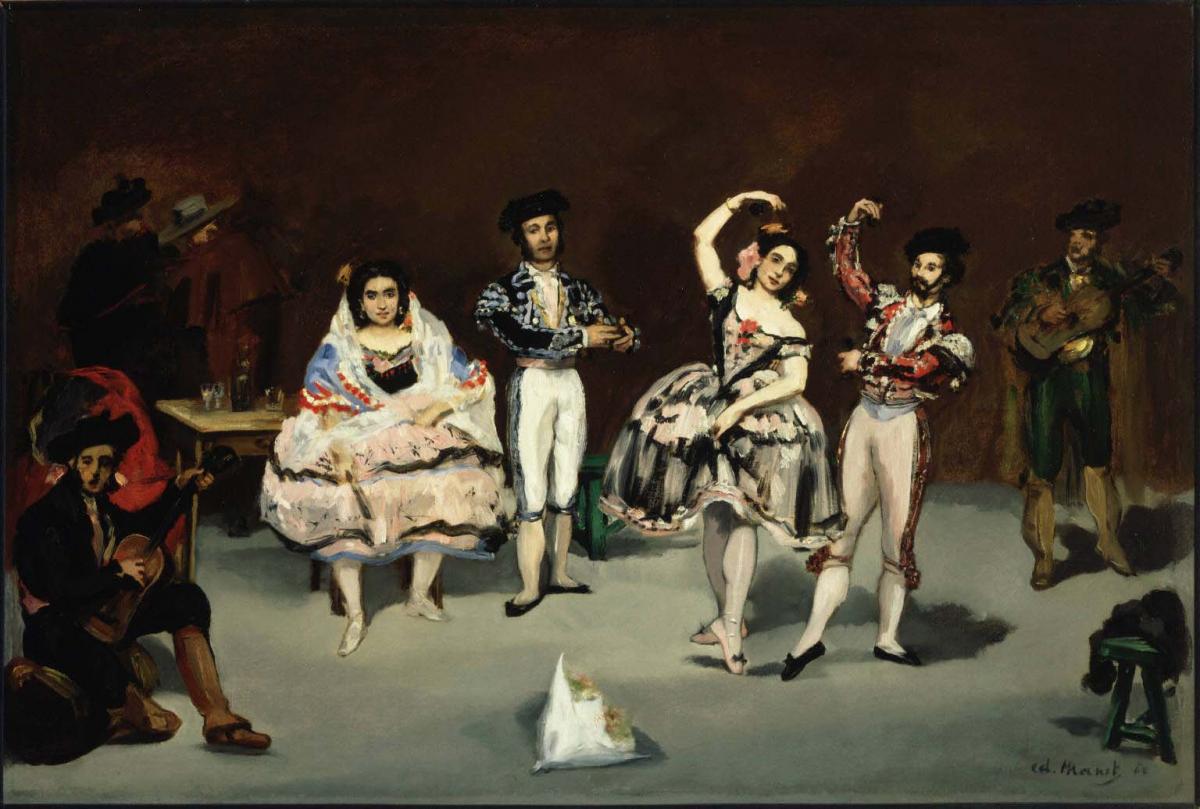

The following case study breaks from historically medium-specific divisions within museum collections and catalogue raisonnés to consider how Édouard Manet worked across media in the 1860s, and how a cross-media object-based approach to his work helps us to better understand each object individually and in context (Fig. 1).

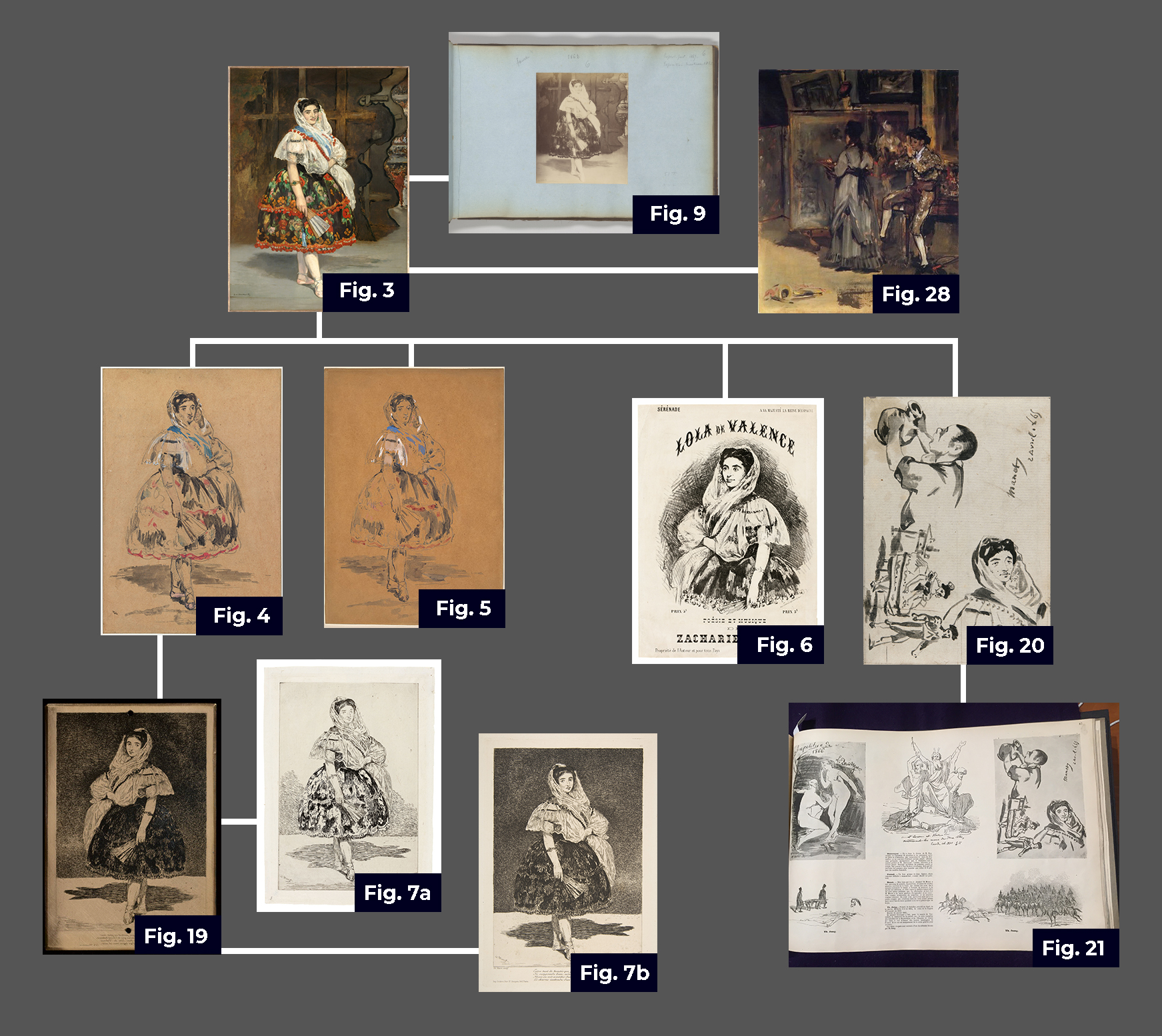

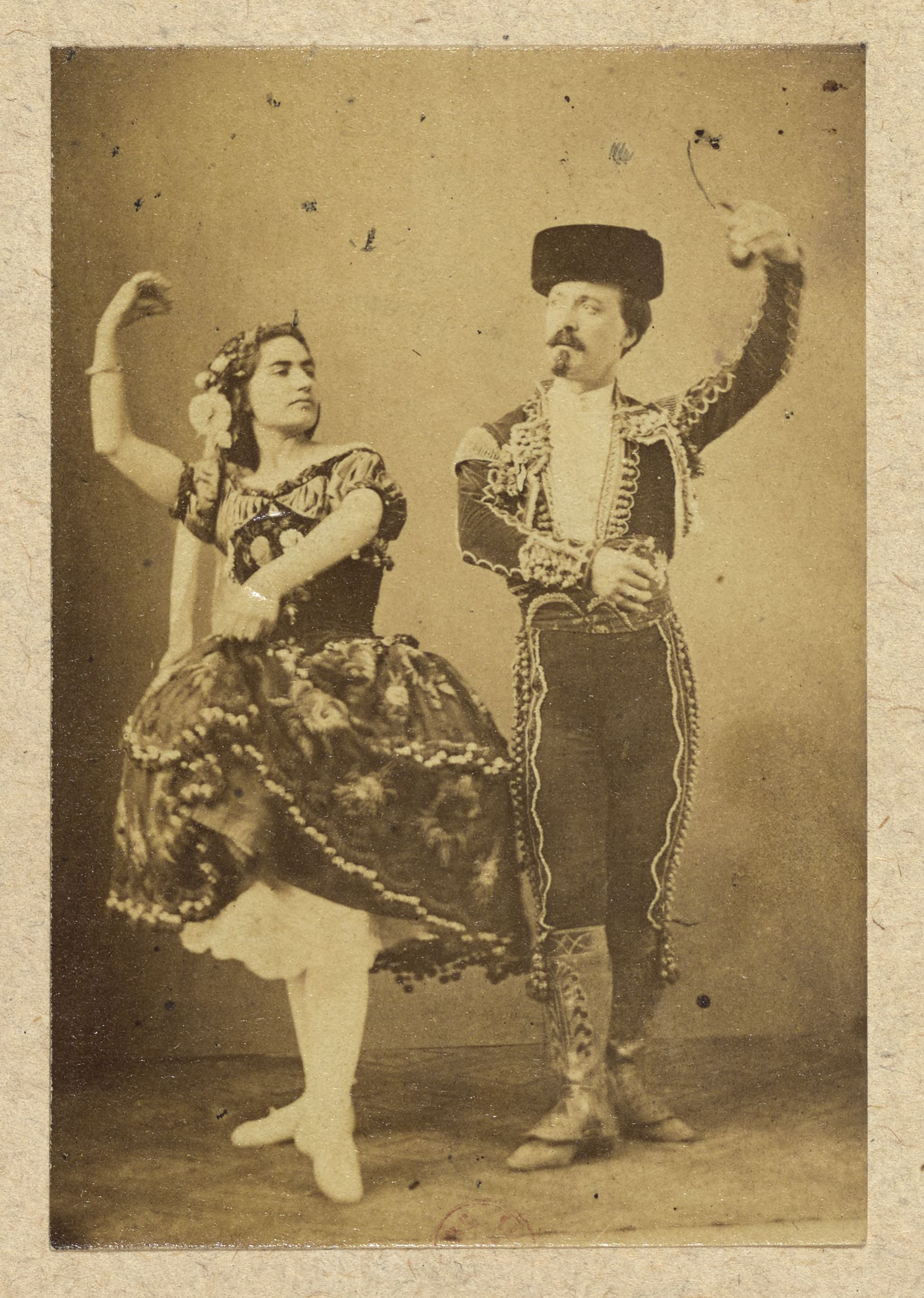

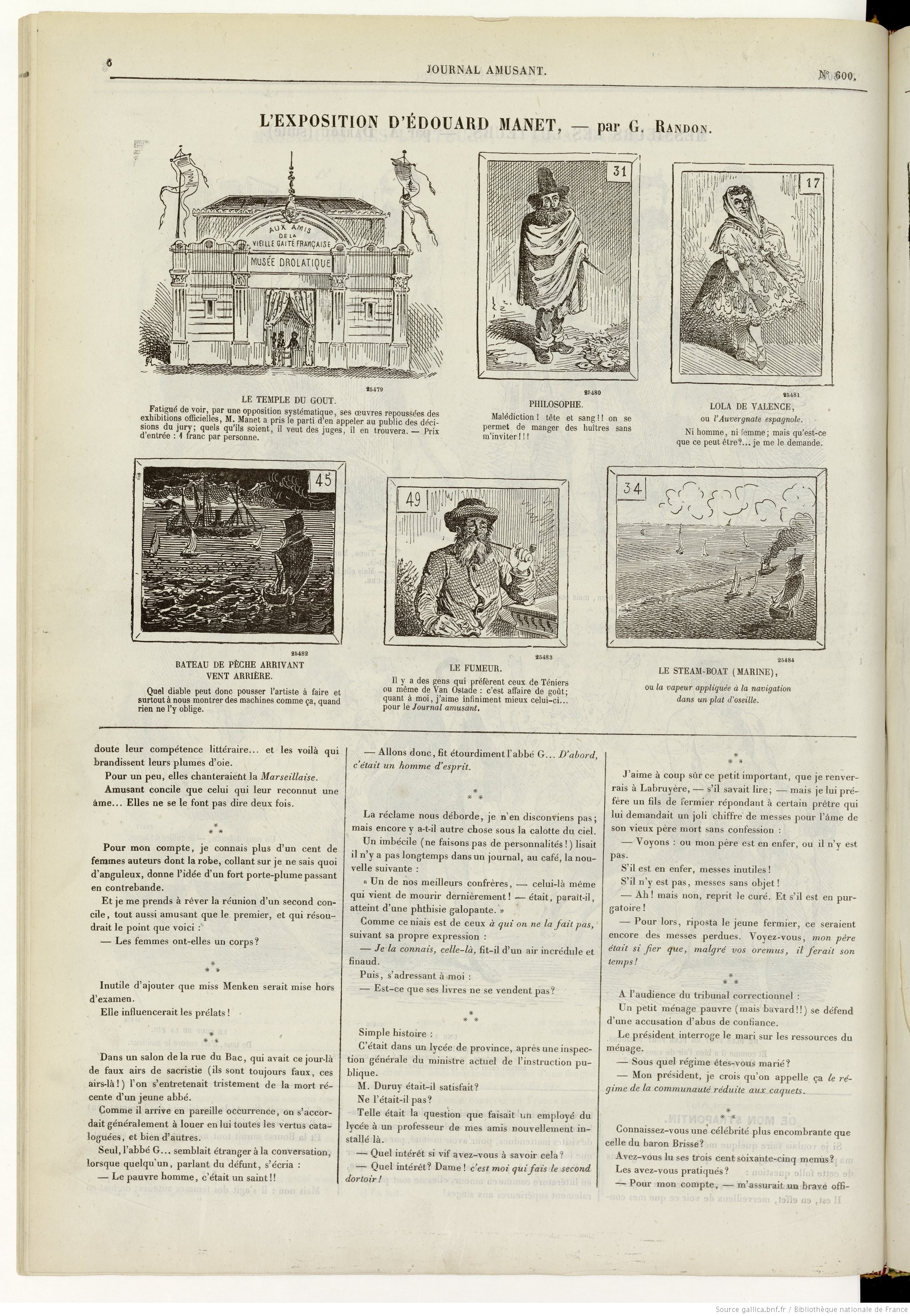

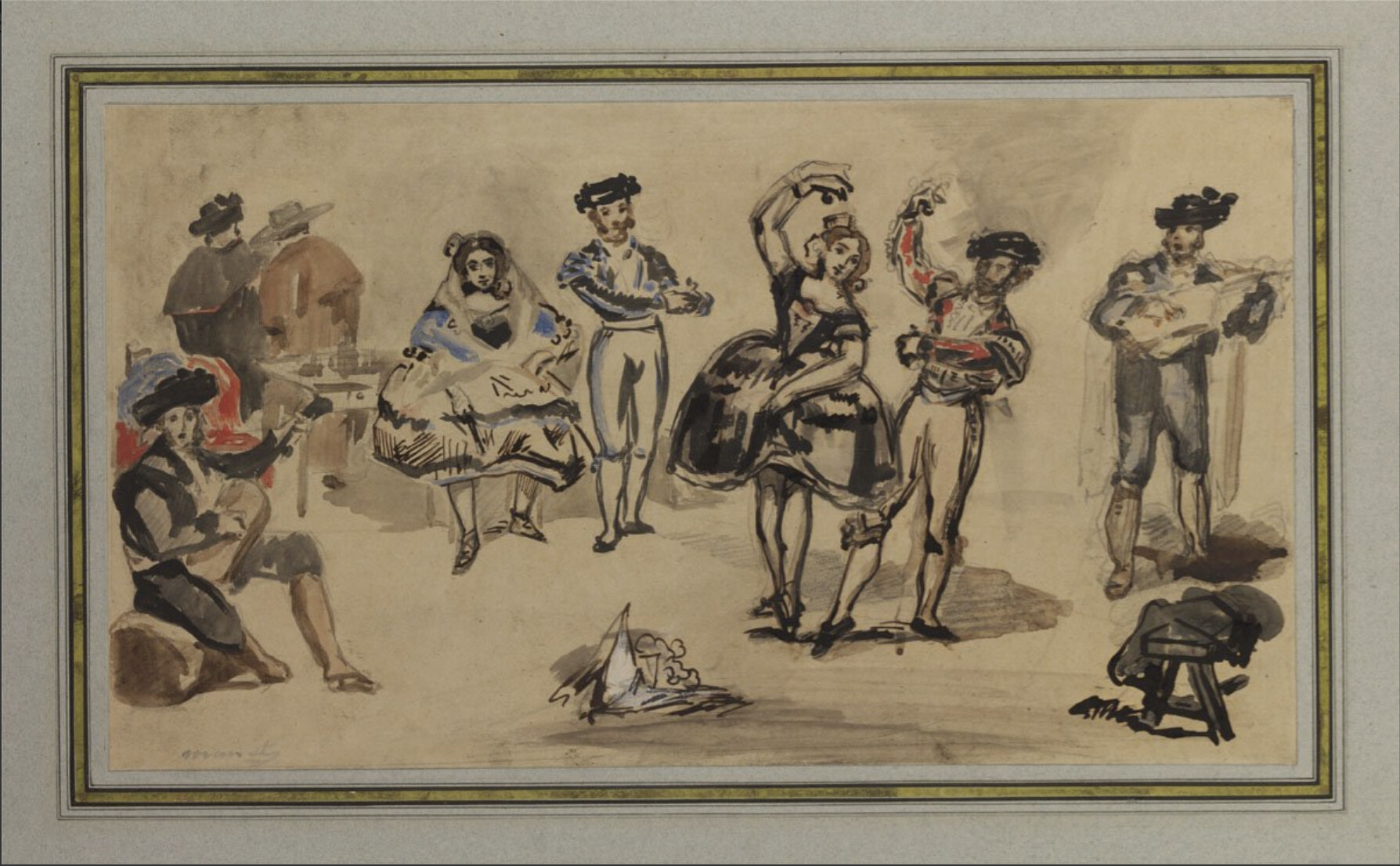

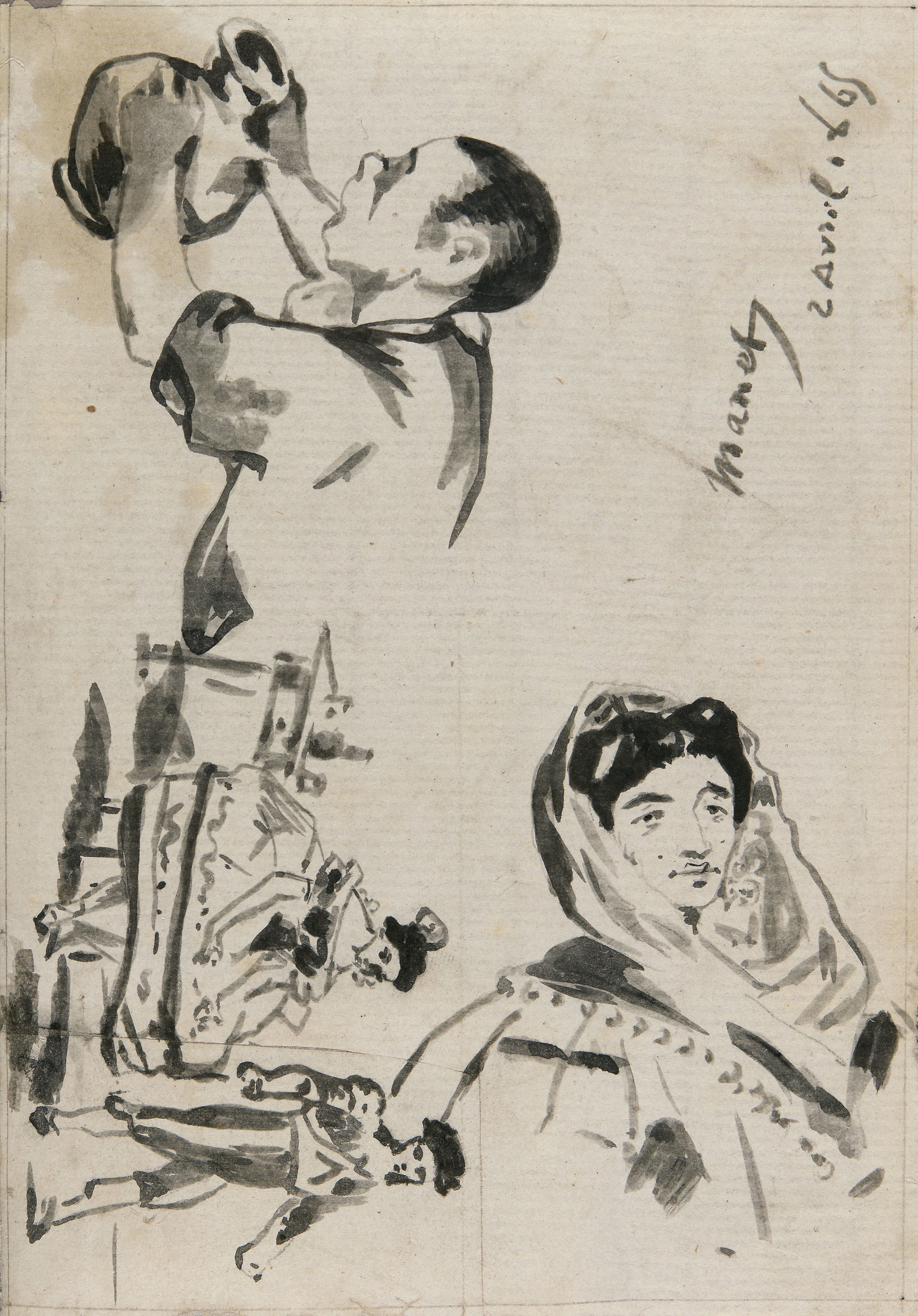

Lola Melea (Fig. 2) was the star ballerina of a troupe of Spanish dancers from the Royal Theater in Madrid that performed at the Hippodrome in Paris from August 12 through November 2, 1862. Manet first painted Lola in oil on canvas in 1862, then translated the composition twice, in watercolor, graphite, and ink and chalk, ink, and watercolor, before realizing the image as a lithograph for the cover of Zacharie Astruc’s serenade Lola de Valence and an etching in 1863 (Figs. 3–7a, 7b). Within a year of beginning the canvas, the painting, lithograph, and etching were all available to Parisian audiences—on exhibition and for sale—suggesting that the reality of a composition existing in different and numerous formats was not only known but appreciated.1 What follows aims to clarify the relationship between these works and the watercolors in particular.

The Painting

Manet probably painted Melea from life in his studio, posing her at rest, her feet in fourth position.2 At first Manet placed Melea on a plain background, captured in a caricature of the painting by G. Randon published on June 29, 1867, in Le journal amusant as part of a suite illustrating Manet’s solo show at the Avenue de l’Alma that May (Fig. 8), and in the watercolors and etching Manet made after the painting. In both watercolors, one at the Musée d’Orsay (Fig. 4) and the other at the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum (Fig. 5), Manet adapts the painted composition to the radically reduced scale of the paper sheet, anticipating the copperplate while maintaining the orientation of the painting. Thought at one time to be preparatory to the painting, the watercolors were in fact made from the painting before the etching.3 The addition of aquatint for the final state of the etching may have inspired Manet to revisit the painting, which he reworked, enlarging the canvas at top and bottom and adding the present background, sometime during or after June 1867, recognizing perhaps in the smaller monochromatic scale of printmaking something that could inform his painting. 4 Manet had the painting in his possession and could therefore literally draw from it until 1873, when he sold it to the opera singer Jean-Baptiste Faure, a friend and one of his most important collectors.5 How exactly Manet transcribed the composition from canvas to paper for the watercolor is not known, although it is likely that he used a photograph of the painting (Fig. 9) to trace the composition at a reduced scale.6 The Louvre watercolor, previously in the collection of Comte Isaac de Camondo, who by July 1893 owned the painting as well, bears incision marks, suggesting it was used to transfer the image to the copperplate to make the etching.7 The Harvard watercolor (Fig. 5), given by the artist to Zacharie Astruc as a gift, is considered to be an “autograph replica” of the Orsay watercolor (Fig. 4). That Manet would make a watercolor to prepare a monochrome etching is curious though consistent with his working method in the 1860s of translating painted compositions through watercolor to print; that there are two watercolors of Lola de Valence is even more puzzling. Why make a watercolor at all? And why twice? The technical findings that follow were an attempt to better understand the order of operations on each sheet and to contextualize their function within Manet’s larger pictorial project. The new visual evidence and observations outlined below, generated collaboratively through object-based study in conversation with curators, conservators, and conservation scientists, begin to shed light on these fundamental questions about Manet’s work as a draftsman and across media.

The Watercolors

In the Orsay watercolor (Fig. 4), Manet first faintly sketched the composition in graphite, then refined lines in pen and black ink before adding touches of color wash, white highlights in gouache, and reinforcements in a darker graphite, using either a different pencil or greater pressure than the first round. The brown paper sheet, signed “Manet” at bottom right in a grayish-blue wash and stamped by the Louvre when it officially entered the collection in 1911, may have been trimmed and is mounted on a secondary paper support that obfuscates the verso, stymying analysis in transmitted light.8 The watercolor’s surface has been incised in part—most visible in raking light (Fig. 10)—at times departing from the drawn contours but consistent with those in the etching, indicating that a tracing was made and reversed for transfer to the copperplate to prepare the etching.9 Jay Fisher surmised that Manet must have incised the verso of the sheet to ensure proper orientation of the etching when it was printed.10 Formal technical analysis of the Louvre watercolor, including pigment analysis, reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), and infrared imaging (IR), was not possible but could clarify particulars about the paper support and applied media as well as Manet’s technique. Thanks to conservators at the Fogg Museum, we were able to carry out more extensive technical analysis on the Harvard watercolor as part of this research.11 What follows are the results of these numerous examination sessions and ongoing conversations.

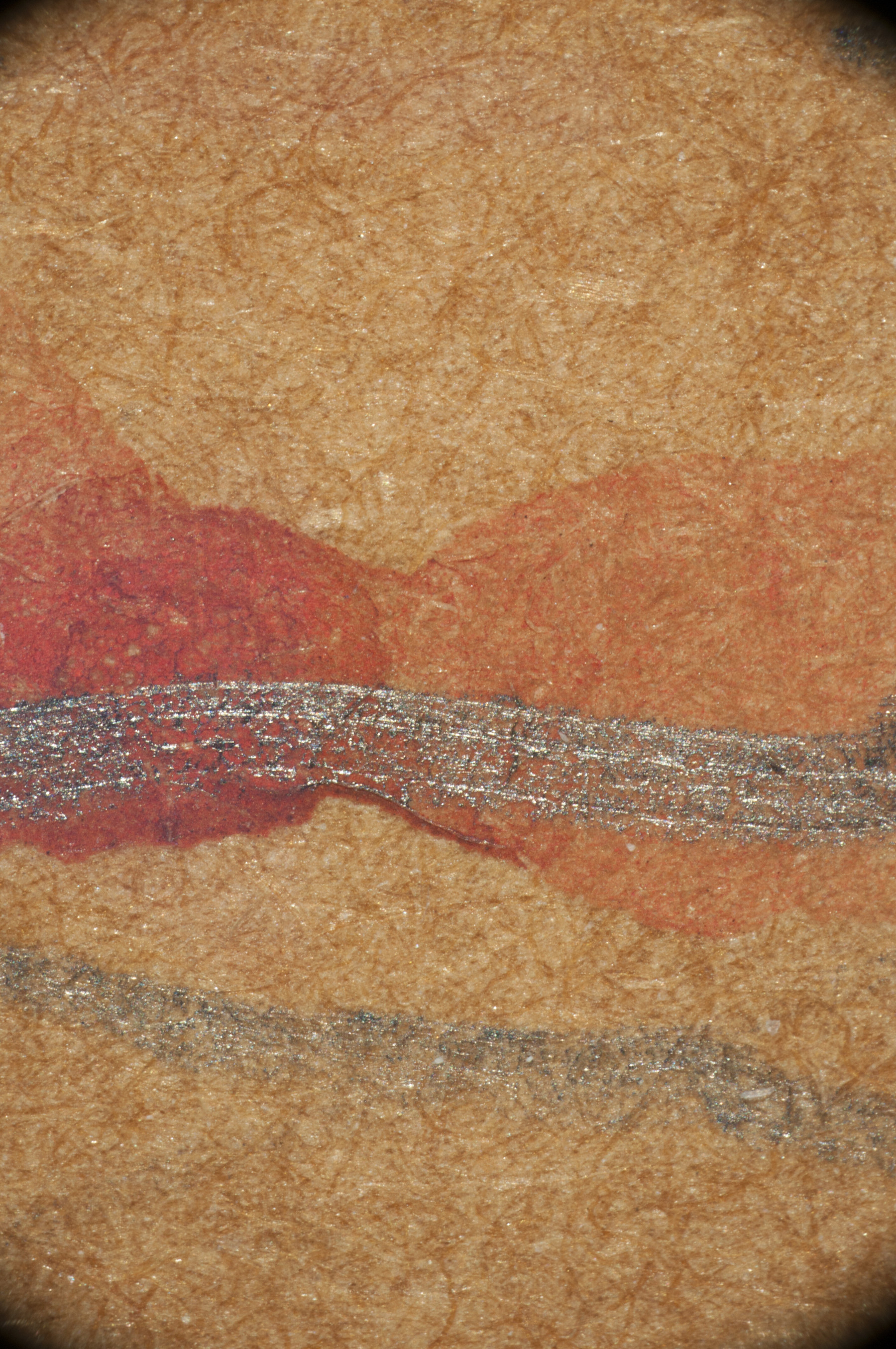

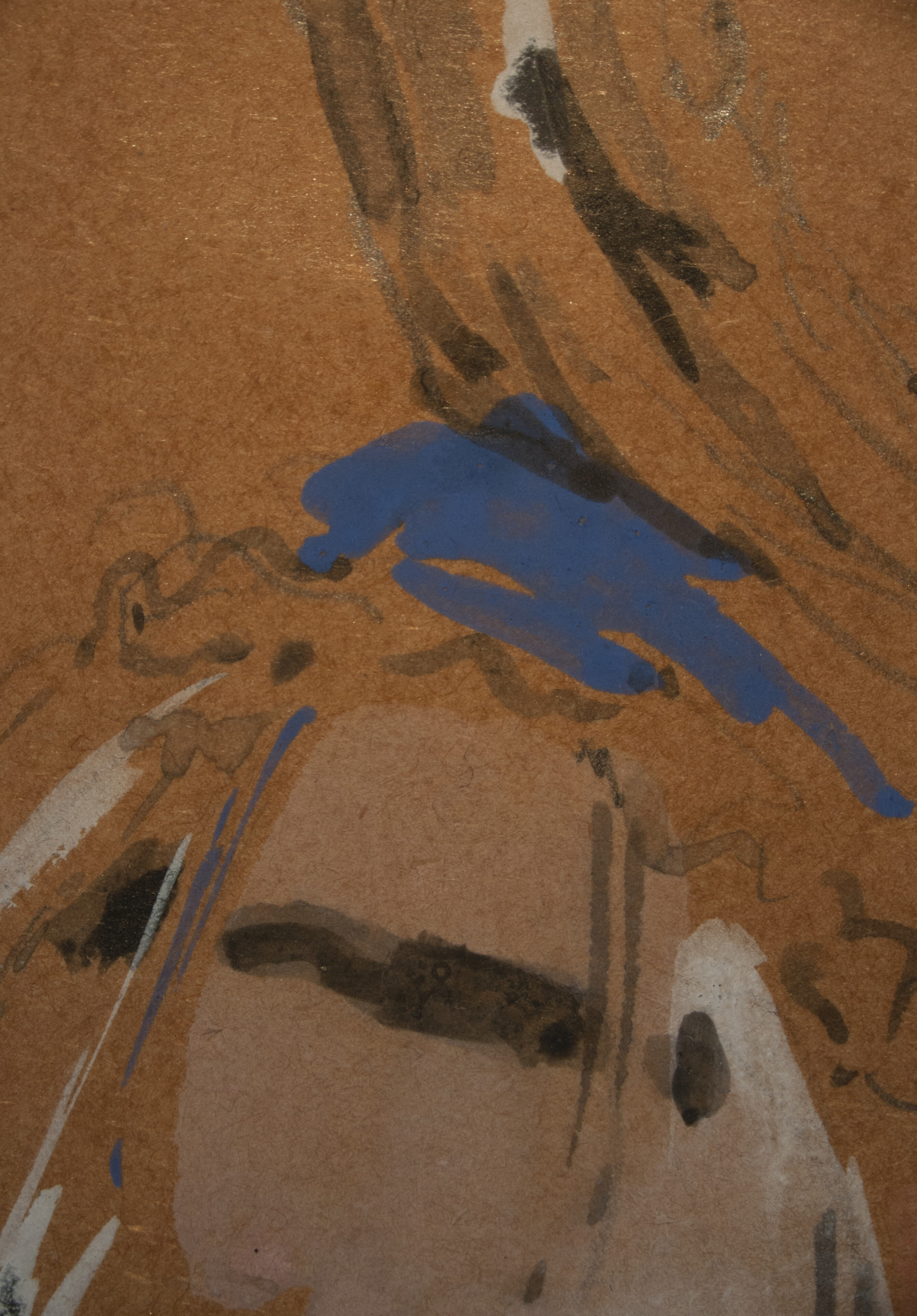

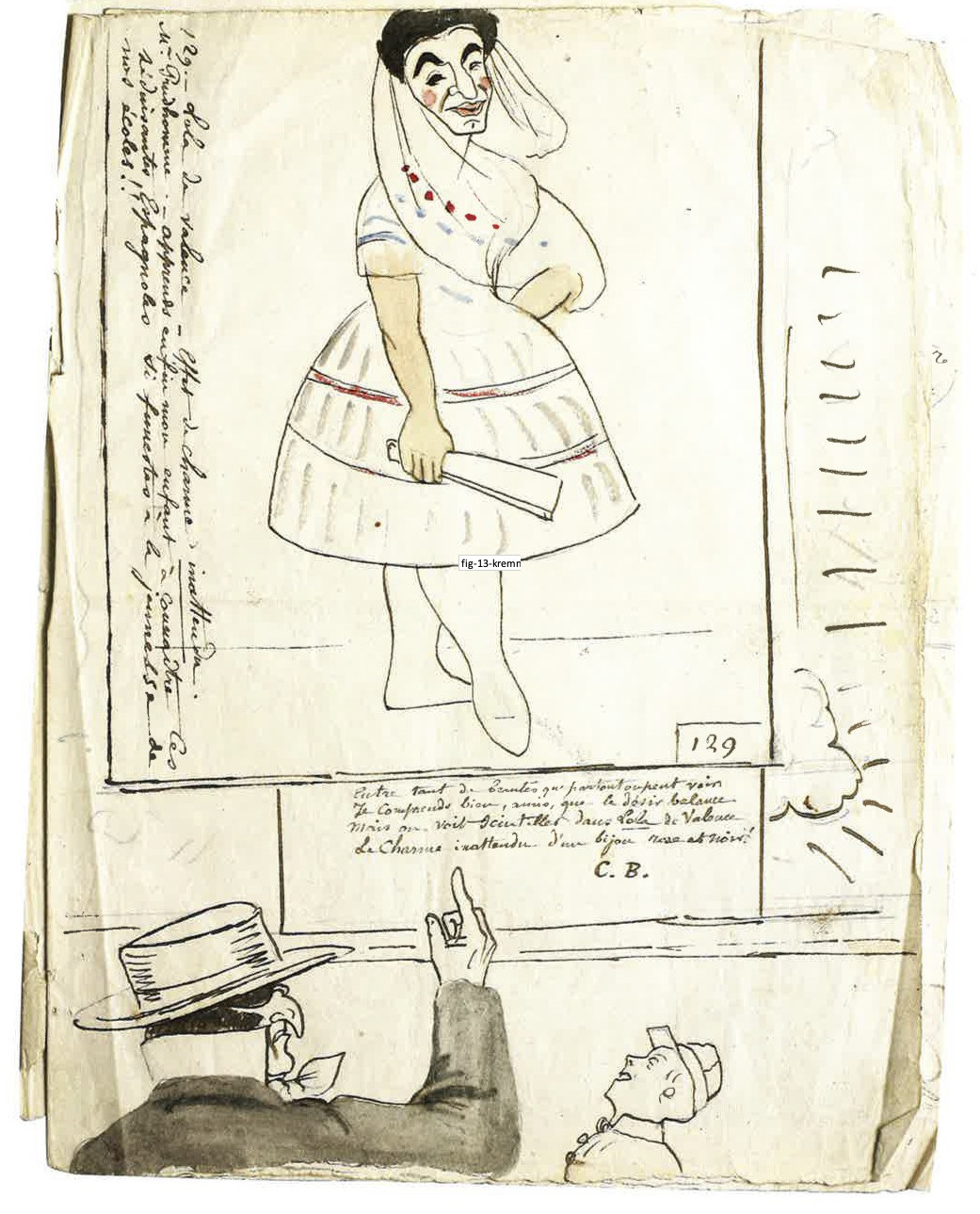

In the Harvard watercolor (Fig. 5), Manet first sketched the composition in graphite, refining lines in pen and ink before adding touches of wash and highlights in gouache, after which several elements were reinstated in graphite. This second campaign in graphite, in both watercolors, suggests color was a foundational part of the composition, rather than an afterthought or a later addition. Under magnification (Fig. 11) graphite is visible beneath and on top of watercolor additions (Fig. 12); for example, in Lola’s skirt, graphite sits both beneath and on top of touches of red. The watercolor’s opacity varies at times, indicating areas that are more and less diluted (Fig. 13). Unlike the Louvre watercolor, some of the gouache highlights in the Harvard watercolor have oxidized in particularly opaque passages, a phenomenon more visible under magnification (Fig. 14), indicating that the pigment used was lead-white, also confirmed by Raman spectroscopy.12 The red pigment has been identified as vermilion, and work is ongoing to determine the blue pigment, which is the most opaque of the three colors (Fig. 15).13 Manet also used a pink wash in Lola’s face, costume, and ballet shoes (Fig. 16), a color that has now largely faded. In the slippers, we again see evidence of graphite both beneath and on top of applications of black wash, indicating that Manet used graphite to sketch the initial composition, as well as to reinstate significant lines.

While the surface of the watercolor is not incised, making the purpose for which it was specifically designed unclear, the verso reveals persuasive clues about its making. Indications of the greater pressure and/or sharpened pencil used for the second campaign in graphite, notably in the bottom of the skirt, are perceptible in raking light and visualized more comprehensively using RTI (Fig. 17).14 The smooth, medium-thick wove paper has darkened to an orangish-brown color; the recto is uniformly shiny, the result of an as-yet unidentified, evenly applied coating, indicating that the paper was probably commercially treated.15 Matte patches on the right and left edges perhaps indicate where the sheet was held when the coating may have been applied. This fibrous paper is unusual in color and has more texture than Manet’s other early watercolors. The long fibers are not fully distributed, as is more clearly visible under magnification, revealing that the sheet was not fully beaten in the papermaking process (Fig. 18), and suggesting that the paper was probably made for more utilitarian purposes. The surface is abraded throughout, at the bottom of the skirt, for example—probably due to erasure, which pulled up fibers to reveal a lighter brown color probably closer to the original paper color.

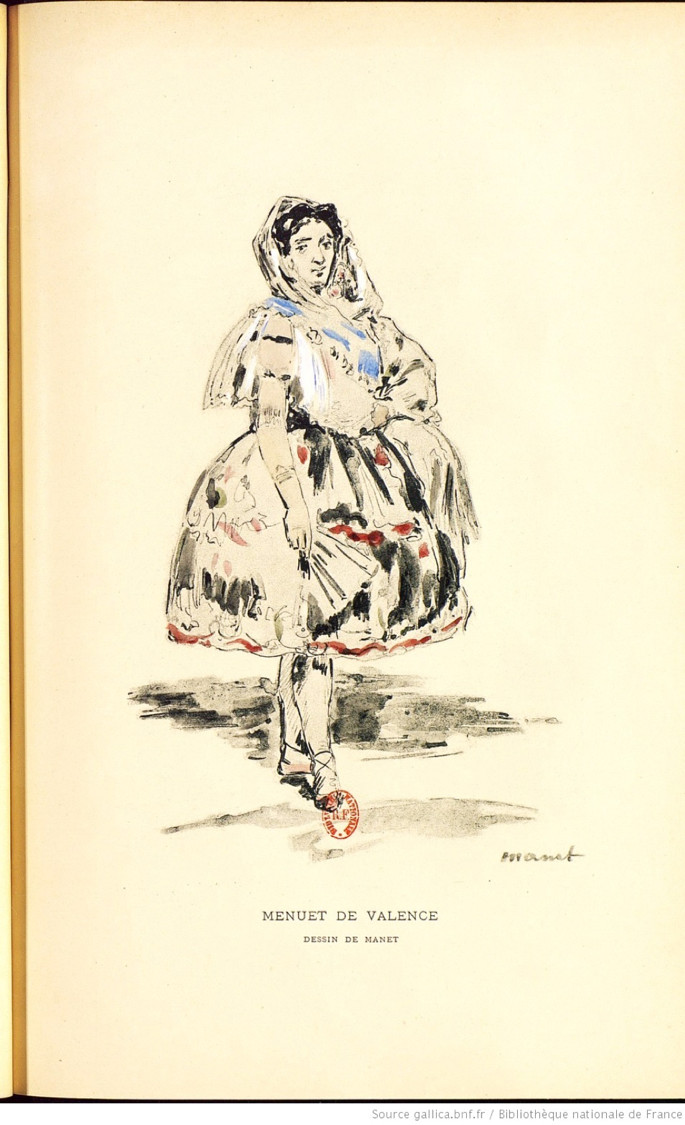

Manet gave the watercolor to Zacharie Astruc on the occasion of the composer’s serenade, also titled Lola de Valence, for which the artist had designed a lithographic cover (Fig. 6).16 Manet adapted the composition to the size of the cover such that her fan, and even his signature, curve to fit a circular configuration. Unlike successive states of the intaglio print, in which Manet returned to and reworked the copperplate, he drew directly onto the lithographic stone, producing a single state. The lithograph, published by Lemercier et Compagnie, registered by the Dépôt Legal on March 7, 1863, and on sale for 3 francs, predates etched versions of the painting.17

The watercolor (Fig. 5) does not appear to have been offered at Astruc’s collection sale in April 1878, but Ernest Chesneau, who wrote an introduction to the available watercolors and sculptures, praised Astruc’s appreciation for watercolor, a medium “considered generally by our painters as an easy and quick notation method” but admired by Astruc for “the conscientiousness and seriousness of an art that can say everything, translate everything, express everything, which, further, thanks to the simplicity of its chemical elements, escapes risks of alteration and destruction that menaces all painting in oil.”18 Astruc seems to have kept the drawing until his death in 1907, and it is reproduced in color in a posthumous collection of his poems, Alhambras, published in 1908, with the caption “Menuet de Valence / dessin de Manet” (Valence minuet / drawing by Manet) (Fig. 19).19 The watercolor (Fig. 5) later entered the collection of a Mlle Dieterle, a hitherto unidentified woman of the art-dealing family specializing in Corot, after which it was in the possession of Jacques Seligmann & Co. from at least 1934–36 before it was sold on December 1, 1936, to the New York dealer Martin Birnbaum for Grenville L. Winthrop, who upon his death in 1943 bequeathed his collection to the Fogg Art Museum.20

Correspondence between Birnbaum, Winthrop, and others reveals that the dealer considered the watercolor to be a “study of the famous portrait of ‘Lola,’ full length, in the Louvre,” failing to grasp that it was made from, not for, the painting, a confusion that runs through documentation of its eventual acquisition by the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum.21 Birnbaum first wrote to Winthrop of the drawing from Paris on November 24, 1936:

In spite of conditions, I am tempted to buy an important and very cheap water colour drawing for you. It is a Manet, a complete study of the famous portrait of “Lola,” full length, in the Louvre. She was a Spanish dancer, and probably posed often for Manet’s Spanish pictures. The price asked is 25000 francs, but I know my vendor well, and I am [sure]{.ul} it will cost [you]{.ul} considerably less, [even with my commission]{.ul}. However, I must ask you to cable authority to buy, as I hope to leave cold and wet Paris as soon as my errands have been attended to. . . .

I should add that the water colour drawing was owned by Manet’s friend Zacharie Astruc, and is reproduced in [coloured facsimile]{.ul} in the book “Les Alhambras,” p. 552, but less than the original size, which is 15 x 25 centimeters.22

Six days later, Winthrop sent Birnbaum a concise and decisive cable reading “Buy Manet,” to which Birnbaum replied by cable on December 1: “Drawing bought twenty three thousand one hundred francs.”23 Birnbaum also shared the news with Paul Sachs, then associate director of the Fogg, whom he wrote on December 1:

I have just acquired for Mr. G. L. W. an important [water colour drawing]{.ul} by Manet, a complete study of the “Lola de Valence” in the Louvre (Camondo Coll’n). It was given to Astruc, the poet-sculptor by his friend Manet, and is reproduced in colour in his book of poems, now very rare. — You will, I feel certain, approve this addition to the already important group of Manet drawings.24

Sachs responded somewhat prosaically on December 30, “I shall look forward with impatience to seeing the water-colour drawing by Manet, a complete study for the Lola which you have acquired for Mr. Winthrop,” again confusing the watercolor’s place in the order of production with respect to the painting and failing to realize its connection to the etching.25

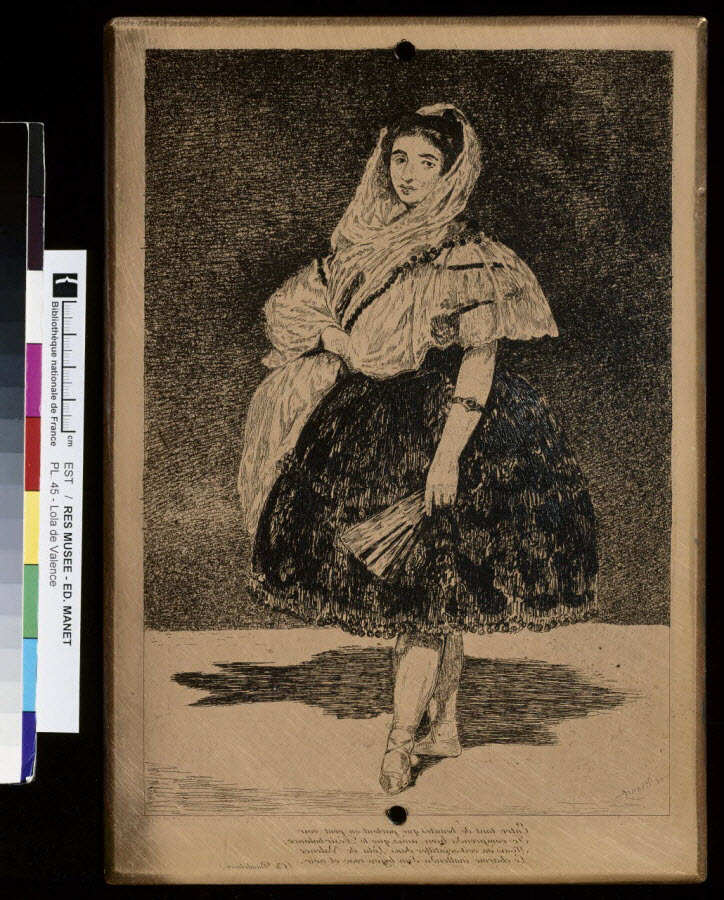

The Etching

The etching, in the same orientation as the painting and drawings, was built up in layers across several states and published in two editions in Manet’s lifetime.26 The first state, in pure etching, exists in one known proof on ivory laid Japanese paper, previously in the collection of Philippe Burty and Edgar Degas and now at the Art Institute of Chicago (Fig. 7a). The catalogue for Degas’s collection sale in 1918 lists various impressions of Lola de Valence, each with a brief description, the rarest of which, the first state impression, is illustrated:

226. Lola de Valence / Très belle et fort rare épreuve du 1er état, à l’eau-forte pure.

227. La même estampe. / Très belle et très rare épreuve de 2e état, avant le fond d’aquatinte, sur chine volant.

228. La même estampe. / Très belle épreuve du 5e état, avant les addresses.

229. La même estampe. / Très belle épreuve du même état, tirée en bistre.27

That Degas owned multiple states of the Lola de Valence etching attests to his appreciation of distinctions between states and the uniqueness of each impression. The etching is signed “éd. Manet” at bottom left, and the foreground and background are left largely bare in the first state, with the exception of Lola’s shadow and the suggestion of a back wall, delineating where the horizontal floor ends and the vertical wall begins. It is perhaps in this state of the print that we see Manet’s agility as an etcher most clearly: while maintaining the voluminous opacity of her tiered skirt, he preserves the translucency of her ruffled sleeve, privileging details of costume over facial features.

Manet re-etched the plate in the second state of the print, elaborating her skirt and the shadows cast on the floor and wall, and establishing a more concrete sense of space in the foreground.28 In the third state, having secured the setting, Manet turns his attention to the figure, giving her greater weight, refining her costume and accessories, notably the bracelet, which had only been alluded to in the first two states, and employing a light wash of aquatint to bring out various shadows as well as the background.29 The composition was completed with a stronger aquatint in the fourth state. By the sixth and final state (Fig. 7b), the subject was reduced (at bottom), and several text elements were engraved for Cadart’s Société des Aquafortistes’s publication of October 1, 1863, including the number “67” in the upper right-hand corner; the name and address of the publisher, “Paris, Publié par A. CADART & LUQUET, Editeurs, 79 Rue Richelieu,” at bottom right; a quatrain by Baudelaire at center; and the name and address of the printer, “Imp. Delâtre, Rue St. Jacques, 3o3, Paris,” below at left. Manet’s authorship is acknowledged twice in the bottom left-hand corner, with his handwritten signature, “ed. Manet,” etched into the copperplate, and a secondary signature, “Ed. Manet sculpt,” engraved outside the pictorial frame. After seeing the painting in the artist’s studio, Baudelaire sent these lines for the etching with specific instructions that refer to the painting itself: “To be engraved in small bastard characters — Mind the spelling, the punctuation, and the capital letters. . . . It might perhaps be well to write these verses under the portrait [painting], too, either in the pigment with a brush, or in black letter on the frame:”30

Entre tant de beautés que partout on peut voir

Je comprends bien, amis, que le désir balance;

Mais on voit scintiller dans Lola de Valence

Le charme inattendu d’un bijou rose et noir.

(Among all the beauties that are to be seen

I understand, friends, Desire chooses with pain;

But one may see sparkling in Lola de Valence

The unforeseen charm of black-rose opaline.)31

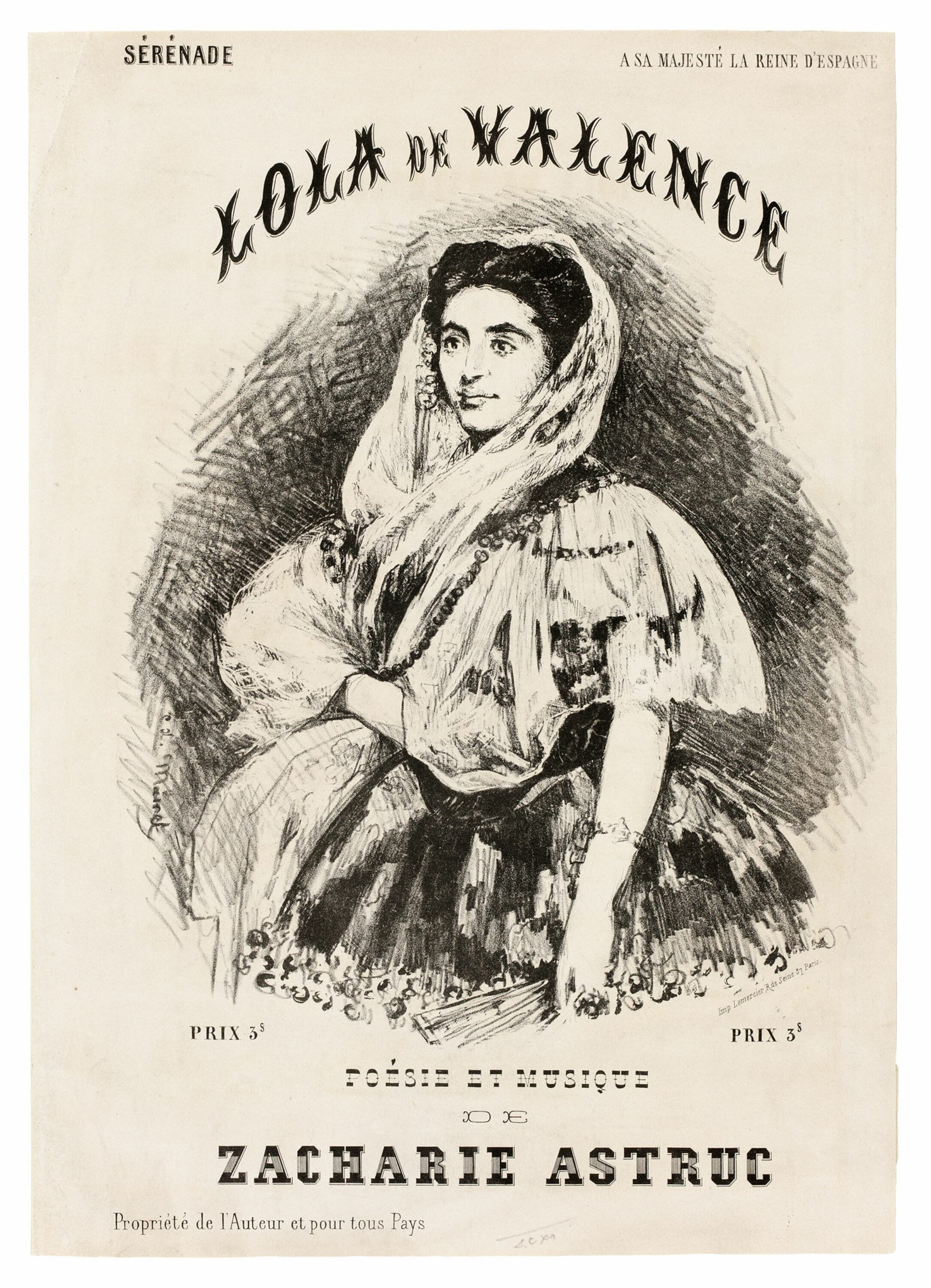

Manet seems to have adapted Baudelaire’s second suggestion, adding the verses on a cartouche attached to the painting’s frame for the 1863 and 1867 exhibitions, as illustrated in an unsigned caricature (Fig. 20). Baudelaire’s lines were engraved onto the copperplate, which was canceled with two holes at center top and bottom and is conserved at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Fig. 21).

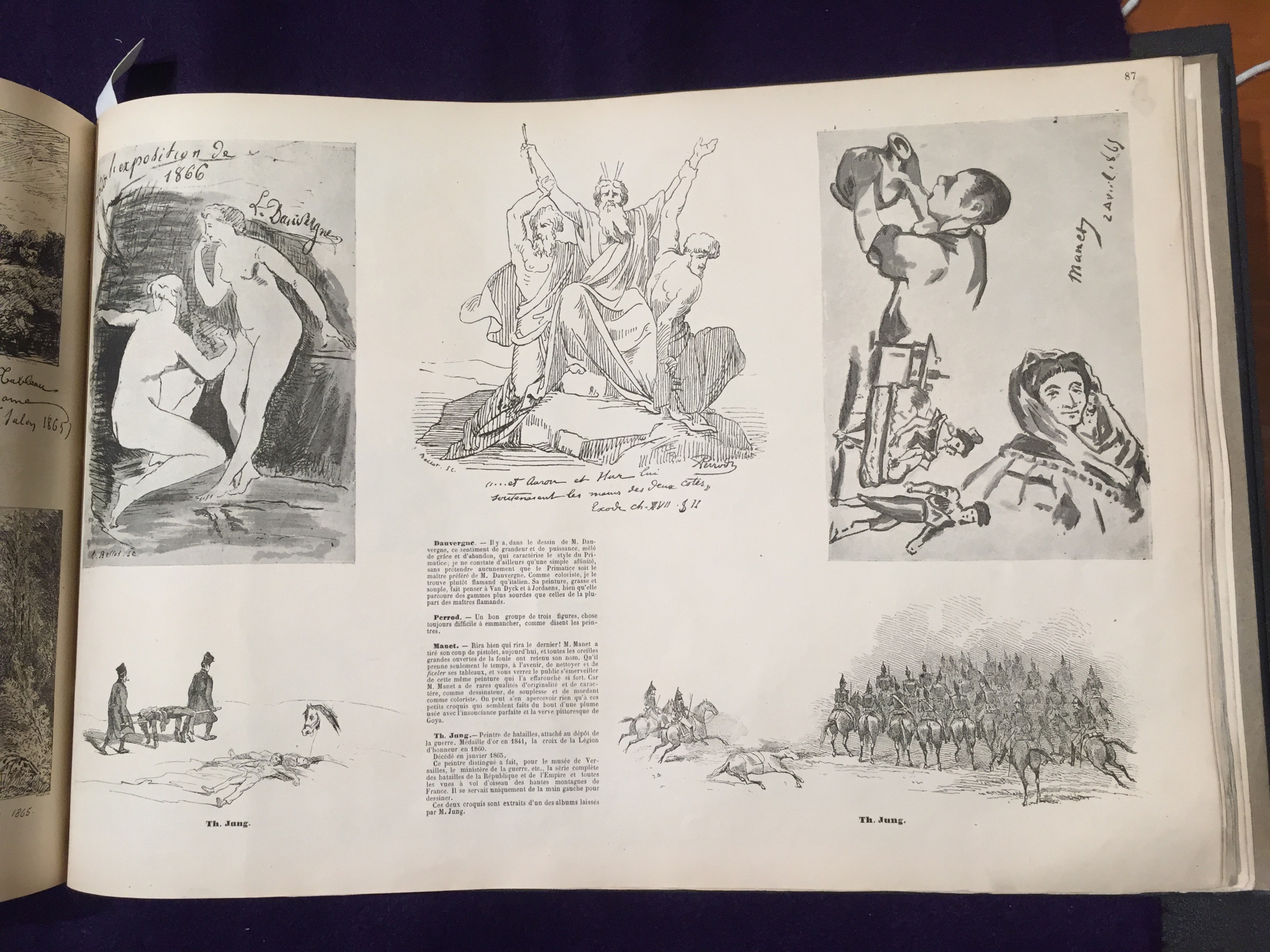

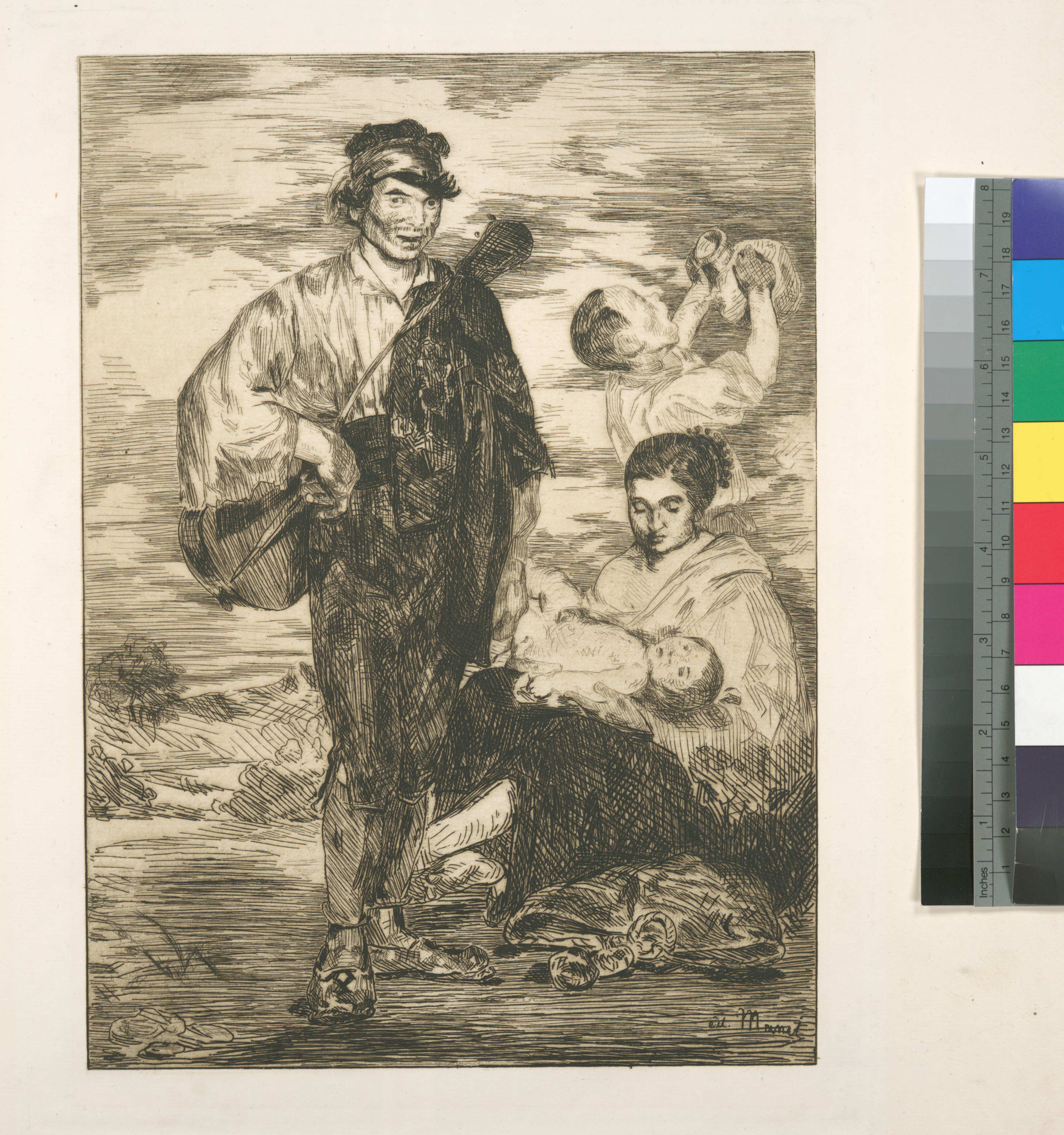

L’Autographe au Salon

Lola reappears in a sketch sheet by Manet signed and dated “Manet 2 Avril 1865” at the Art Institute of Chicago (Fig. 22).32 A handmade facsimile was prepared after the sheet to create an intermediary negative for the photomechanical reproduction process by which the drawing was published in the July 8 issue of Pigalle’s L’Autographe au Salon et dans les ateliers, an illustrated guide to the exhibition and its participants (Fig. 23).33 Manet had two paintings in the 1865 Salon that opened in May: Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers (The Art Institute of Chicago) and Olympia (Musée d’Orsay), both of which received relentless ridicule, and neither of which he chose to represent his participation in the exhibition. Rather, the drawing Manet selected to represent himself, and consequently his first published drawing, consists of three vignettes—all of which refer to paintings he showed at his breakout exhibition at the Galerie Martinet in early 1863: the bust of the drinking boy (Fig. 24) comes from The Gypsies (Les Gitanos), a scene Manet had painted and etched (Fig. 25) in 1862 and that by 1865 was a still-intact canvas, while the two small, full-length figures in Spanish dress relate to The Spanish Ballet—a painting (Fig. 26) of several members of the Spanish troupe that Manet also realized as a highly finished drawing (Fig. 27)—and the woman with the mantilla to his painting, Lola de Valence. 34

Recent technical analysis undertaken by the Art Institute of Chicago elucidates how Manet worked up this drawing, a synthesis of his latest Spanish-themed paintings, as well as its intermediary function.35 The drawing (Fig. 22) was first faintly laid in hard graphite, then, using a brush and slightly diluted ink, reinforced and selectively shaded, before an undiluted, thicker, and therefore blacker ink was applied for emphasis in, for example, the darker areas of Lola’s hair and shawl. The support, a light- to medium-weight, slightly textured ivory laid paper, now discolored to light gray, is similar to that found in many of Manet’s small sketchbooks, from which the sheet may have come.36 The sheet is in fact composed of two pieces of paper: Manet revised the pieced part of the drawing that replaced an initial sketch of the male dancer and carefully integrated the addition with the existing sketch, in the two lines on Lola’s shoulder, for example, and the rightmost part of the standing ballerina’s skirt, both of which extend over the new piece.37 Manet likely traced the couple, or at least the table and woman, from another graphite sketch, which, when scaled to match the size of the dancers in the Chicago sheet and overlaid, are a relative match. Unsurprisingly, the male dancers are not, as the Chicago figure was a revised version of the source drawing. The nuance of Manet’s sketches is largely lost in the printed version, which measures slightly smaller than the drawing and fails to reproduce the subtle tonal variations Manet achieved in ink and wash.38 The matrix of dots created by the half-tone screen in the published image is seen clearly under magnification (Fig. 28), but the process by which the image was photomechanically reproduced, likely by means of gillotage, requires further study. The published image is accompanied by an unsigned caption:

Rira bien qui rira le dernier! M. Manet a tiré son coup de pistolet, aujourd’hui, et toutes les oreilles grandes ouvertes de la foule ont retenu son nom. Qu’il prenne seulement le temps, à l’avenir, de nettoyer et de ficeler ses tableaux, et vous verrez le public s’émerveiller de cette même peinture qui l’a effarouché si fort. Car M. Manet a de rares qualités d’originalité et de caractère, comme dessinateur, de souplesse et de mordant comme coloriste. On peut s’en apercevoir rien qu’à ces petits croquis qui semblent faits du bout d’une plume usée avec l’insouciance parfaite et la verve pittoresque de Goya.39

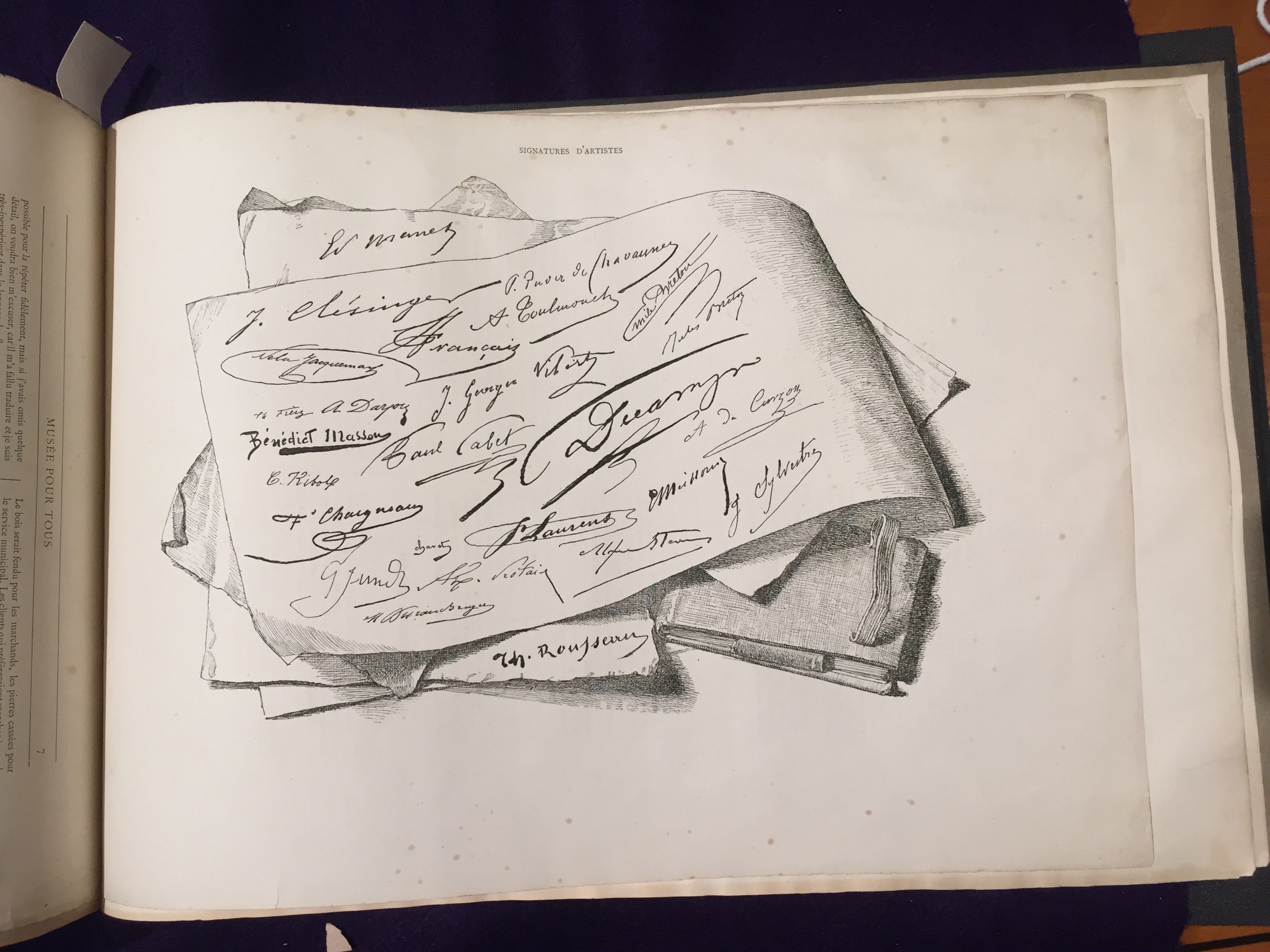

The anonymous commentator cleverly reminds the reader that what failed to satisfy traditional expectations of finish for conservative critics was championed by members of the avant-garde as “rares qualités,” perceptible even in “ces petits croquis” (these little sketches). Manet’s submission served as both a kind of signature, acknowledging his participation in the Salon exhibition, and a calling card, advertising, like Goya, his ability to translate “verve pittoresque” across media.40 Whereas Manet’s paintings at the Salon were seen as unrefined and derivative, this anonymous endorsement praises the exact qualities for which he had been ruthlessly ridiculed. Still, to consider this collection of “petits croquis” as the result of an “insouciance parfaite” undermines the attention with which Manet assembled the sheet. The three vignettes are not so much casual sketches as they are careful recollections, albeit reduced, that are drawn from earlier compositions and exemplify Manet’s sustained engagement across media with compositions he thought worthy, whether working out the images of old masters he admired or revisiting his own increasingly ambitious paintings. The appreciation for Manet as a draftsman extends to a page at the back of the publication, where, in response to readers’ requests, artists’ signatures are reproduced, including Manet’s, which appears on its own sheet beneath another with several signatures, together with a cloth-bound sketchbook (Fig. 29).41

Lola’s final appearance in Manet’s oeuvre is the sketchiest—as one of the finished paintings framed and against the wall between the two figures with others in his studio in an oil sketch of about 1869–70 (Fig. 30). The likeness is too summarily brushed to determine whether the background of the painting had already been reworked, but Lola’s appearance here as a painting, in this unfinished version, is perhaps its most tangible representation as an object, rather than an image.42

Conclusion

Manet translated his own painted compositions through watercolor and etching throughout the 1860s, an exercise he repeated for several of his most accomplished and controversial canvases, including Lola de Valence.43 Often poorly reproduced, little exhibited, and marginalized by scholarship bound to artistic hierarchies that privilege painting over works on paper, Manet’s early watercolors might be better understood as an essential link between his painting and printmaking. These watercolors enabled the artist to revisit and revise subjects beyond and apart from pressures of the official, state-sponsored Salon, on a scale more manageable than painting and in a medium less costly than canvas. There are many more questions yet to be answered but this study offers some insight into the creation and function of this important body of work, to consider the watercolors on their own material terms and to investigate new ways of looking thanks to technological advances. Studying the watercolors at close range yielded new insights about their individual making and Manet’s working methods across media, an approach that both inspired and motivated his artistic practice.

Acknowledgements

Thanks first and foremost to the entire Materia team and the two anonymous reviewers whose comments and collective efforts on my behalf were invaluable. Research undertaken for this article would not have been possible without the generosity of many scholars, curators, conservators, and conservation scientists who made their collections available and offered extraordinary collaboration. Sincere thanks to Leila Jarbouai, Curator of Drawings, and Géraldine Masson, Assistant Curator of Drawings at the Musée d’Orsay; Penley Knipe, Phillip and Lynn Straus Senior Conservator of Works of Art on Paper and Head of Paper Lab, Anne Driesse, Senior Conservator of Works of Art on Paper, Katherine Eremin, Patricia Cornwell Senior Conservation Scientist and Christina Taylor, Assistant Paper Conservator, at the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg, all of whom generously advanced my project beginning in Summer 2017 during The Summer Institute for Technical Studies in Art (SITSA) program; Kristi Dahm, Associate Conservator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago; Gonda Zsuzsa, Curator of 19th century Prints and Drawings at the Szépmüvészetti Múzeum in Budapest; Madeleine Viljoen, Curator of Prints and The Spencer Collection, Denise Stockman, Associate Paper Conservator, Senior Exhibition Conservators Myriam Dearteni and Grace Owen-Weiss, and the entire Prints and Photographs Study Room staff at The New York Public Library. And, as always, thanks to Juliet Wilson-Bareau for continued conversation on all things Manet.

Bio

Kathryn Kremnitzer earned her PhD in Art History at Columbia University in 2020 with a dissertation focused on Édouard Manet’s working across media in the 1860s. She was previously Research Associate in the Painting and Sculpture of Europe department at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she worked on Manet and Modern Beauty (2019), Monet and Chicago (2020), and Cezanne (2022), and contributed to the online scholarly catalogue of Manet’s works in the collection. As a Curatorial Assistant at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, she worked on Madame Cézanne (2014) and Tiepolo Caricatures from the Robert Lehman Collection (2014). She is currently Associate Vice President, Specialist in 19th Century European Paintings at Sotheby’s in New York.

Bibliography

Allan, Scott, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom. Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Last Years. Getty Publications, 2019.

Astruc, Zacharie. Les Alhambras. Paris, 1908.

Baudelaire, Charles. Oeuvres complètes. Edited by Claude Pichois. New ed. Vol. I. Paris: Gallimard, 1975.

Beeny, Emily A. “Manet, Cat. 8, Sketches from The Gypsies, The Spanish Ballet, and Lola de Valence for L’Autographe au Salon de 1865: Curatorial Entry,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago https://publications.artic.edu/manet/reader/manetart/section/140020 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017).

Cachin, Françoise, Charles S. Moffett, and Juliet Wilson-Bareau. Manet, 1832–1883. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983.

Catalogue des estampes anciennes et modernes…composant la collection Edgar Degas… Paris: Hôtel Druout, 1918.

Hanson, Anne Coffin. “Édouard Manet, ‘Les Gitanos’, and the Cut Canvas,” The Burlington Magazine 112, no. 804 (March 1970): XX-XX.

Harris, Jean C. Édouard Manet: The Graphic Works, A Catalogue Raisonné. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1990.

L’Estraz, Hector. “Promenade au Salon,” L’Intransigeant (May 2, 1881).

Locke, Nancy. Manet and the Family Romance. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Lussier, Stephanie M., Gregory D. Smith, Stephanie M. Lussier & Gregory D. Smith (2007) A review of the phenomenon of lead white darkening and its conversion treatment, Studies in Conservation, 52:sup1, 41-53, DOI: 10.1179/sic.2007.52.Supplement-1.41.

Owen, Antoinette. “Manet, Cat. 8, Sketches from The Gypsies, The Spanish Ballet, and Lola de Valence for L’Autographe au Salon de 1865: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago https://publications.artic.edu/manet/reader/manetart/section/140020 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017).

Petit, Galerie Georges. Catalogue des tableaux modernes, pastels, aquarelles, dessins … gravures, tableaux anciens … composant la collection de M. Max, Paris, 1917.

Tabarant, Adolphe. Manet et Ses Oeuvres. Paris: Gallimard, 1947.

Tinterow, Gary. Geneviève Lacambre, and Deborah L. Roldán. Manet/ Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.

Wilson-Bareau, Juliet. Édouard Manet: Das Graphische Werk: Meisterwerke aus Der Bibliothèque Nationale und Weiterer Sammlungen. Ingelheim am Rhein: C. H. Boehringer, 1977.

Wilson-Bareau, Juliet. Manet: dessins, aquarelles, eaux-fortes, lithographies, correspondance. Paris: Hugette Berès, 1978.

Wilson-Bareau, Juliet. “Manet’s One and Only Jeanne…and Guérard’s Later Plate,” Art in Print 8, 6 (April 2019).

Wolohojian, Stephan, ed. A Private Passion: 19th-Century Paintings and Drawings from the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection, Harvard University. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.

Notes

The painting was one of fourteen by Manet on view at Galerie Martinent in March 1863 (no. 129), and the etching was exhibited in the prints section of the Salon des Refusés in May 1863 (no. 676). ↩︎

Françoise Cachin, Charles Moffett, and Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet, 1832–1883 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art), 146, cat. 50. ↩︎

Adolphe Tabarant described them as preparatory to the painting: “deux études, dessin et aquarelle, ont précédé l’huile.” Tabarant, Manet et ses oeuvres (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), 53. ↩︎

Adolphe Tabarant, Manet: Histoire catalographique (Paris: Editions Montaigne, 1931), 81; Cachin, Moffett, and Wilson-Bareau, Manet, 1832–1883, 146, cat. 50. ↩︎

See “Provenance,” in Cachin, Moffett, and Wilson-Bareau, Manet, 1832–1883, 150, cat. 50. ↩︎

An overlay in Photoshop of the Harvard drawing with a photograph of the painting in volume 1 of the Godet album did not align; with proper measurements of the photograph, the same could be done with the photograph in volume 2. See Anatole Godet, Two albums of photographs of the work of Edouard Manet, vol. 1, p. 6, Morgan Library & Museum (MA3950), https://www.themorgan.org/literary-historical/338004; Godet, Reproductions de tableaux d’Édouard Manet: photographies, vol. 2, n.p., Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8432387g/f17.item. ↩︎

The watercolor, together with the painting, entered the Louvre in 1911 as part of the Bequest of Count Isaac de Camondo. The watercolor’s earlier provenance is not known. ↩︎

Cachin, Moffett, and Wilson-Bareau, Manet, 1832–1883, 150, cat. 50. ↩︎

Alain de Leiris, The Drawings of Édouard Manet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), 150. ↩︎

Jay McKean Fisher, The Prints of Édouard Manet (Washington, DC: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1985), 60, cat. 25. ↩︎

Thanks to Anne Driesse, Katherine Eremin, and Penley Knipe for their assistance during and beyond the 2017 Summer Institute for Technical Studies in Art at the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum. ↩︎

On the darkening of lead white pigments, see Stephanie M. Lussier and Gregory D. Smith, “A Review of the Phenomenon of Lead White Darkening and Its Conversion Treatment,” supp. 1, Studies in Conservation 52 (2007): 41–53, doi: 10.1179/sic.2007.52.Supplement-1.41. ↩︎

Thanks to Katherine Eremin for carrying out pigment analysis in 2017 that revealed the white is lead white (basic lead carbonate) and the red is vermilion (mercuric sulfide). ↩︎

Thanks to Christina Taylor for capturing and processing RTI images of the Harvard watercolor. ↩︎

Wove paper is a type of handmade or machine-made paper formed on a mold screen of finely woven wires, lacking the pattern of laid and chain lines that characterizes laid paper. The identification of the paper’s thickness, texture, and color is according to Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston, 1996). ↩︎

The music and words, written in rhyme, were dedicated to the queen of Spain and her empress, Eugenia, of Spanish origin, who had married Emperor Napoleon III ten years earlier in January 1853. On the lithograph, see Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet: Dessins, aquarelles, eaux-fortes, lithographies, correspondance (Paris: Hugette Berès, 1978), no. 73 (unpaginated). ↩︎

Jean C. Harris, Édouard Manet: The Graphic Work; A Catalogue Raisonné, rev. ed. (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1990), 117–18; Cachin, Moffett, and Wilson-Bareau, Manet, 1832–1883, 154. ↩︎

“Nos peintres, en général, considèrent l’aquarelle comme un simple moyen de notation facile et rapide; M. Astruc est de ceux qui la traitent, au contraire, avec la conscience et le sérieux d’un art qui peut tout dire, tout traduire, tout exprimer; qui de plus, grâce à la simplicité de ses éléments chimiques, échappe aux risques d’altération et de destruction dont toute peinture à l’huile est menacée.” Tableaux anciens et modernes, aquarelles et sculptures par Zacharie Astruc, sculpture diverses, meubles, objets d’art: Collection de Z. Astruc . . . vente . . . 11 et 12 Avril 1878 (Paris, 1878), 59. ↩︎

Zacharie Astruc, Les Alhambras (Paris, 1908), 553. ↩︎

The group of Manet drawings in Winthrop’s collection may have already by this time included two watercolors, Portrait of Gilbert-Marcellin Desboutin (c. 1875) and Race Course at Longchamp (1864) , and a drawing on the verso of an albumen photograph of Jeanne (Spring) (c. 1881-82). On Winthrop’s collection, see Stephan Wolohojian, ed., A Private Passion: 19th-Century Paintings and Drawings from the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection, Harvard University (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003). On Manet’s watercolor Race Course at Longchamp, see Juliet Wilson-Bareau with Kathryn Kremnitzer and Genevieve Westerby, The Races at Longchamp, in Manet: Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), cat. 12 (cited hereafter as Manet [AIC]). On Manet’s drawing of Jeanne (Spring), see Wilson-Bareau, “Manet’s One and Only Jeanne . . . and Guérard’s Later Plate*,” Art in Print* 8, no. 6 (April 2019): 36–41; Scott Allan, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom, *Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Last Years* (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2019), 48–49. ↩︎

An undated, handwritten, crossed-out label in the curatorial file at Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum confirms this confusion: “There is another watercolour of the same subject; more highly finished; in the Louvre, Collection Camondo. Both are studies for the oil painting, also in the Collection Camondo, painted in 1862.” A graphite inscription at bottom left reads “In Petit sale cat. May 11/ 1917,” but according to the sale catalogue, no work by Manet was offered. See Galerie Georges Petit, Catalogue des tableaux modernes, pastels, aquarelles, dessins . . . gravures, tableaux anciens . . . composant la collection de M. Max (Paris, 1917). ↩︎

Birnbaum to Winthrop, letter, November 24, 1936, Paris, curatorial object file, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum (cited hereafter as Harvard/Fogg). ↩︎

Winthrop to Birnbaum, cable, November 30, 1936; and Birnbaum to Winthrop, cable, December 1, 1936, curatorial object file, Harvard/Fogg. ↩︎

Birnbaum to Sachs, letter, December 1, 1936, curatorial object file, Harvard/Fogg. ↩︎

Sachs to Birnbaum, letter, December 30, 1936, curatorial object file, Harvard/Fogg. ↩︎

Juliet Wilson-Bareau details the etching across eight states and six editions in Wilson-Bareau, Manet: Dessins, aquarelles, eaux-fortes, lithographies, correspondence, as opposed to the “five or six” states enumerated in Wilson-Bareau, Édouard Manet: Das Graphische Werk; Meisterwerke aus Der Bibliothèque Nationale und Weiterer Sammlungen (Ingelheim am Rhein: C. H. Boehringer, 1977). Editions of the print appeared in 1863, 1874, 1890, 1894, 1905, and 1976. My discussion excludes posthumous states and editions. ↩︎

Catalogue des estampes anciennes et modernes . . . composant la collection Edgar Degas (Paris: Hôtel Druout, 1918), 43, nos. 226–29. ↩︎

Wilson-Bareau, Édouard Manet: Das Graphische Werk, no. 29. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

As translated in Cachin, Moffett, and Wilson-Bareau, Manet, 1832–1883, 148, cat. 50. ↩︎

Charles Baudelaire, Oeuvres complètes, ed. Claude Pichois, new ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1975), 1:168; as translated in Cachin, Moffett, and Wilson-Bareau, Manet, 1832–1883, 148, cat. 50. ↩︎

For a full art historical and technical discussion of Manet’s sketch sheet, see Emily A. Beeny, Sketches from “The Gypsies,” “The Spanish Ballet”, and “Lola de Valence” for “L’Autographe au Salon de 1865, in Manet (AIC), cat. 8. ↩︎

Antoinette Owen, “Technical Report,” Sketches from “The Gypsies,” “The Spanish Ballet,” and “Lola de Valence,” in Manet (AIC), cat. 8, paragraph 13. ↩︎

For discussion of Manet’s Les Gitanos, see Emily A. Beeny, Boy with Pitcher (La Régalade), in Manet (AIC), cat. 14; Anne Coffin Hanson, “Édouard Manet, ‘Les Gitanos’, and the Cut Canvas,” Burlington Magazine 112, no. 804 (March 1970): 158–67. ↩︎

Owen, “Technical Report,” paragraph 25. ↩︎

Antoinette Owen notes there are tiny pinholes in all four corners of the support at the intersection of the ruled graphite lines, likely made during the reproduction process. For a full technical discussion of the media and support, see ibid. ↩︎

The inserted sheet is clearly visible in transmitted IR, and a beta radiograph of the drawing shows the chain lines in the inserted paper do not align with those of the main sheet, although they are both laid paper. See ibid., figs. 8.21, 8.22. ↩︎

Manet’s sketch sheet measures 18.1 🞨 12.7 cm, while the printed version measures slightly smaller, 17.5 🞨 12 cm. See ibid., para 14. ↩︎

L’Autographe au Salon de 1865 et dans les ateliers, July 8, 1865, 87. “He who laughs last laughs best! M. Manet has fired his shot today, and the crowd, with ears wide open, has heard his name. If only he can learn to take the time to tidy up and finish off his pictures, you shall see the public marvel at the same painting that has lately caused it such alarm. For M. Manet has rare qualities: originality and character as a draftsman, fluidity and intensity as a colorist. You see it even in these little sketches, which look as though they were made using the tip of a worn quill, with the perfect nonchalance and the picturesque verve of Goya.” Translated in Beeny, “Sketches from “The Gypsies,” “The Spanish Ballet,” and “Lola de Valence,” paragraph 4. The phrase coup de pistolet, or “firing a shot,” was used to describe disruptive acts of artistic provocation in the Salon by which an artist might garner attention—firing into the crowd, as it were. Hector L’Estraz contextualized the phrase in the May 2, 1881, installment of his “Promenade au Salon,” which appeared serially in L’Intransigeant, and helped to clarify its figurative intent: “Aujourd’hui on passera sans les voir, ces oeuvres honnêtes, qui ne font pas de tapage; dans la presse de ce premier jour, avec le désir qu’on a de tout voir, ceux qui ne sont pas de haute taille, ou qui n’ont pas su tirer un coup de pistolet pour attrouper la foule, ne seront pas remarqués.” ↩︎

Manet borrowed this self-marketing strategy of advertising abilities across media from Goya himself, who cleverly called attention to his work as a printmaker, for example, in his painted portrait of Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.41): a bird on a string held by the young sitter holds a small etched calling card in its beak on which the artist’s name, “L Franco Goya” is written below a painter’s palette, brushes, and assorted accessories. The painting is not only a representation of the young Manuel but a commercially inflected reminder of Goya’s work as both a painter and printmaker. ↩︎

As L. Baschet, managing director of the publication wrote on the preceding page, “Pour répondre au désir de nos lecteurs, nous consacrons de nouveau notre quatrième page à la reproduction d’un certain nombre de signatures d’artistes. Tout ce qui éclaire le caractère d’un personnage connu, tout ce qui fournit quelques détails sur sa personnalité a pris en effet depuis quelques années une considérable importance” [To respond to the desires of our readers, we newly dedicated our fourth page to the reproduction of a certain number of artists’ signatures. All that illuminates the character of a known person, all that furnishes certain details about his personality indeed took in recent years a considerable importance.] ↩︎

For further discussion of Manet’s unfinished Eva Gonzales Painting in Manet’s Studio, now in a private collection, see Juliet Wilson-Bareau’s entry for Lola de Valence in Gary Tinterow, Geneviève Lacambre, and Deborah L. Roldán. Manet/Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), 490, esp. n2, cat. 138; Nancy Locke, Manet and the Family Romance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 128. ↩︎

For more on this practice, see Kathryn Kremnitzer, “Manet’s Watercolors: Transition and Translation in the 1860s (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2020). ↩︎