“Richness of Colour and Boldness of Outline” : On Annie Walke’s Artistic Practice

Maria Vittoria Pellini and Anna Vesaluoma

Introduction

This collaborative paper presents the first technical discussion of twentieth-century artist Annie Walke’s style and technique. It sheds light on Walke’s oeuvre, highlighting her contribution to the vibrant Cornish art scene. Annie Walke’s works were frequently exhibited and well-reviewed during her lifetime, and they are well appreciated in West Cornwall, yet she has received little scholarly attention. Her paintings merge a modern aesthetic with the depiction of religious themes or figures, often portrayed within an explicitly Cornish setting. Walke’s art reveals a unique and distinct viewpoint, which is further expressed in her poetry, published in two collections.1

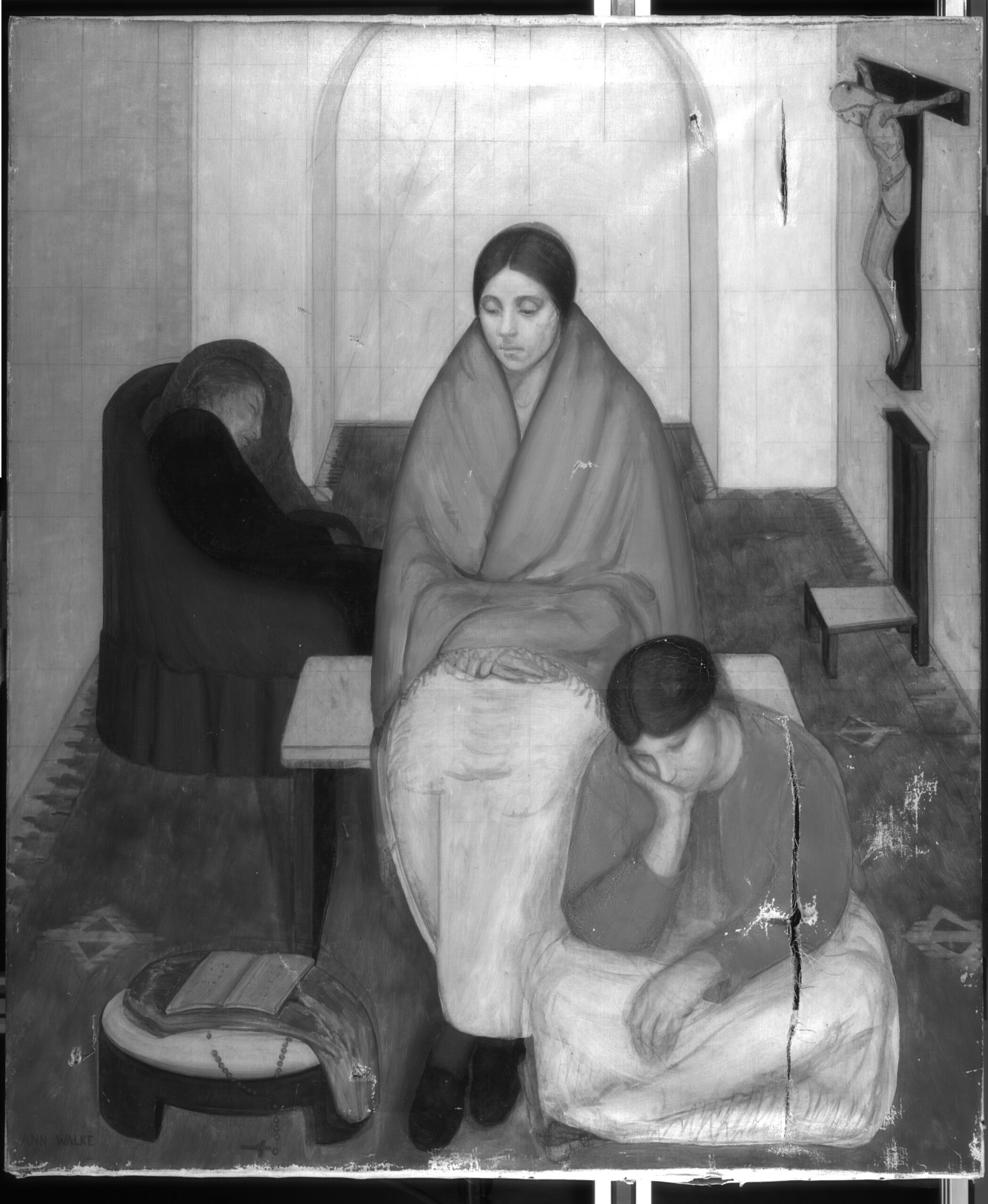

The present research collaboration began as an in-depth study undertaken on a painting by Walke titled Sorrowful Women (Fig. 1). This initial study led us to further investigate Walke’s practice. The article presents the outcomes of our art historical and archival research, as well as technical examination, enriched by findings from unpublished documentary sources, archived newspapers, and the rediscovery of previously unlocated artworks.

Annie Walke, née Fearon (Banstead, Surrey 1877–Mevagissey, Cornwall 1965), spent most of her artistic career in Cornwall, England, where she became affiliated with Lamorna school painters such as Dame Laura Knight (1877–1970) and Dod Procter (1890–1972).2 Prior to moving to Cornwall, Walke spent two years (1897–99) studying to become a pianist in Dresden, Germany, with her sister Hilda (who studied painting), and then trained as a painter in London at the Chelsea Art School, a private artistic studio co-founded in 1903 by the artists William Orpen (1878–1931) and Augustus John (1878–1961).3 The exact dates of Walke’s attendance are unknown, but the school closed down due to financial difficulties in 1907, and thus the artist must have studied there sometime between 1903 and 1907. Walke also attended the London School of Art, where she studied under Frank Brangwyn (1867–1956) and William Nicholson (1872–1949). There she met fellow artist Gladys Hynes (1888–1958), whose handwritten note to her brother Hugh, held in the Tate Archives, places Walke at the school around 1905.4 Walke must still have been studying at the London School of Art in 1908 since the art magazine Studio International documents her as having won fourth prize in the school’s competition for the best painted head that year.5 Walke’s sister Hilda is recorded to have been in St Ives, Cornwall, around 1900, and Walke followed her there soon after.6 Sometime before marrying Bernard Walke and adopting his name in 1911, Annie attended classes at the Cornish School of Landscape, Figure and Sea Painting.7 While her stays might have initially been seasonal, Walke ultimately settled in Cornwall sometime between 1911 and 1913, and stayed there for the remainder of her artistic career and life.8

Methodology

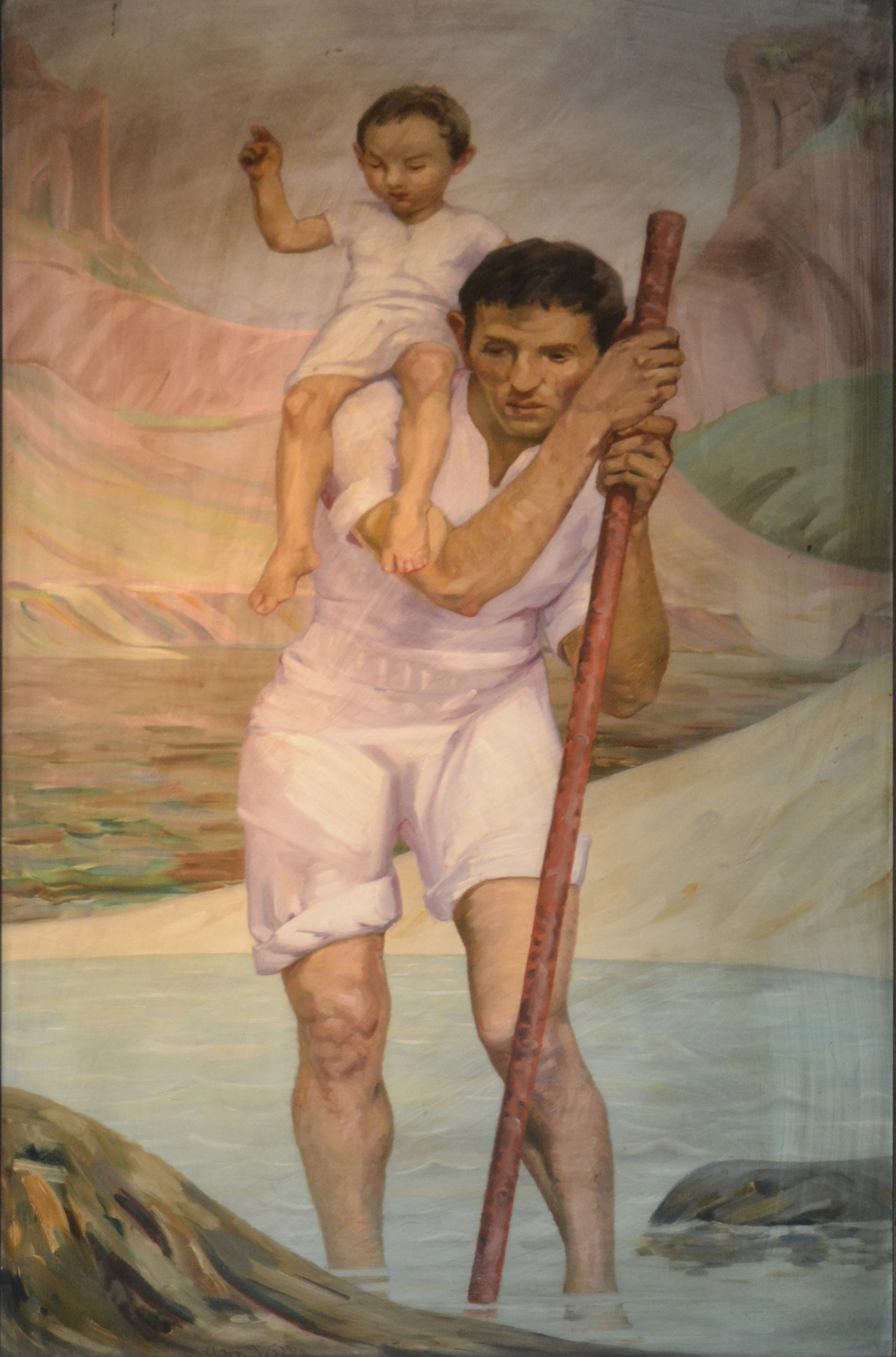

Annie Walke’s style and practice have not previously been the subject of a comprehensive study, and no catalogue of her work exists. In-depth technical analysis has been conducted on Sorrowful Women at the Courtauld Institute of Art.9 This painting belongs to a private collection and will be used as our principal reference to highlight aspects of the artist’s technique and compared with ten other paintings by Walke, examined in situ under visible light, ultraviolet light, and infrared reflectography. The other paintings analysed are mainly located in West Cornwall: in the Royal Cornwall Museum, Penlee House Gallery, Truro Cathedral, the former Penzance Girls’ School, and St Hilary Church. In 2018 we rediscovered a painting previously thought to be lost, St Christopher, at St Mary’s Church in Bourne Street, London (Fig. 2). Several other works were identified in auction catalogues, but this article will focus on paintings studied in person.

Establishing a chronology of Walke’s work has been particularly challenging, as most of her paintings are not dated. Paintings discussed here are collected in Appendix, which constitutes the first attempt at reconstructing a chronology of the artist’s works. Our hypotheses are based on close examinations of the artworks, style, and signatures, combined with the study of archival sources at the Newlyn Archive, St Hilary Archive, and Tate Archive. We structured a working timeline using the few dated works as markers and exhibition reviews as terminus ante quem. Exhibitions, however, were not considered to definitively signify a creation date since Walke would sometimes re-exhibit her work decades after its first display. For example, Bernard Walke and His Mother, first mentioned in a 1915 exhibition, was also exhibited in the St Ives Artists Spring Show of 1937.10 Nevertheless, exhibition reviews have allowed us to understand the generally positive reception of Walke’s paintings by contemporary critics and audiences, and beckons us to ask why her paintings have largely fallen into oblivion.

In addition to archival sources, our research builds on several published works. Bernard Walke’s autobiography, Twenty Years at St Hilary (1935), provides crucial information about the years 1913 to 1936, when Annie and Bernard Walke lived at St Hilary Church, near Marazion.11 Bernard Walke (1874–1941) was an eccentric vicar and a well-loved yet somewhat controversial figure in local history.12 The couple met in Polruan and married in 1911, after which they moved to St Hilary, where Bernard served as the parish vicar and Annie had an artist studio. In 2014, Christopher Garrett’s two-part article in the Lanteglos Parish News recorded biographical details about Annie Walke’s early life and her arrival in Cornwall in the early 1900s.13 Additional context is offered by scholarship on the artist colonies in Newlyn, West Cornwall, and St Ives, which have been widely researched.14 Philip Hills’s research, including his short book A Cornish Pageant (1999) and a pamphlet accompanying a 1997 exhibition he curated as a tribute to Annie and Bernard Walke, provides a wealth of biographical information and delightful anecdotes by those who knew the artist personally.15

While the available literature has been instrumental for contextualisation, this article is centred on object-based research following Annie Walke’s artistic process from her choice of support, through the paint layers, to the final signature placed on an artwork.

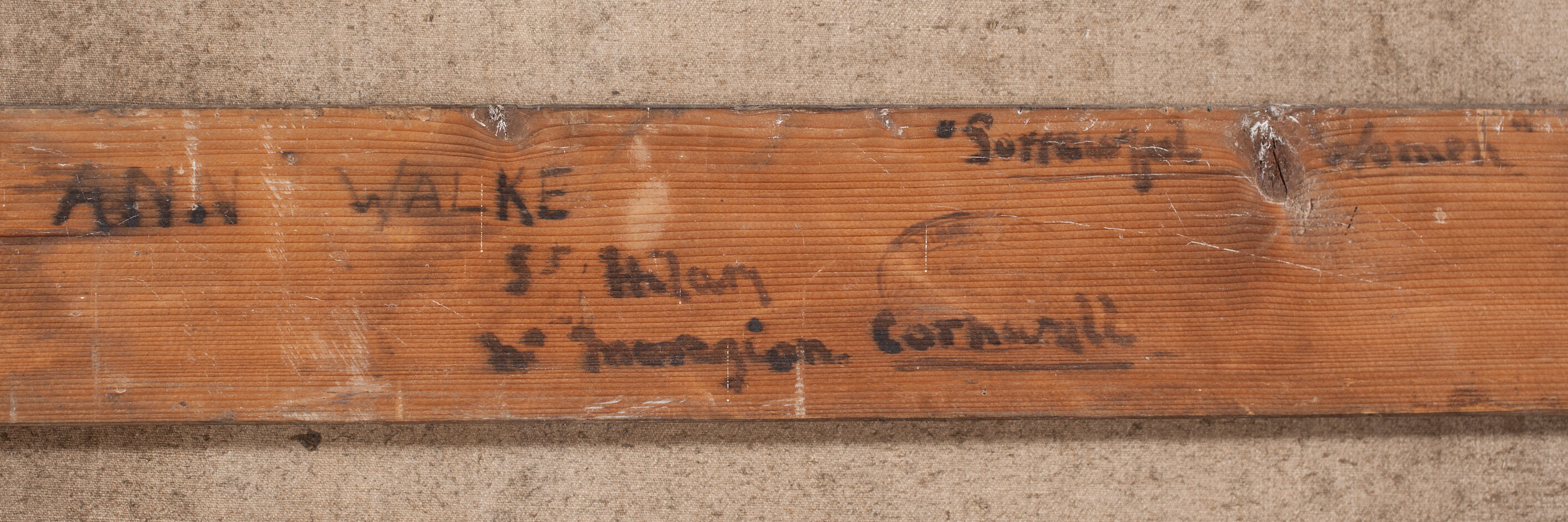

Supports

Annie Walke painted on both stretched canvas and rigid supports, such as panel and board. Her paintings range from as small as 5 x 8 cm16 to as large as 151 🞨 90.5 cm.17 Works on canvas include Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother, Christ Mocked, St Clare, St Joan, Virgin and Child, and St Christopher (St Mary’s, London). Sorrowful Women, one of the larger known paintings, is painted on commercially prepared twill-weave linen. The inscription in the artist’s handwriting on the stretcher bar confirms that the artwork was painted in St Hilary, hence dating it between 1913 and 1936 (Fig. 3).18 A stamp on the verso indicates that the canvas was prepared and primed by C. Roberson and Co., a well-known London-based supplier of artists’ materials. The specific trading name and address found in this stamp19 were in use between 1908 and 1937, a time period that overlaps with that of the painting’s execution, as established above.20 Annie Walke does not have a personal account documented in the Roberson ledger,21 but she could have bought the canvas directly from the shop on Long Acre street in London. Alternatively, she may have purchased the canvas through James Lanham, the principal supplier of artists’ materials in St Ives, Cornwall, who also operated a small gallery. There are two identical stamps on the stretcher bar of Sorrowful Women that read “James Lanham Ltd,” the name under which Lanham operated from 1907 onwards (Fig. 4).22 These Lanham stamps could indicate that the canvas was acquired from Lanham’s and/or that the painting was later exhibited at the shop. Lanham’s account with C. Roberson and Co. is recorded as active between 1898 and 1908.23 If Walke bought the canvas from Lanham, it would have been purchased in 1907–8, before she moved to St Hilary. It is also possible that Lanham retained old stock from Roberson & Co., even after the account was closed.

Lanham’s gallery, located on the same premises as the shop, was one of the main exhibition venues for artists from Newlyn and St Ives from 1887 until 1928.24 The artist and critic Norman Garstin, who Bernard Walke referred to as “my old friend,”25 called Lanham’s shop a “shoporium“ and described the gallery thus: “here, under an awning that softens the strong glare of the sky-light, you find a very charming little show, always fresh and interesting. Every month it is rearranged, new blood infused.”26 Unfortunately, no catalogues were printed for the frequently changing displays at Lanham’s.27 While there are no mentions of Walke exhibiting her paintings at Lanham’s, her sister Hilda Fearon is known to have unsuccessfully submitted work to the gallery,28 and as one of the most important and competitive venues for artists in the region to showcase their work, it is likely that Walke also would have attempted to show her paintings there. One of the two stamps sits underneath a label, handwritten by the artist, with information about the artwork; this strongly indicates the stamp to be a supplier’s stamp, rather than an exhibition-related stamp. As of 1928, when the St Ives Society of Artists (STISA) established the Porthmeor Gallery at 5 Porthmeor Studios, Lanham’s no longer served as the principal exhibition venue for local artists.29 Walke, who was a member of STISA from 1936 to 1951,30 exhibited Sorrowful Women in Porthmeor Gallery in 1936.31

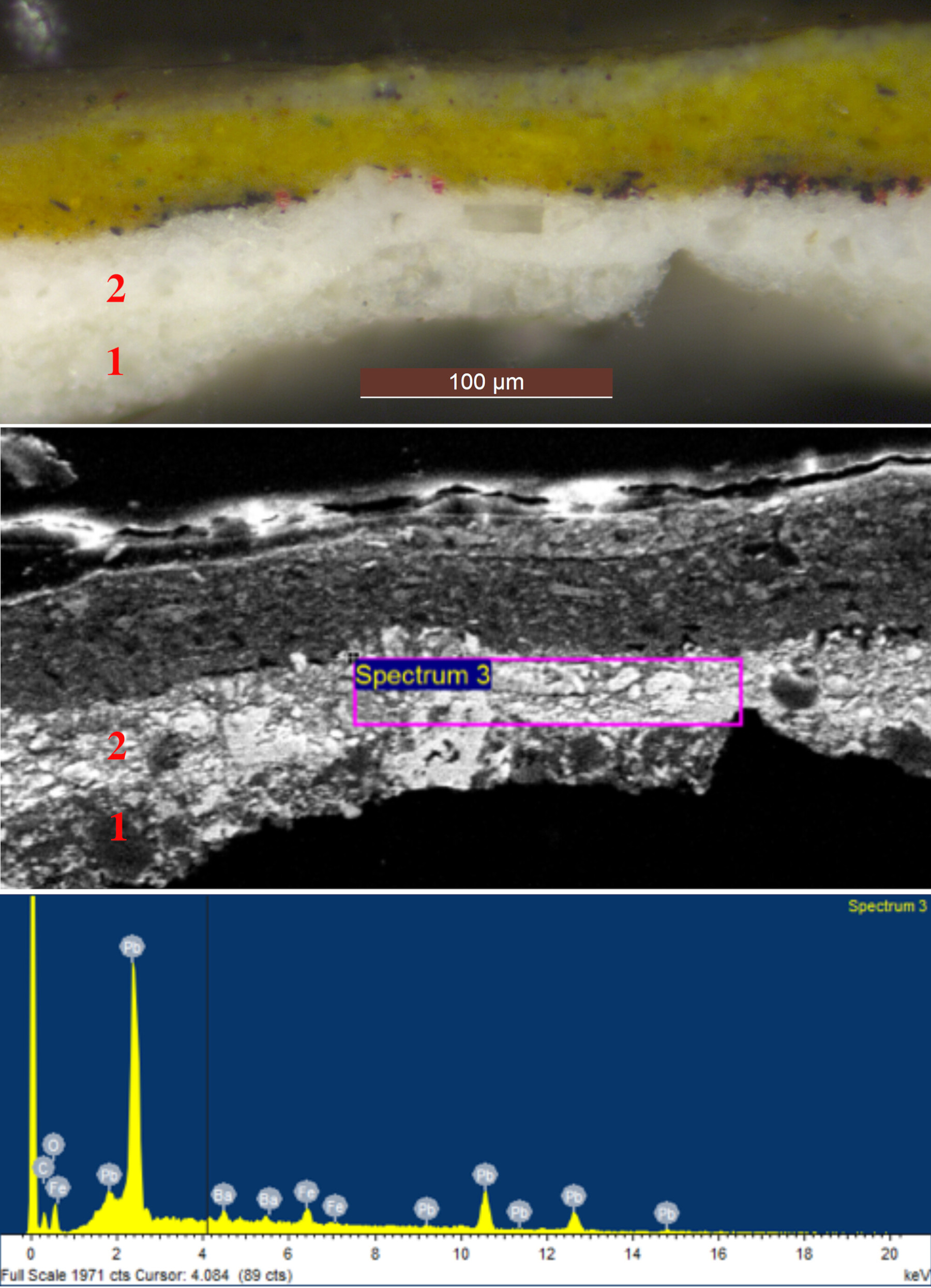

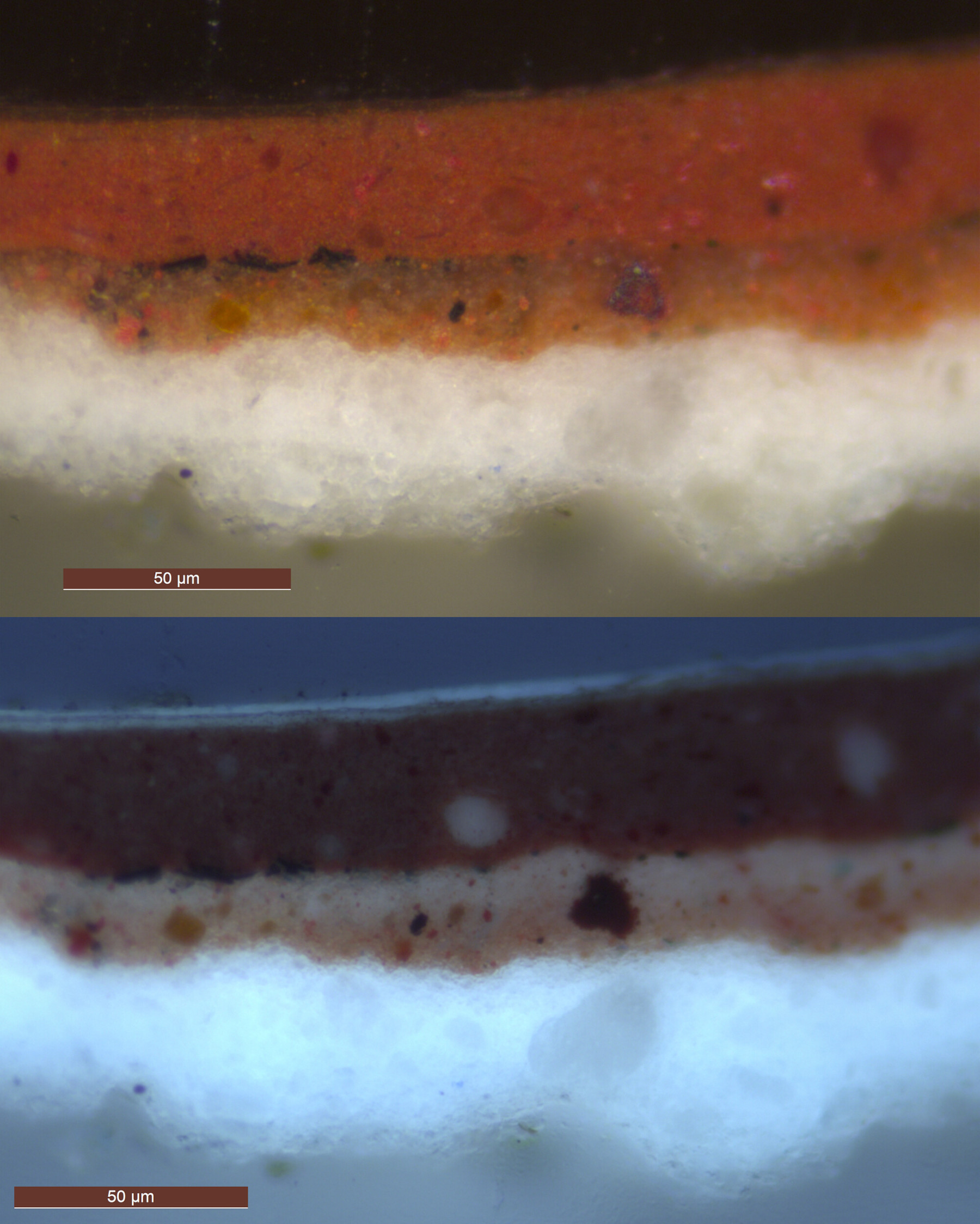

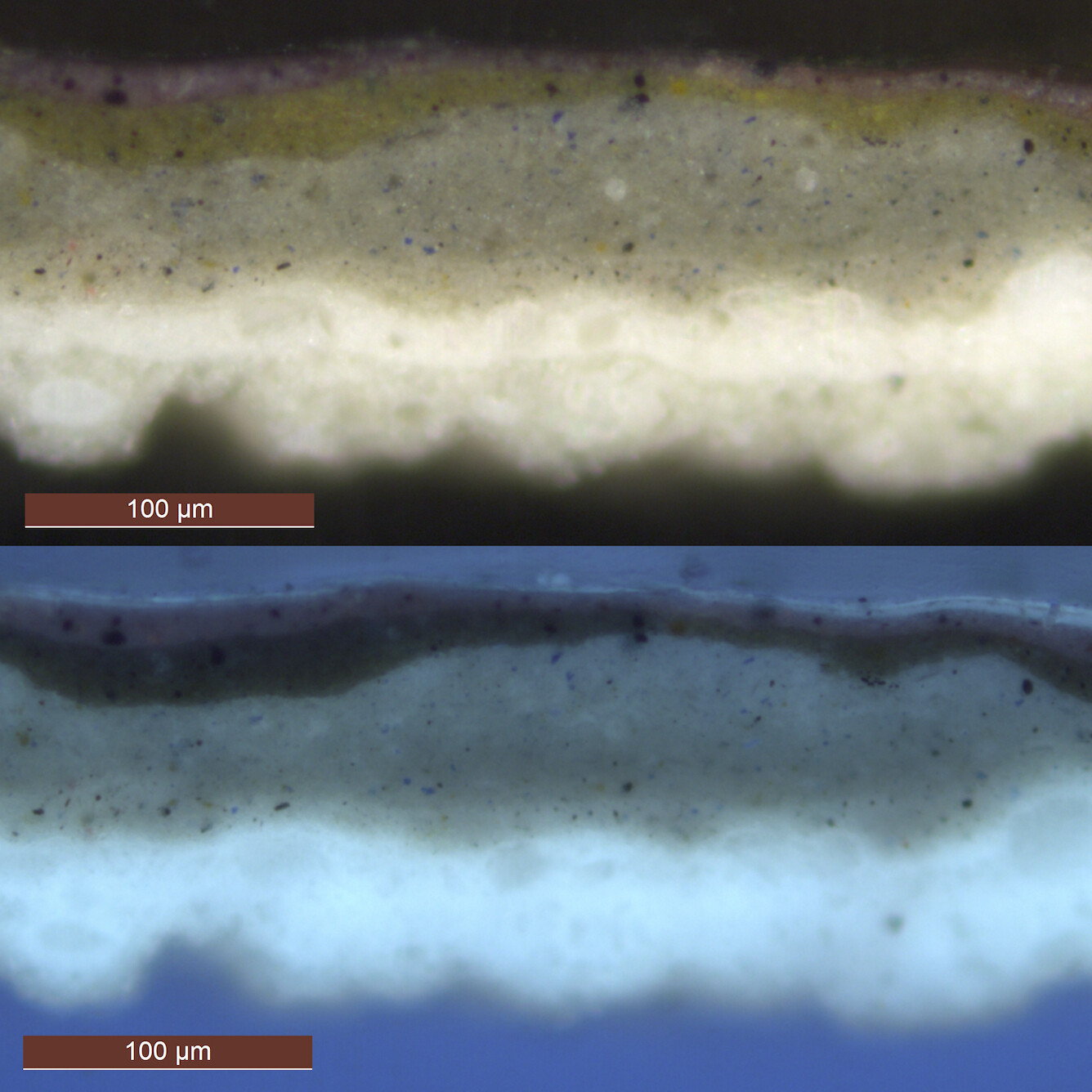

It seems that the twill support used for Sorrowful Women was uncommon in Walke’s practice; other paintings, including Virgin and Child and St Clare, are painted on tabby-weave canvas. The priming also varies across works; Walke seems to have purchased some commercially primed canvases, but physical evidence suggests that she also prepared some canvases herself. The verso of St Clare shows no canvas stamps and the white priming has visibly seeped through the weave, but it is clear that the canvas had been primed before it was tacked onto the wooden stretchers as the priming continues over the tacking edges and underneath the tacks. The priming on Sorrowful Women was applied on top of what is likely a cold size32 in two distinct layers composed of lead white and chalk, where the upper layer has a greater proportion of lead white.33 In some instances, Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)34 analysis of cross-sections also detected the presence of barium in the second layer, which could be indicative of barium sulphate, commonly added as an extender in commercially prepared grounds (Fig. 5).

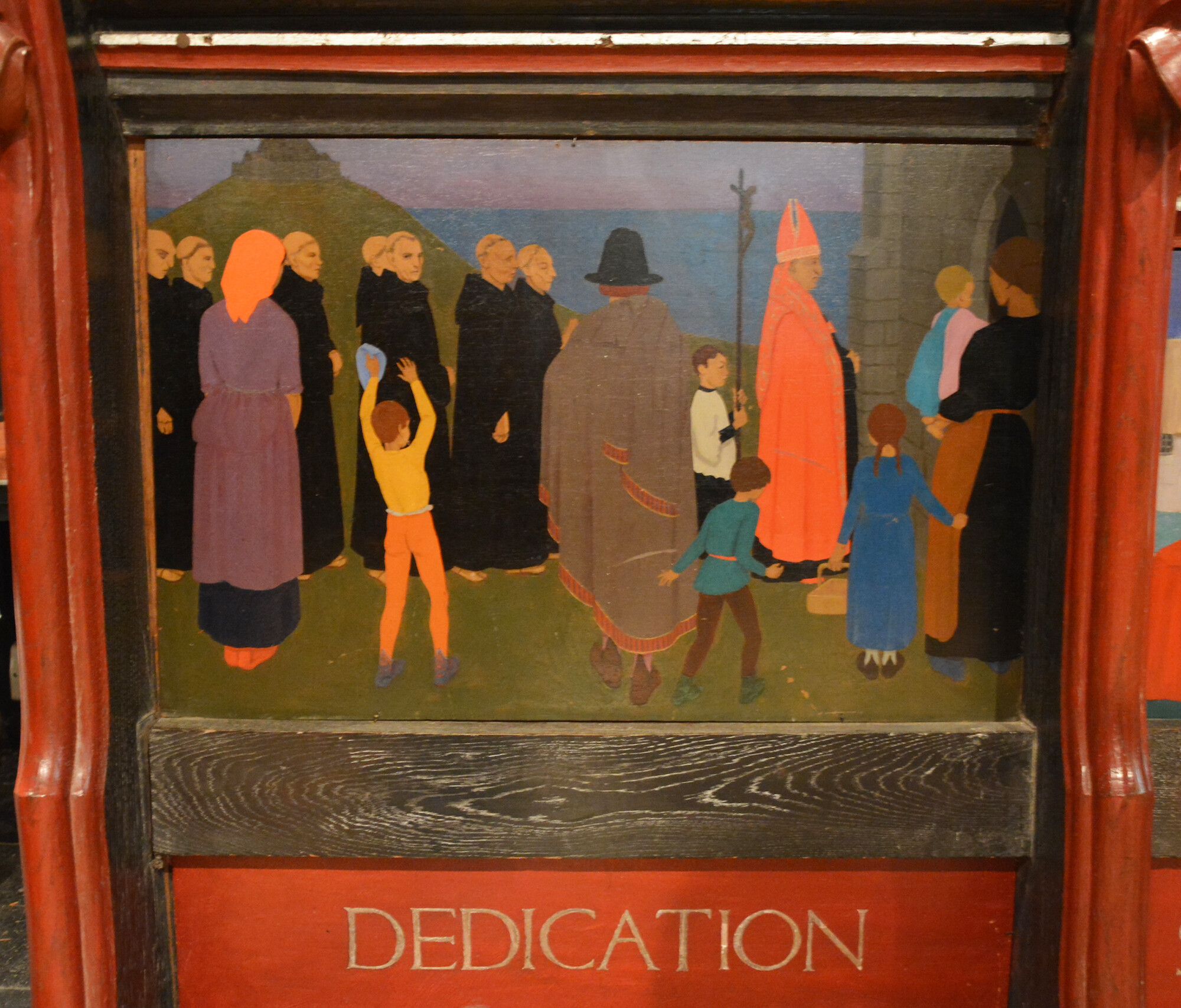

Walke’s paintings on rigid supports include Dedication and Christ Blessing Cornish Industry on wood panel, and Preaching from the Hill on hardboard.35 The decision to use panels for Dedication and Christ Blessing likely relates to the paintings’ specific commissions. Dedication decorates a wooden choir stall at St Hilary Church. Christ Blessing, created for Truro Cathedral, is a triptych set in an elaborately carved wooden frame. Its format, as well as use of gilding and pastiglia is inspired by traditional panel altarpieces. In contrast, the hardboard used for Preaching on the Hill is a cheaper alternative, suitable for a personal painting rather than an official commission.

Underdrawing

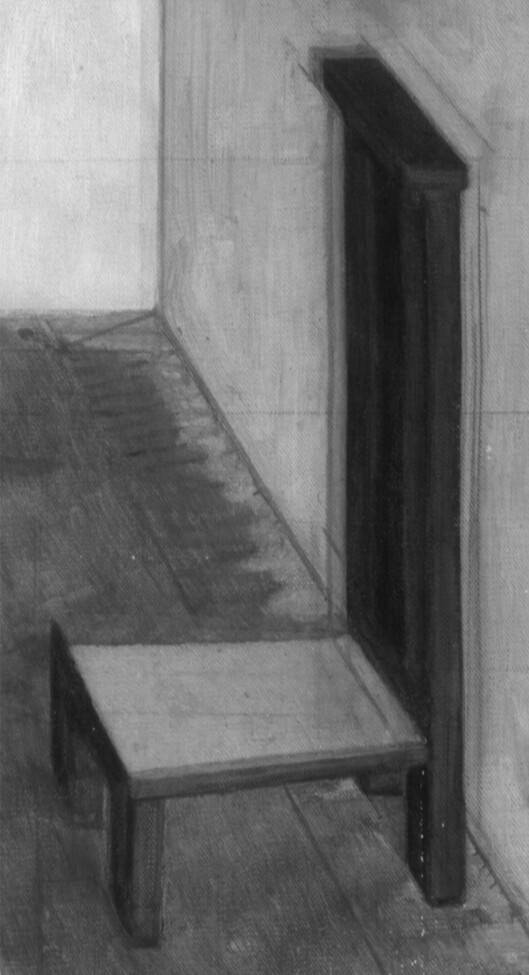

Infrared reflectography suggests the use of carbon-based underdrawing media. In Sorrowful Women, Walke used two different media for underdrawing: a dry medium to create straight lines and a wholescale grid structure, and a fluid medium applied with bolder and freer strokes for the figures (Fig. 6).36

The thin straight lines were used for the construction of the architectural space and working out the perspective. This grid may suggest the process of squaring up from a drawing, but unfortunately no surviving drawings by Annie Walke have been found. The use of a grid is a technique Walke could have learned through her artistic training. William Orpen, one of Walke’s instructors at the Chelsea Art School, used a grid in his underdrawing for squaring up, as demonstrated by Sally Taor’s research at The Courtauld.37 This grid seems similar to that employed by Walke. While squaring up was a standard practice at the time, it is likely that Walke would have picked up many similar, fundamental techniques during her formative years in art school, especially as she had only recently, upon the return from Dresden in 1899, abandoned the idea of becoming a pianist and chosen to study painting instead.

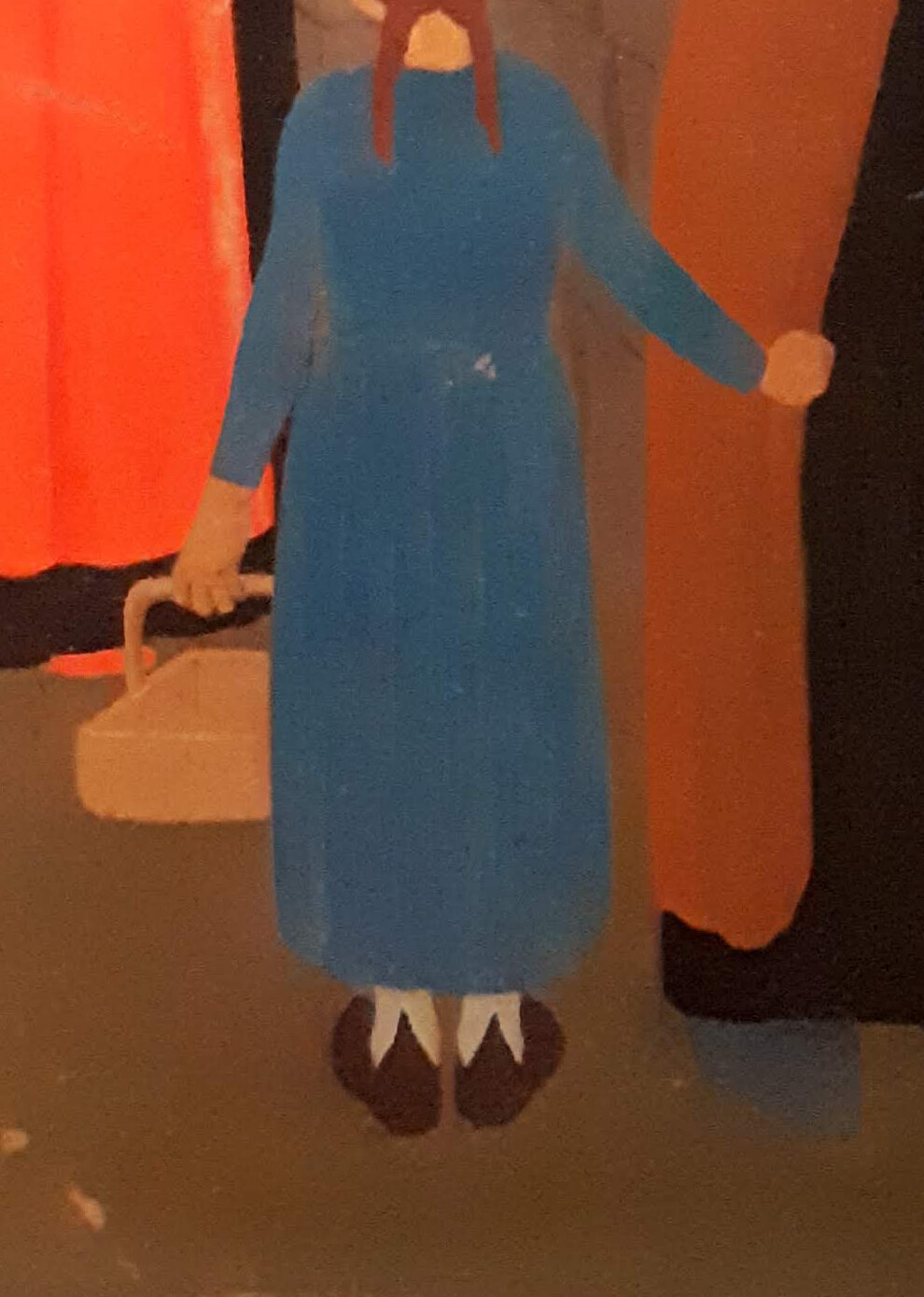

The second type of underdrawing consists of freehand lines of varying thickness and pressure in a fluid medium, possibly a thinned-down paint or ink, used to denote the positions and outlines of the figures. This carbon-based underdrawing medium is different from the black used in paint mixtures, which was identified through elemental analysis as bone black. One cross-section from the skirt of the seated figure on the right in Sorrowful Women shows the carbon-containing layer to be on top of a previously applied paint layer (Fig. 7). This suggests that the painting was reworked during the process of building up the composition. The numerous pentimenti, especially in the position of the sitting woman on the right, give a sense of the artist’s thought process. Walke sketched out the position of the legs underneath the skirt, possibly with the intention of achieving anatomical correctness – even though in the final painting the legs are hidden by the skirt – and an accurate portrayal of how the clothes drape over the limbs. Infrared reflectography of Dedication also reveals how the blue dress of the young girl was extended in the underdrawing (Figs. 8a, 8b).

Paint Layers

In addition to technical imaging, elemental analysis was carried out on Sorrowful Women and on cross-section samples from the painting.38 Technical examination reveals both a high level of planning but also a flexible approach, whereby the underdrawing was not always followed and alterations were made during the painting process. Careful planning of the principal compositional elements is evidenced, for example, in the reserve left for the red kneeling-stool in Sorrowful Women. This reserve is visible as a white square in infrared, while in normal light we can see how the artist painted the red over the grey floor to extend the stool and adjust its perspective (Figs. 9a, 9b). The X-radiograph of Sorrowful Woman shows an alteration in the light shape beneath the purple armchair to the left that does not correspond to its final shape (Fig. 10). A cross-section from the chair shows a series of grey and green layers underneath the uppermost visible purple paint, which is made of lead white, bone black, and red lake (Fig. 11).39 Perhaps the original shape of the chair is related to the green layer (bone black, chrome-based yellows, and iron earth pigments) beneath the purple, indicating the artist’s continuous rethinking of colour in the overall composition.

In Sorrowful Women, the paint was applied in relatively uniform thickness and often directly on the ground. This is the case in the turquoise background, composed of viridian, lead white, French ultramarine, and cobalt blue, which was brushed on with a large brush in dappled strokes. Similar bold brushwork is visible in the background of St Clare. The turquoise background in Sorrowful Women does not extend underneath the figures but was painted around and, in some places, over the figures. This can be observed in the hair of the central woman. Additionally, the edge of the turquoise shirt of the sitting woman has been refined by painting over the pink of the central woman’s skirt; the turquoise can be seen through the craquelure in the pink paint (Fig. 12). Walke created edges by painting with a loaded brush and pushing around the surrounding paint, forming fine ridges between the figure and the background. This technique of modifying edges is present across her paintings; for example in Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother, the background is painted over the elderly woman’s black shirt, which is visible through the craquelure. These ridges are also visible in paintings such as Sorrowful Women, St Clare, Christ Mocked, Preaching from the Hill (Fig. 13), and Christ Blessing Cornish Industry .

Figures and Subjects

Most of Annie Walke’s known works focus on the portrayal of people. Her paintings frequently feature Biblical figures such as Christ or the Virgin Mary, saints like Joan of Arc and Christopher, and figures referencing religious archetypes, as in Sorrowful Women.40 Despite Annie’s upbringing in a nonreligious home – some of her family members were even termed “active religious dissenters”41 – religion became an important part of her life after she met Bernard Walke, and in 1938 she officially became a Roman Catholic.42 Annie Walke was not, however, a typical vicar’s wife: she would slip into the back of the church for mass at the last minute43 and tore down the stables at St Hilary to convert them into a studio, an act that was met with some bitterness from the villagers.44 However, even after Bernard’s passing in 1941, religion persisted in her art and life. Richard Savage, who as a child in the mid-1950s used to stay with Annie Walke in Mevagissey, recalls that “[she] was always to be found at this time [each night around 11 pm] in her armchair and holding what I took to be a Bible or a prayer book.”45 In her poems, such as “The Grandmother” or “Jesus in the Workshop,” Walke writes from the first-person perspective as Jesus’s grandmother (St Anna) or as Jesus himself, situating herself within the imagined lived experience of these Biblical figures.46 While we have no examples of the artist talking about her artistic and literary work, Walke alludes to art itself being part of her religious practice, a way to reflect on religious figures and teachings. Most explicitly, in “Jesus in the Workshop,” Walke draws a parallel between the act of creating things and the act of praying, from which we might deduce that the artist considered her own art-making a form of prayer.47

Figures Technique

In Sorrowful Women and St Clare (Fig. 14), women are portrayed with similar soft and round facial characteristics, with the brush marks following the shape of the features. The modelling of the face of the central woman in Sorrowful Woman is done by first painting the darkest areas and shadows with iron earth pigments, and then building up the lighter areas and highlights with paint containing lead white; the darkest outlines are sometimes reinforced as the final touch. This buildup of paint is evidenced by the X-radiograph (Figs. 15a, 15b).

Conversely, St Joan and Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother are painted in a stylised and flat manner with crisp, dark outlines and a lack of modelling of light and shade (Fig. 16). Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother, signed “Ann Walke,” is presumed to have been painted between 1911, when the couple married, and 1915, when the work was exhibited at the Grosvenor Galleries.48 St Joan, commissioned for St Hilary Church, appears to be a companion piece to the 1920 painting St Francis by Roger Fry hanging in the same church, and thus we believe it to have been painted around the same time.

While the woman on the right in Christ Mocked is painted in a style comparable to Sorrowful Women and St Clare, Christ’s face and the woman’s hand are outlined in darker paint, making these stylistically closer to the treatment of faces in St Joan and Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother. With its three-dimensional modelling, St Clare was a commission for the chapel at the girls’ school in Penzance, renamed in 1928 the School of St Clare; while it is speculative to relate the commission to this change of name, it is unlikely that the painting was commissioned much earlier than this date (Fig. 17).49

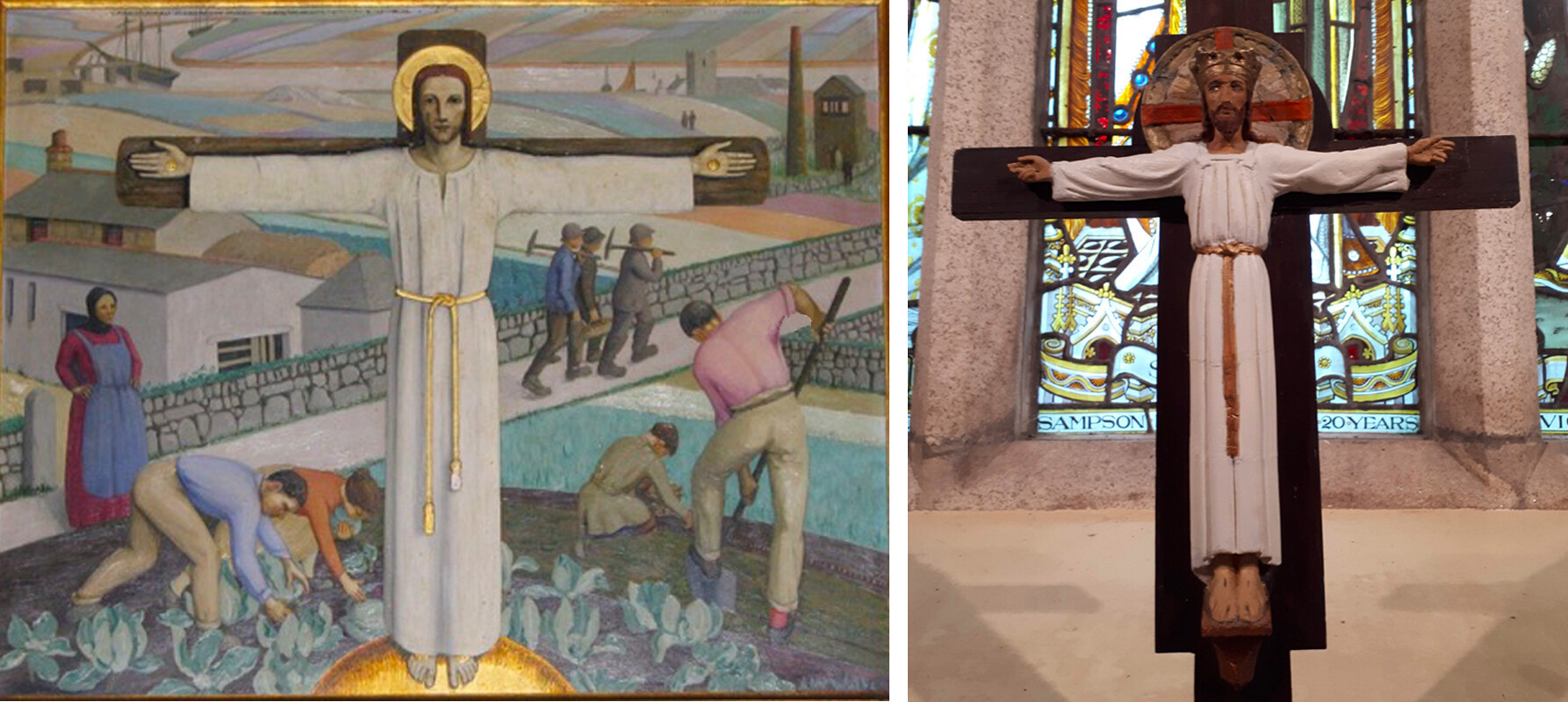

We believe the more graphic style to indicate the artist’s oeuvre before the mid-1920s, while the softer facial modelling is more frequent in what we believe to be later works – that is, after the mid-1920s. Thus, Christ Mocked may mark a transition between earlier and later works. The first known exhibition of Christ Mocked is in 1924 at the Goupil Gallery in London, establishing the painting’s terminus ante quem.50 The face of Christ also bears similarities to that of Christ in Christ Blessing Cornish Industry, commissioned by Bishop Frere for Truro Cathedral the year before, in 1923 (Fig. 17). The depiction of faces in Christ Mocked was frequently commented on – both positively and with criticism – by reviewers: The Cornishman declared that “Mrs. Walke’s Christ Mocked is excellent in every respect, Faces. . . That is the impression one carries away regarding it; faces of scorn and derision; faces bearing smiles of sinister amusement; faces and gestures that mock”51; but according to The Times “Mrs Walke has undoubtedly weakened her argument by jeering faces instead of relying upon the gestures which the dignity of her composition requires as the right expedient for illustration.”52 Of Christ Mocked, the Daily Mirror wrote: “Walke challenges accepted views on how the Saviour should be portrayed. She shows an ugly, haggard man, surrounded by young and old, who express contempt with pointing fingers and hands clasped in mimic prayer.“53 Despite the criticism, the painting remains one of Walke’s most exhibited artworks. In reference to its display at the Royal Institute Galleries in 1928, The Times noted that “[Walke’s] drawing has decision and the design is impressive even before you make out the subject”54; and an earlier review, of the Goupil Gallery’s 14th Salon, referred to the piece as “outstanding” and “not easily forgotten.”55 A St Ives Times review from 1936 defined the painting as “suggestive and much debated,” while the Cornishman called it “excellent, in every respect,” especially noting the portrayal of faces and the blending of colours.56

Hands, whether resting on the sitter’s lap or in gestures such as pointing or praying, are emphasised in Walke’s paintings as devices for expressing feelings. This is another relevant feature of Christ Mocked, but also especially evident in paintings such as Sorrowful Women, St Clare, and Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother. The positions of the hands in her paintings also show frequent alterations, either from the underdrawing to the paint layer or during the painting process, further highlighting the importance of hands for the artist.57 In 1964, towards the end of her life, Walke published a collection of her poems.58 In her texts, as in her paintings, Walke often spotlighted the hands of her characters, making these the focus of her compositions.59 In the poem “The Miracles of Healing,” hands are the vehicles for creation (“to shape the wood, the stone”), for emotion (“And to express many a tender thought”) and for healing (“From them the flames of healing fire . . . bringing sublimer gifts”).60

Models

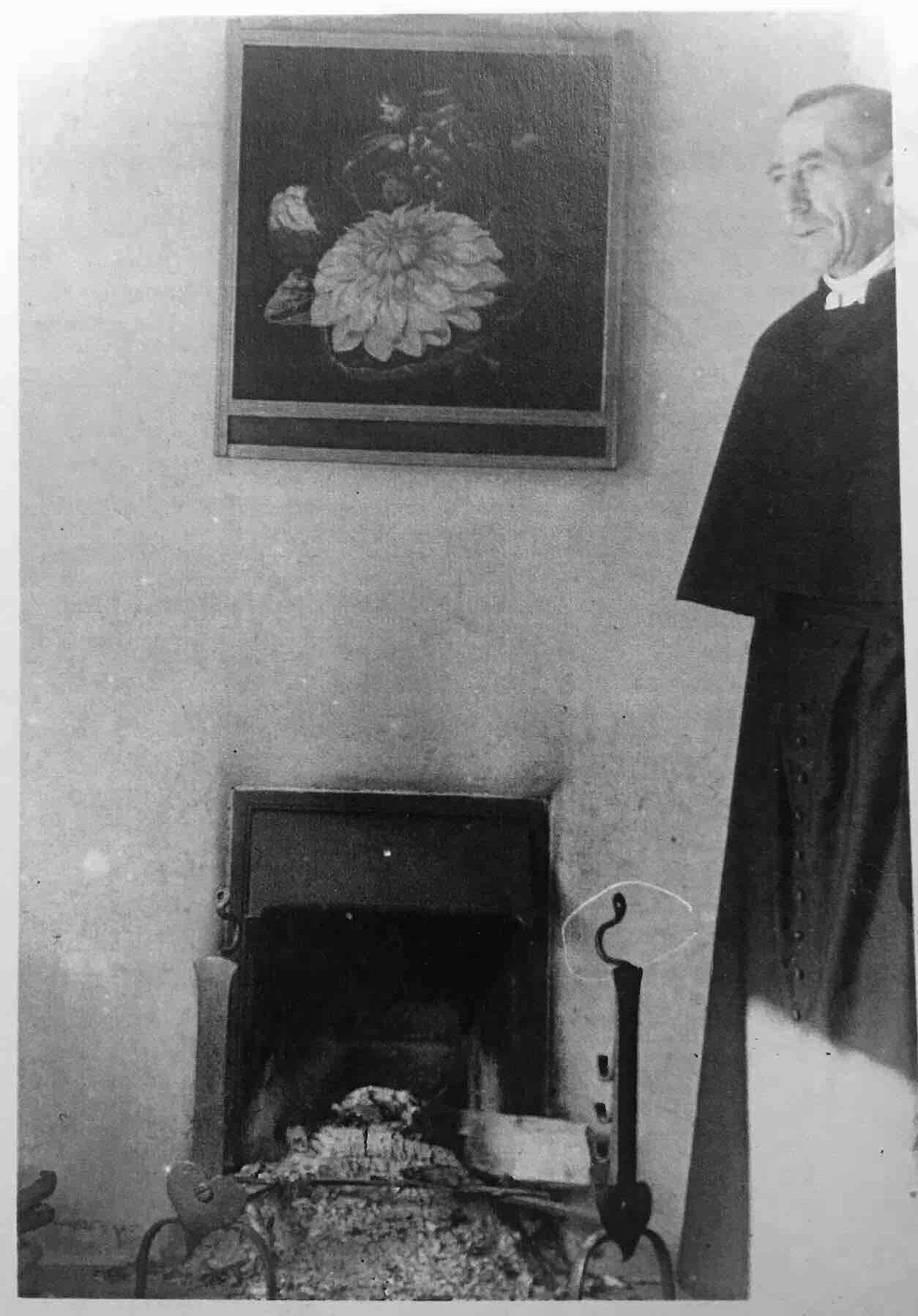

Even in her most mystical compositions, Walke’s paintings are often populated by individuals recognisable from her daily life who appear in explicit portraits or as as models for religious figures. Her husband, Bernard, was an easily accessible model who would frequently pose for the artist, an experience that he recalls in his 1935 memoir.61 Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother is an intimate portrayal of a familial relationship. A 1915 review of the spring exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery highlights the painting (then known as Mother and Son) as “remarkable in the sense of intimacy which it gives us through the stillness of the two figures.”62 This stillness of figures is prevalent across Walke’s works and creates a quasi-religious calmness especially in depictions of identifiable individuals as well as unidentified sitters, as in Sorrowful Women. In Portrait of a Gentleman in a Spanish Cloak, Walke portrays her husband in the couple’s residence at St Hilary, as we deduced from a photograph held in the St Hilary Archive which features Bernard Walke next to what appears to be the same fireplace as in the painting (Fig. 18). It is also possible that Annie Walke used this photograph, or another one taken at the same time, as reference material for the painting, while modifying elements, such as the still life hanging over the mantel into a mirror. In Dedication, Walke pictures her artist friend Dame Laura Knight, wearing her characteristic hat, as a figure in the crowd (Fig. 19). Additionally, it has been speculated that Walke’s close friend, painter Dod Procter, served as the model for her St Joan hanging in St Hilary Church.63

During her career, Walke had close relationships with many members of the variegated artistic community of West Cornwall. Her involvement with the Lamorna group is evidenced in her work, in written documents, and in letters exchanged between the artists. Walke and her husband were good friends with artist-couples such as Laura and Harold Knight, Dod and Ernest Procter, and Gertrude and Harold Harvey. All of these artists contributed to the new decorative scheme of St Hilary Church, an undertaking initiated by Bernard Walke in the 1920s.64 Annie and Bernard were first introduced to the Knights in 1915 by A. J. Munnings, although there is evidence that she had previously met Laura Knight at the Newlyn Show.65 Just as Walke records her eclectic and creative group of friends in her work, Laura Knight immortalised Annie and Bernard in two whimsical caricatures now at the Tate Archives.66 The account of St Hilary parish while Bernard Walke was in office is that of a prolific centre for artistic experimentation. Despite resistance from some locals, by the end of the 1920s, St Hilary had grown from a peripheral, countryside parish to become a lively creative community.67 At the heart of this community, the Walkes hosted parties, organised scenic processions, held tennis matches in the courtyard, and even staged theatrical plays.68 In the early 1930s, the modernist writer Mary Butts also entered this vibrant cultural scene along with her friend and colleague Frank Baker, who became the organist at St Hilary.69 This tight-knit community was as much about artistic exchange of ideas as about close friendships, as exemplified by the striking resemblance between Ernest Procter’s Crucifix for St Hilary Church, and Walke’s Christ Blessing at Truro Cathedral (Fig. 17).

Spatial Relationships and Settings

The figures in Walke’s paintings are hieratic apparitions, often superimposed on the background, lacking realistic spatial relationships with their surroundings. Despite the attention to perspective, evidenced in the underdrawing and architectural elements, even in paintings portraying indoor settings – including Sorrowful Women, St Clare, Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother, and Portrait of a Gentleman in a Spanish Cloak – the figures do not seem to be grounded in space. A delicate balance is needed for such static and detached figures to remain credible; while Walke mostly succeeds in keeping this balance, in some isolated instances her figures can appear clumsily floating in space. Perhaps it is this strange detachment between figures and space, done successfully, that prompted the Cornishman to note that “[the] composition [of Sorrowful Women] achieves much which does not at once meet the eye,” to the point that the reviewer speculates it would “probably be the most discussed picture” in the 1936 STISA autumn exhibition.70

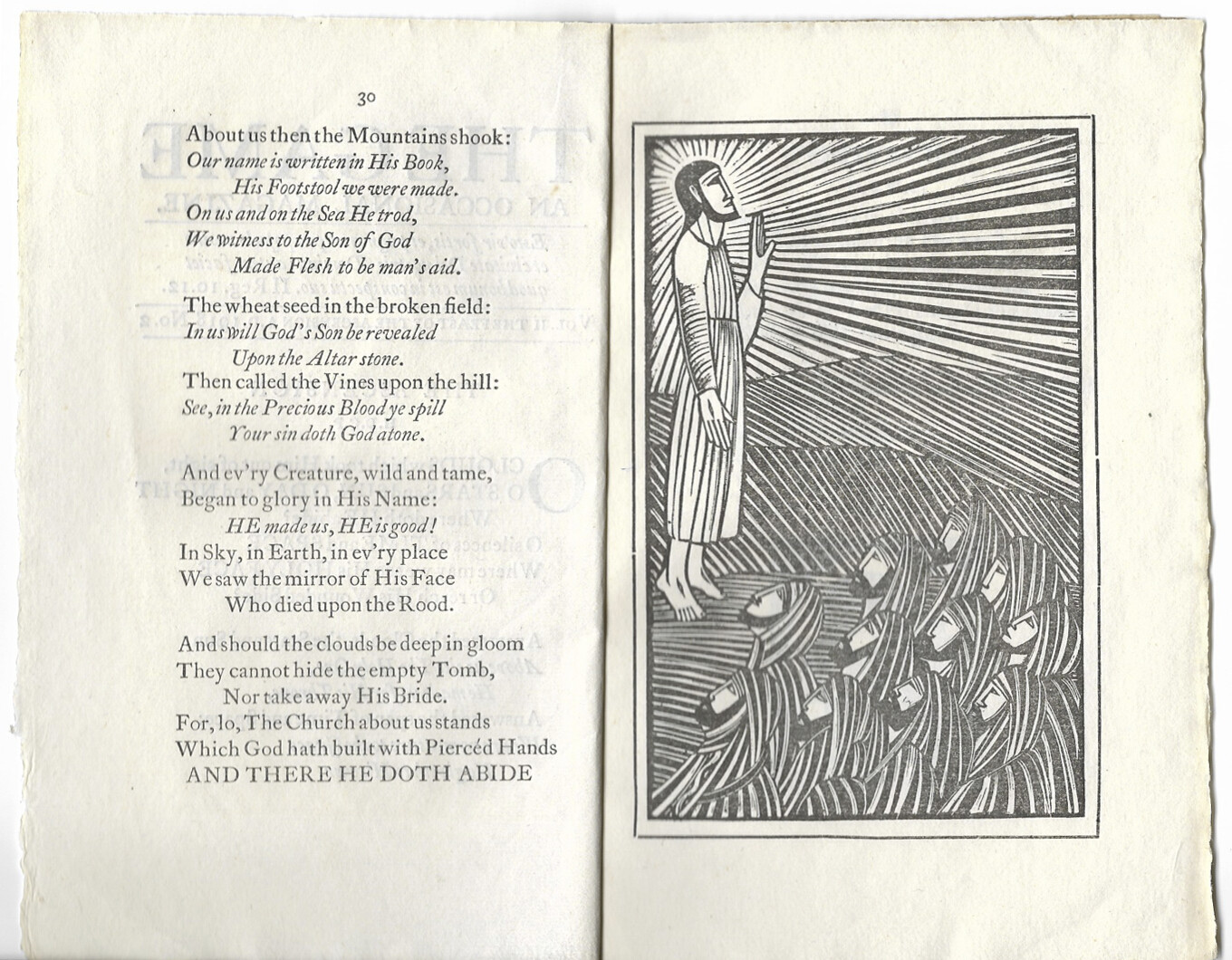

In most of the paintings, figures are contextualised within contemporary and recognisably Cornish landscapes. This is true for paintings depicting religious scenes, such as Christ Blessing Cornish Industry, Christ Mocked, Virgin and Child, St Joan, and Preaching from the Hill. According to Owen Baker at St Hilary Heritage Centre, Preaching from the Hill was probably influenced by a 1918 woodcut by Eric Gill in the Anglo-Catholic magazine The Game, to which the Walkes would probably have subscribed (Fig. 20).71 The painting represents the preaching of an unidentified biblical figure to a captivated crowd. While the subject matter remains ambiguous, not least due to different titles the artwork is known by,72 it is clear that the scene is set in a Cornish landscape. Weaving together everyday life and religion is characteristic of Annie Walke’s art and has been identified as a form of contextual theology.73 Thus, in Christ Blessing Cornish Industry, Christ on the cross is placed in front of a contemporary Cornish landscape populated by cabbage farmers and tin miners.74 This use of symbolic geography created an image that emanates a sense of Cornish pride for the members of the local parish to appreciate; the chapel where the triptych is located in Truro Cathedral is decorated with stained-glass windows showing scenes celebrating Cornish industries. Walke’s singular approach to religious scenes was valued by a local reviewer: “The picture is also in harmony with the windows [on] the west-end of the nave representing the angel who cared for fishermen and miners. It is an interesting mixture of realism and idealism and the scenery is painted by one who knows Cornwall well. The figure of the Redeemer is treated mystically. Altogether it is a very devotional as well as artistic piece of work.”75 Other reviews specifically commented on the meeting of technique and imagination in her paintings: the Cornish Guardian called Preaching from the Hill (there titled Angel of the Ascension) “a finely imaged and capably rendered work.”76 The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette commended Christ Mocked for its “treatment of a sacred subject in more modern style.”77 For her contemporaries, Walke’s works were about something greater than simply their visual aspect: “nearly always Mrs. Walke’s paintings suggest some quality or express some idea or belief greater than the picture.”78

Colour and Varnish

The unique colour palette, combining bright and pastel colours, adds to the mystical atmosphere in Walke’s works. Walke’s colour palette was made possible by the variety of pigments available in the first half of the twentieth century. She embraced the specific properties of colours such as the vivid blue tint of viridian, the bright opacity of vermilion, and the deepness of ultramarine, set against earthy colours and muted versions of these colours when mixed with white. Walke’s powerful choice of colours was noted at the time; in relation to the 1936 St Ives Society of Artists autumn exhibition, the Cornishman wrote: “Mrs Walke’s main contribution [to the exhibition], ‘Sorrowful Women’ is remarkable for its richness of colour and boldness of outline.”79 The use of blue, purple, and turquoise for the crop fields in her paintings is an imaginative capturing of the shades of the Cornish landscape, where fields of cabbage shine the brightest shades of green and turquoise under the summer sky. In Preaching from the Hill, the rolling hills alternate between bright orange, pastel blue, and light green, and in Virgin and Child, the grass is a startling turquoise. Walke used a similar turquoise green for some interior settings; in Sorrowful Women, this turquoise was identified as viridian using microscopy and elemental analysis.

As colour was a prime concern for the artist, the fact that Walke varnished her paintings speaks of her desire for well-saturated colours, but as many of her works were hung in churches, the varnish also acts as a layer of protection for the painted surface. In many of Walke’s paintings, the varnish covers the whole surface but is unevenly applied. This is demonstrated in the before-treatment ultraviolet fluorescence photograph of Sorrowful Women (Fig. 21). Similar uneven varnish was present in most of the paintings examined in situ with an ultraviolet light – St Clare, Preaching from the Hill, Christ Mocked, and Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother. Few of Walke’s paintings have undergone extensive conservation, and the uneven nature of the coating suggests that the varnish was most likely applied by the artist.80 In Sorrowful Women, the black dress of the elderly woman had a more liberally applied coating of varnish as indicated by the drips, probably applied for optimum saturation and to counter the effect of dark colours sinking in.

Signatures

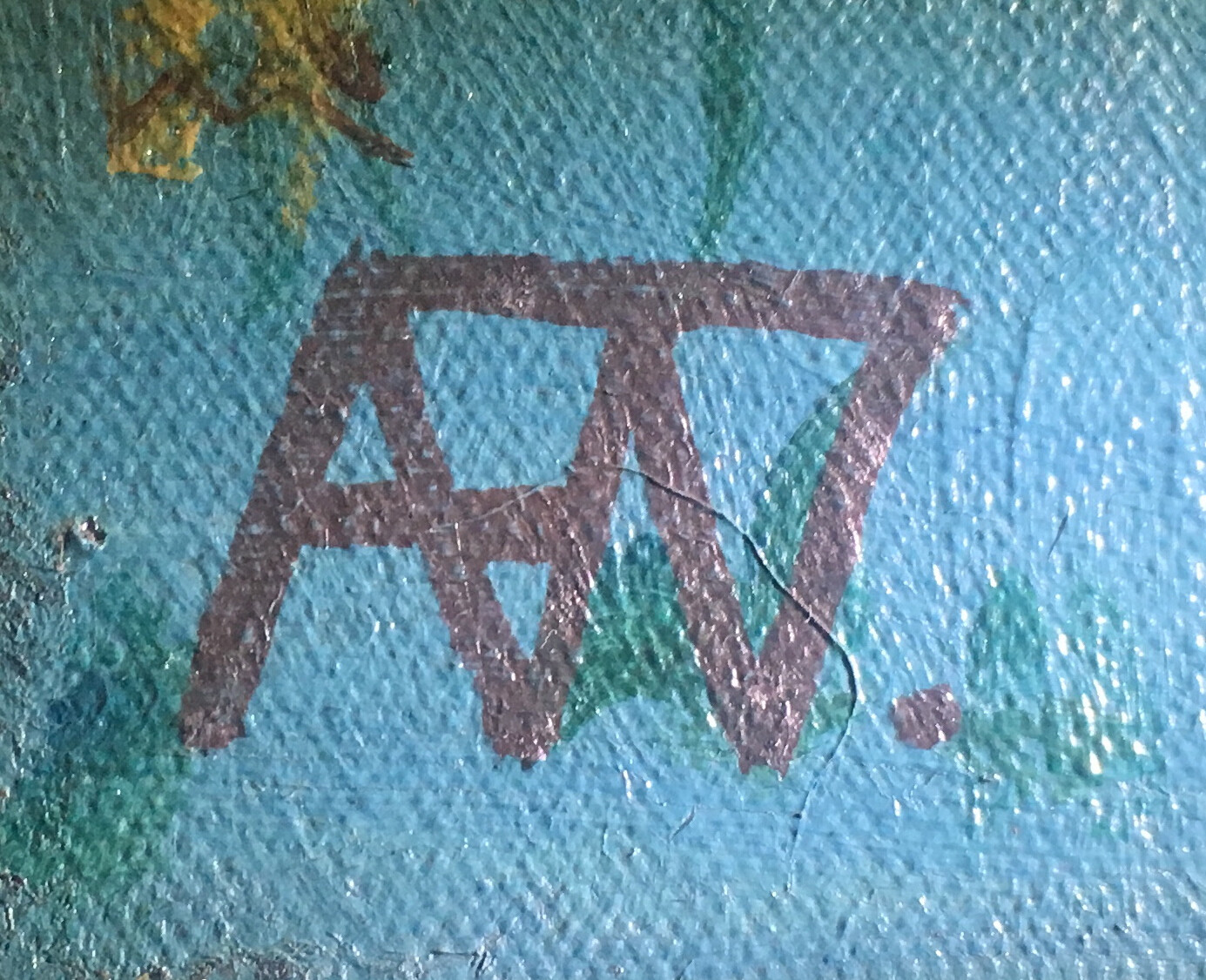

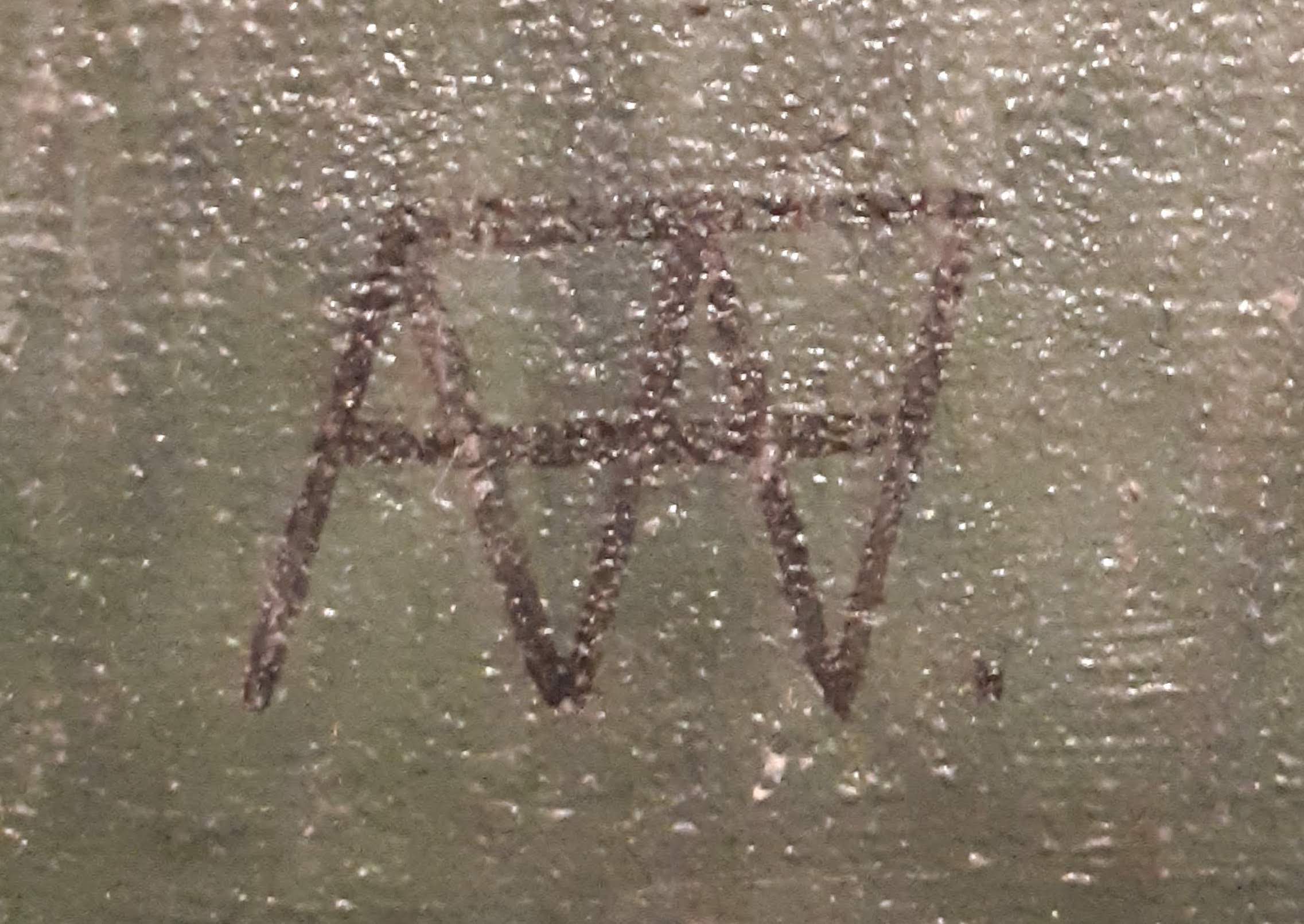

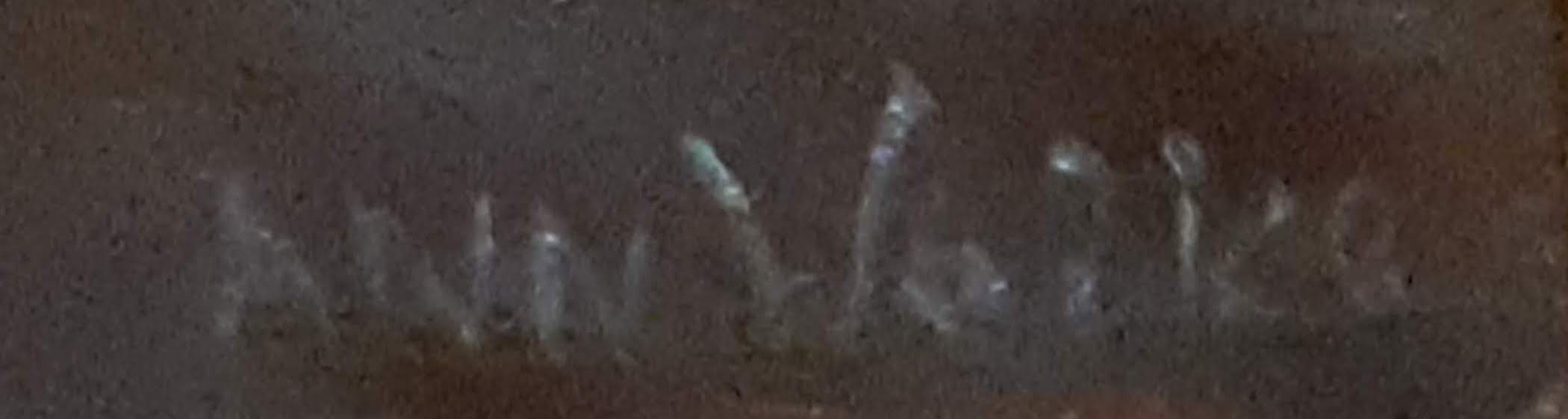

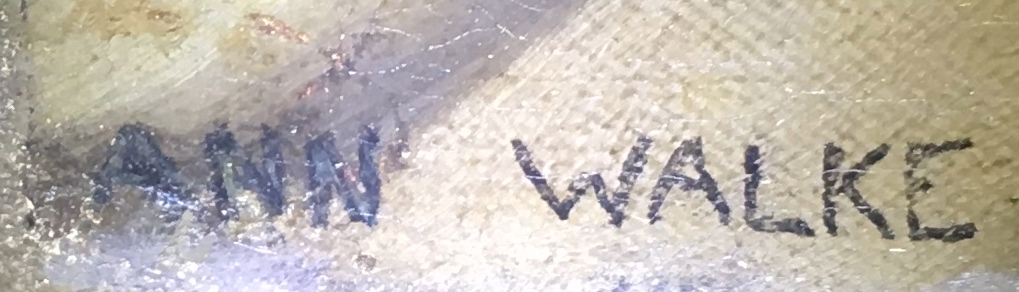

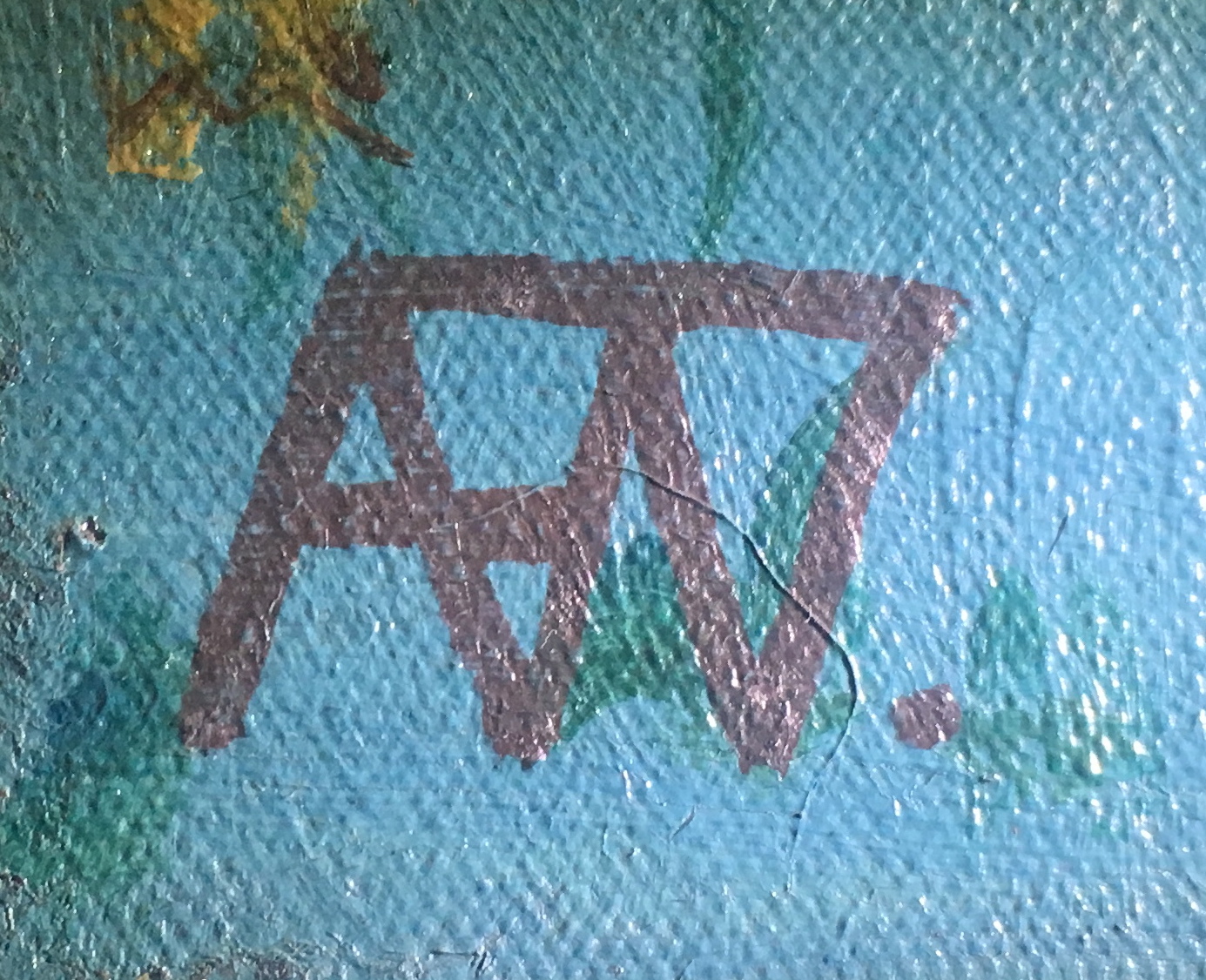

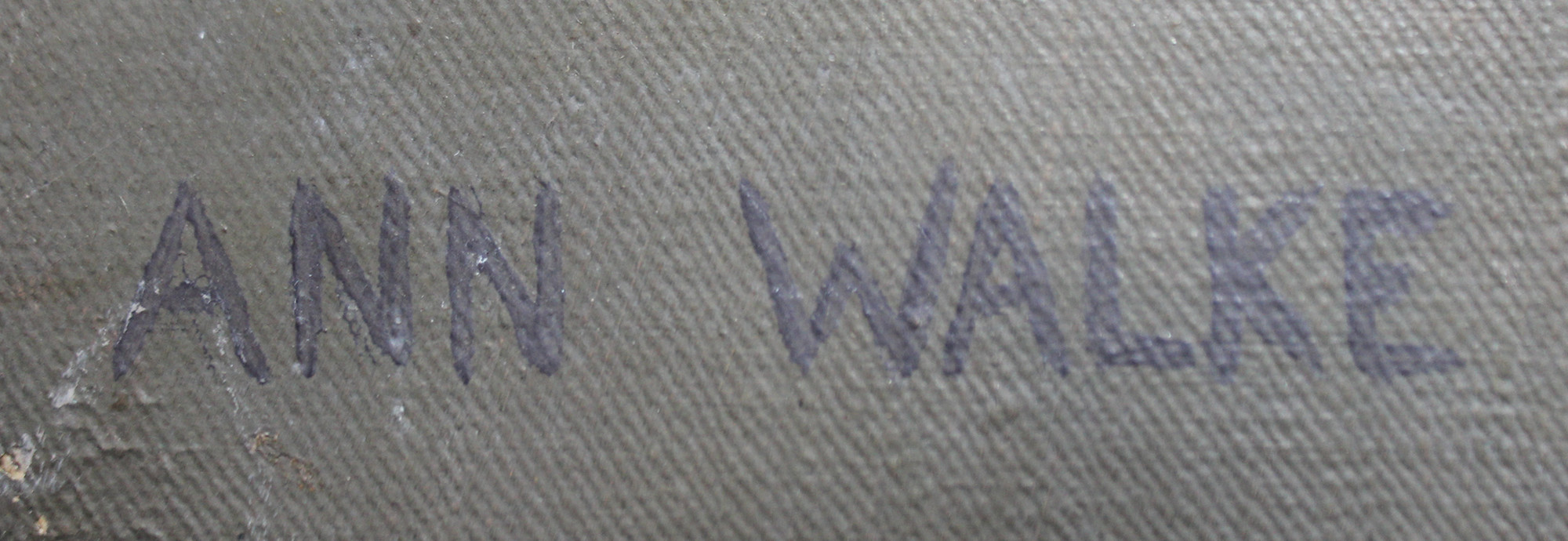

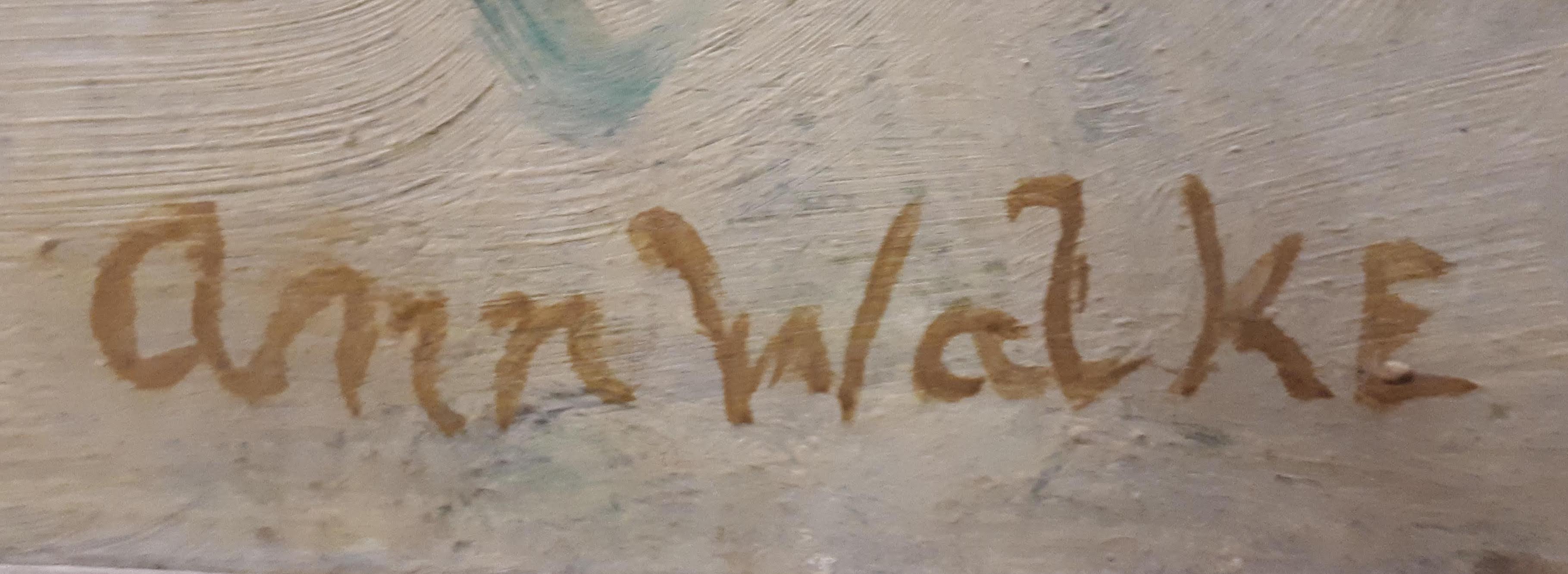

The artist was baptised as Annie Fearon and later became Annie Walke through her marriage, but she signed her works with different signatures and variations of her name. “Ann Walke” is the name she principally used to sign her works, while contemporary reviews often referred to her as “Mrs. Ann Fearon Walke,” stating her maiden as well as her married surname.81 However, rarely did the artist use both her maiden and married name in her signatures.82 In at least three instances, St Joan, Virgin and Child, and St Clare, Walke used the same monogram (AW) to sign her paintings (Fig. 22). The use of a monogram is a practice we encountered in St Hilary in works by other artists, such as Ernest Procter, and might have been common in that community of artist-friends.

Curiously, throughout their life together, Bernard Walke called his wife by her full name in an affectionate way, as he explained: “The name Annie by itself suggested her so little to me that I have never succeeded in calling her Annie. It has always been Annie Walke, and Annie Walke she must remain.”83

Conclusion

The technique evident in Walke’s paintings reveals a reflective and deliberate artist who paid great attention to composition, and was unafraid to use bold colours. This boldness in Walke’s works was acknowledged by national newspapers like The Times, which described her paintings as “memorable.”84 A review of one work noted a figure as emanating a “peculiar dignity,” yet another defining feature in Walke’s oeuvre.85 Elsewhere, Walke’s method is described as “quietly definitive.”86 It is precisely this quiet but confident quality which makes her paintings distinctive.

In many exhibition reviews, Walke’s works were considered the highlight or particularly memorable among the works exhibited.87 The most ravishing review she received was perhaps by the Pall Mall Gazette in 1923 when S. Kennedy North referred to her “brilliance that is unrecognised” in the title of a review of a group exhibition.88 The author ended the review with the reflection: “To my mind the work of Mrs. Ann Fearon Walke o’ertops the rest in her profound knowledge of form displayed in two portraits. I wonder when the Royal Academy will awaken to its duty in recognising the brilliance of this woman artist and her eminent sister of the brush, Mrs. Laura Knight?”89

Despite being included that same year among The Vote’s “leading women artists,”90 Annie Walke never received the acknowledgement called for in the Pall Mall Gazette. Why has she been overlooked in scholarly research? Despite the positive reception of her work, Walke seems to have been less involved in the London art scene than her peers active in Cornwall. For example, she appears not to have exhibited at the Royal Academy after 1910. This might have contributed to her works being understudied and, today, appreciated mostly by those who live in Cornwall. Other factors that may have contributed to her lack of recognition could be the subjects of her works, which are mainly religious, and her focus on a specifically Cornish setting. While it is true that most of Annie Walke’s known subjects are religious, our perception of her oeuvre might be skewed by the fact that we only studied works that are publicly accessible, a good portion of which were paintings in minor or provincial churches or chapels. Just a handful of her other works are in public collections, and these are all local to Cornwall.91 We suspect the remainder of her works to be in private collections, if not lost or destroyed.92 These “submerged” works, if traced, could contribute to a better and more exhaustive understanding of the painter’s oeuvre.

The purpose of the present study was to begin remedying the oblivion into which Walke seems to have fallen by providing the first art historical and technical discussion of this compelling female artist working in early twentieth-century Britain. As only one of Walke’s paintings has been thoroughly examined to date, in-depth technical research should be carried out on a larger selection of works. Conscious that our analysis represents a preliminary overview, we hope it will be a stepping-stone for further studies on Annie Walke.

Appendix. Paintings Studied

| Paintings (in estimated chronological order) | Signature | Exhibited | Other Information | Established or speculative (*) date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annie Walke, Reverend Bernard Walke and His Mother, undated. Oil on canvas, 182 x 121 cm. Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro | Anne Walke (capital “A”) | 1915 (Grosvenor Galleries), 1937 (Porthmeor Gallery) | Also known as Mother and Son; created between 1911 (when the couple married) and 1915 (its first exhibition). | 1911-15 |

| Annie Walke, St Joan, undated. Oil on canvas, dimensions unknown.. St Hilary Church, Cornwall. | AW (monogram) | Companion piece to St Francis by Roger Fry, dated 1920 | ca. 1920* | |

| Annie Walke, Dedication, undated. Oil on panel, 41.5 x 65.5 cm. St Hilary Church, Cornwall (Fig. 20) | No signature | Choir stall panels by other contributing artists were created ca. 1916–ca. mid-1920s. | 1920s?* | |

| Annie Walke, Christ Blessing Cornish Industry, 1923. Oil on panel, side panels: 75 cm x 24 cm, central panel: 75 cm x 95 cm. Truro Cathedral, Cornwall (Fig. 18) | ANN Walke | Commissioned by Bishop Frere in 1923; mentioned in Western Morning News (Plymouth), 29 December 1925 and 3 February 1926 | 1923 | |

| Annie Walke, Portrait of a Gentleman in a Spanish Cloak, undated. Oil on canvas, 127 x 101.5 cm. Private collection | Ann Walke (capital “A”) [no clear photograph is available] | 1937 (Bath’s Victoria Art Gallery) | Also known as Portrait of Bernard Walke standing three-quarter length and Portrait of Bernard Walke in Academic Robes. Painted in St Hilary, 1913–36. Bernard Walke visited Spain in 1923, possibly acquiring a robe there. | 1923*-27 |

| Annie Walke, Christ Mocked, undated. Oil on canvas, 91.5 x 79.2 cm. Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro | ANN WALKE | 1924 (Goupil Gallery, London), 1928 (Royal Institute Galleries), 1936 (Porthmeor Gallery, Birmingham, Cheltenham), 1937 (Bath’s Victoria Art Gallery), 1947 (Cardiff), 1949 (Swindon), 2003 (Penlee House) | Incorrectly dated ca. 1935 on ArtUK website | Before 1924 |

| Annie Walke, Virgin and Child, undated. Oil on canvas, dimensions unknown.. St Hilary Church, Cornwall. | AW (monogram) | Also known as Madonna with Red Shoes. Formerly hung in the School of St Clare, came to St Hilary possibly in the 1960s(?) | 1920s* | |

| Annie Walke, St Clare, undated. Oil on canvas, 151 x 90.5 cm. Former School of St Clare, Penzance, Cornwall (Fig. 15) | AW (monogram) | Penzance Girls’ School was renamed the School of St Clare in 1928. The chapel in which the painting hung was built in 1918. | ca. 1928* | |

| Annie Walke, Sorrowful Women, undated. Oil on canvas, 134.5 x 116 cm. Private collection (Fig. 1) | ANN WALKE | 1936 (Porthmeor Gallery) | Painted in St Hilary, 1913–36. | 1913-36 |

| Annie Walke, St Christopher, undated. Oil on canvas, dimensions unknown. St Mary’s Church, Bourne Street, London (Fig. 2). | Ann Walke (capital “A”) | Mentioned in a letter from Annie Walke to Mrs Rice, post-1936 (based on Walke’s address in the letter). The model for St Christopher was identified as Colin Summerfield on the cover of Hills, 2004. | ca. 1936?* | |

| Annie Walke, Preaching from the Hill, undated. Oil on hardboard, 81.5 x 53.5 cm. Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro, Cornwall | Ann Walke (capital “A”) | 1957 (St Austell) | Also known as Angel Appearing to Shepherds and likely the same as Angel of the Ascension. Eric Gill’s print published in The Game in 1918 was a possible source of inspiration. | 1918*-57 |

Acknowledgments

The research on Annie Walke begun as part of the “Painting Pairs” initiative at The Courtauld Institute of Art. We would like to thank all the people at The Courtauld who made the research collaboration possible, especially Dr Pia Gottschaller, Prof Aviva Burnstock, Dr Karen Serres, and Silvia Amato. We would like to extend our thanks to the owner of Sorrowful Women, who generously allowed us to study the painting. Conservation treatment of Sorrowful Women at The Courtauld was also supervised Maureen Cross, Pippa Balch and Clare Richardson. We are thankful for the help and support of numerous individuals, including Alison Smith, private conservator; Michael Harris, Royal Cornwall Museum; Owen and Carrie Baker, St Hilary; Reverend Rachel Monie, Colin Reid and Charles Butchart, Truro Cathedral; Katie Herbert, Penlee House; Helen Hoyle, Cornwall Artist Index; Pam Lomax and Newlyn Archives staff; Nicola Hemsley, Polwithen House; Dr Ben Blackburn and Bill Luckhurst, King’s College London; Kathy and staff, St Mary’s, Bourne Street, London; Darragh and Tate Archive Staff, Tate Britain. Our profound gratitude goes to Hugh and Jane Bedford, for their warmth and hospitality during our trip to Cornwall, and constant enthusiasm towards our research. Without them much of our work would not have been possible.

Authors’ Bios

Maria Vittoria Pellini holds a B.A. in Art History and Cultural Studies from Ca’ Foscari University (Venice) and an M.A. in Art History from The Courtauld Institute of Art (London), where she specialised in Italian Renaissance. She is currently based in Italy, where she completed a specialized Master in Arts Management and Administration at SDA Bocconi School of Management (Milan).

Anna Vesaluoma is a fellow in Paintings Conservation at the Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven, Connecticut), where she has worked since September 2020. She earned a B.A. (with Honors) in Painting from the University of Edinburgh and a Postgraduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings from The Courtauld Institute of Art (London). Her areas of interest include the materials and techniques of artists, and the structural conservation of paintings.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

104 Paintings in Exhibition at Wadebridge. Cornish Guardian. 29 August, 1957: 8.

Art Exhibitions. The Times. 13 February, 1928: 17. Available at The Times Digital Archive. (Accessed:14 Dec. 2018).

Art Exhibitions. The Times. 31 October, 1924: 15. Available at The Times Digital Archive. (Accessed: 14 Dec. 2018).

Art Exhibitions. The Times. 6 October, 1924: 17. Available at The Times Digital Archive. (Accessed:14 Dec. 2018).

Art School Notes” In Studio International 187, (January 1909): 77, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studio1909/0099 (Accessed: 30 Aug 2021).

Chapel for private devotion. Dedication at Truro Cathedral, Western Morning News (29 December 1925): 8.

Flower Paintings. Westminster Gazette. 12 March, 1923: 12.

Outstanding St. Ives Exhibition. Works By Five R.A.’s. Cornishman. 5 March 1936: 10, https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000331/19360305/102/0010 (Accessed: 14 Dec. 2018).

St. Austell will soon have an Arts Centre. Society acquisition made known at exhibition by newly-formed group. Cornish Guardian. 13 September, 1956: 8.

St. Ives Artists’ Spring Show. Cornishman. 15 April, 1937: 3, https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000331/19370415/020/0003 (Accessed: 14 Dec. 2018).

The International Society. The Spring Exhibition of the International Society (Grosvenor Galleries). Westminster Gazette. 19 May, 1915: 3-4, https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002947/19150519/003/0003 (Accessed: 14 Dec. 2018).

The International. Times. 11 May, 1915: 11. Available at the Times Digital Archive. (Accessed: 14 Dec. 2018).

The Vote Women at home and abroad. Women Artists, The Vote (27 April 1923): 3.

St Ives Society of Artists Spring Exhibition. St Ives Times. 3 March, 1936.

Works by Cornish Artists. Exhibition at Bath Art Gallery, Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette. 12 June, 1937: 10.

A Selection of Poems by the Artist Annie Walke (1877–1965), edited by Philip C. Hills, Camborne, Cornwall: Philip Hills, 2004.

Kennedy North, S. “The Art World Modern. Modern paintings equal to past masters. Mrs Fearon Walke: brilliance that is unrecognised.” Pall Mall Gazette. 16 March, 1923: 10.

Knight, Laura. 10 am 2 Queens Road (Drawing of Annie Walke), n.d., ink on paper, London, Tate Archives, in. nr. 895.4

Knight, Laura. Good Works (Drawing of Bernard Walke), n.d., ink on paper, London, Tate Archives, in. nr. 859.5.

Letter from Gladys Hynes to Hugh Hynes, 12 June c. 1905, inv. nr. 859.1, Tate Archives, London, England, UK.

Studio 8, no. 42, September, 1896: 242-244.

The Game 2, no. 2, 9 May, 1918.

The Year’s Art 1911: A Concise Epitome of all Matters Relating to the Arts of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and to the Schools of Design which have occurred during the year 1909, together with information respecting the events of the year 1911. edited by Albert Charles Robinson Carter. London, England: Hutchinson & Co., 1911.

The Year’s Art 1913: A Concise Epitome of all Matters Relating to the Arts of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and to the Schools of Design which have occurred during the year 1912, together with information respecting the events of the year 1913. edited by Albert Charles Robinson Carter. London, England: Hutchinson & Co., 1913.

The Year’s Art 1916: A Concise Epitome of all Matters Relating to the Arts of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and to the Schools of Design which have occurred during the year 1915, together with information respecting the events of the year 1916. edited by Albert Charles Robinson Carter. London, England: Hutchinson & Co., 1916.

The Year’s Art 1922: A Concise Epitome of all Matters Relating to the Arts of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and to the Schools of Design which have occurred during the year 1921, together with information respecting the events of the year 1922. edited by Albert Charles Robinson Carter. London, England: Hutchinson & Co., 1922.

Walke, Annie. A Boy Returns: and other poems. Haywards Heath, Sussex: Breakthru Publications 1964.

Walke, Bernard. Twenty Years at St. Hilary. Saint Agnes: Truran, 1935.

Secondary Sources

“Annie Walke.” In Cornwall Artist Index (n.d.), https://cornwallartists.org/cornwall-artists/annie-walke (Accessed: 29 Dec 2018).

“James Lanham & Co.” In Cornwall Artist Index (n.d.), https://cornwallartists.org/cornwall-artists/james-lanham-co (Accessed: 29 Dec 2018).

“St Hilary, St Hilary.” In Cornwall Historic Churches Trust Website. n.d., https://www.chct.info/histories/st-hilary-st-hilary/ (Accessed: 29 Dec 2018).

100 years in Newlyn: Diary of a gallery, edited by Melissa Hardie. Penzance: The Patten Press, 1995.

Allchin, Donald. Bernard Walke: A Good Man Who Could Never be Dull. Abergavenny: Three Peaks Press, 2000.

Cross, Tom. The Shining Sands: Artists in Newlyn and St Ives 1880 -1930. Devon: Westcountry Books, 1994.

Fox, Caroline and Francis Greenacre. Painting in Newlyn 1880-1930. (Exhibition Catalogue: London 11 July-1 September 1985, London: Barbican Art Gallery), London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1985.

Garrett, Christopher. “The Artist Annie Walke (nee Fearon) – To Polruan – Part 1.” Lanteglos Parish News, (October-November 2014): 18.

Garrett, Christopher. “The Artist Annie Walke (nee Fearon) – To Polruan – Part 2.” Lanteglos Parish News, (December 2014 – January 2015): 18.

Hackney, Stephen. On Canvas: Preserving the Structure of Paintings. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2020.

Hardie, Melissa. Artists in Newlyn and West Cornwall, 1880-1940: A Dictionary and Source Book. Bristol: Art Dictionaries Ltd, 2009.

Hedley, Gerry. “The Practicalities of the Interaction of Moisture with Oil Paintings on Canvas”. In Measured Opinions. London: United Kingdom Institute of Conservators, 1993: 112-122.

Hills, Philip C. A Cornish Pageant. Camborne, Cornwall: Philip Hills, 1999.

Hills, Philip C. Bring Back the Donkeys: A Tribute to Father Bernard Walke and the Artist Annie Walke. Covering the Years 1870-1965 (Exhibition Booklet: Jesus Chapel, Truro Cathedral, 18 Dec 1997-2 Jan 1998), Truro: Philip Hills, 1997.

Holroyd, Michael. “John, Augustus Edwin (1878-1961).” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/34196 (Accessed: 17 May 2019)

Knight, Laura. Oil Paint and Grease Paint: Autobiography of Laura Knight. London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson Limited, 1936.

Knight, Laura. Oil Paint and Grease Paint: Autobiography of Laura Knight. London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson Limited, 1936.

Matless, David. “A geography of ghosts: the spectral landscapes of Mary Butts.” Cultural Geographies 15, no. 3 (Jul 2008): 335-357, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1474474008091331.

Pellini, Maria Vittoria and Anna Vesaluoma. “Threads coming together. A study of Sorrowful Women by Annie Walke.” In The Courtauld Institute of Art Website. https://courtauld.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sorrowful-Women-by-Annie-Walke.pdf, 2019.

Rachel Monie “God, Beauty and Imagination Assignment”. Unpublished essay (2018).

Simon, Jacob. “British Art Suppliers, 1650-1950 – L.” In National Portrait Gallery Website. 2018, https://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/directory-of-suppliers/l (Accessed: 29 Dec 2018).

Simon, Jacob. “British Art Suppliers, 1650-1950 – R.” In National Portrait Gallery Website. 2018, https://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/directory-of-suppliers/r.php (Accessed: 29 Dec 2018).

Simon, Jacob. “Charles Roberson & Co.” In British canvas, stretcher and panel suppliers’ marks VIII, 2017, https://www.npg.org.uk/assets/files/pdf/research/artists_materials_8_Roberson.pdf (Accessed: 29 Dec 2018).

Taor, Sally. “The painting materials and techniques of William Orpen RA 1878-1931.” Third Year Project MA Conservation and Technology: The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2006, unpublished.

Tovey, David. Creating a Splash: The St Ives Society of Artists. The first 25 years (1927-1952). (Exhibition Catalogue: 21 June 2003-30 August 2003, Penzance: Penlee House Gallery and Museum; 15 May 2004-10 July 2004, Newport: Newport Museum and Art Gallery) Tewkesbury: Wilson Books, 2003.

Tovey, David. St Ives (1860-1930): The Artists and the Community. A Social History. Tewkesbury: Wilson Books, 2009.

Whybrow, Marion and David Brown. St. Ives,1883-1993: Portrait of an Art Colony. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1994.

Woodcock, Sally and Judith Churchman. Index of account holders in the Roberson Archive 1820-1939. Cambridge: Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge, 1997.

Notes

Annie Walke, A Boy Returns, and Other Poems (Haywards Heath, Sussex: Breakthru, 1964); A Selection of Poems by the Artist Annie Walke, ed. Philip C. Hills (Camborne, Cornwall: Philip Hills, 2004). ↩︎

Basic information on the artist can be found in the Cornwall Artist Index, s.v., “Annie Walke,” https://cornwallartists.org/. ↩︎

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2006), s.v., “John, Augustus Edwin (1878–1961),“ by Michael Holroyd. The Chelsea Art School, a private teaching studio located at nos. 4 and 5 Rossetti Studios, Flood Street, Chelsea, is not to be confused with the better-known Chelsea School of Art, later Chelsea College of Art, which – despite the similar names – was an entirely different institution. ↩︎

Gladys Hynes to Hugh Hynes, 12 June [c. 1905], Tate Archives, London, 859.1. On the back of the letter, Hugh Hynes noted 1905 as an indicative date. ↩︎

“Art School Notes,” Studio International 187 (October 1908): 77. ↩︎

Christopher Garrett, “The Artist Annie Walke (nee Fearon) – To Polruan – Part 2,” Lanteglos Parish News, December 2014–January 2015: 18. ↩︎

Melissa Hardie, Artists in Newlyn and West Cornwall, 1880–1940: Dictionary and Source Book (Bristol: Art Dictionaries, 2009), 81. ↩︎

Walke’s address is recorded first as “1A Carlyle-studios, King’s rd, Chelsea, S.W.,” in The Year’s Art, 1911: A Concise Epitome of all Matters Relating to the Arts of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and to the Schools of Design which have occurred during the year 1910, together with information respecting the events of the year 1911, ed. Albert C. R. Carter (London: Hutchinson, 1911, 471; and later as “Polruan, near Fowey, Cornwall,” in The Year’s Art, 1913 . . ., ed. Carter (London: Hutchinson, 1913), 562. ↩︎

Maria Vittoria Pellini and Anna Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together: A Study of Sorrowful Women by Annie Walke” (2019), https://courtauld.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sorrowful-Women-by-Annie-Walke.pdf. ↩︎

See “The International Society. The Spring Exhibition of the International Society (Grosvenor Galleries),” Westminster Gazette, 19 May 1915: 3–4; “The International,” The Times (London), 11 May 1915: 11; and “St. Ives Artists’ Spring Show,” Cornishman (Penzance), 15 April 1937: 3. In the Westminster Gazette, the artwork was titled “Mother and Son,” but the 1937 review describes “Mother and Son” as a portrayal of Bernard Walke and his mother, thus indicating the artwork is the same as the Royal Cornwall Museum picture. ↩︎

Bernard Walke, Twenty Years at St Hilary (Truro, Cornwall: Truran, 1935). ↩︎

For more on Bernard Walke, see Donald Allchin, Bernard Walke: A Good Man Who Could Never Be Dull (Abergavenny: Three Peaks, 2000); and Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 4–6. ↩︎

Part 2 was published in 2015. Christopher Garrett, “The Artist Annie Walke (nee Fearon) – To Polruan – Part 1,” Lanteglos Parish News, October–November 2014: 18; Garrett, “The Artist Annie Walke” (pt. 2), 18. ↩︎

See, for example, Tom Cross, The Shining Sands: Artists in Newlyn and St Ives, 1880–1930 (Tiverton, Devon: Westcountry; Cambridge: Lutterworth, 1994); Caroline Fox and Francis Greenacre, Painting in Newlyn, 1880–1930 (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1985); Hardie, Artists in Newlyn and West Cornwall; David Tovey, Creating a Splash: The St Ives Society of Artists; The First 25 years (1927–1952) (Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire: Wilson, 2004); David Tovey, St Ives (1860–1930): The Artists and the Community; A Social History (Tewkesbury: Wilson, 2009); Marion Whybrow and David Brown, St. Ives, 1883–1993: Portrait of an Art Colony (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1994). ↩︎

Philip C. Hills, A Cornish Pageant (Camborne, Cornwall: Philip Hills, 1999); Philip C. Hills, Bring Back the Donkeys: A Tribute to Father Bernard Walke and the Artist Annie Walke (Truro, Cornwall: Philip Hills, 1997). ↩︎

Annie Walke, St Christopher, undated; oil on board, 8 🞨 5 cm; Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro, TRURI : 1994.24. This painting was not examined in person by the authors. ↩︎

Annie Walke, St Clare, undated, oil on canvas, 151 🞨 90.5 cm; former School of St Clare, Penzance. ↩︎

Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 7. ↩︎

C. Roberson and Co. Ltd., 99 Long Acre, London. ↩︎

British Canvas, Stretcher and Panel Suppliers’ Marks 8 (2017), s.v., “Charles Roberson & Co.,” by Jacob Simon, https://www.npg.org.uk/assets/files/pdf/research/artists_materials_8_Roberson.pdf; and Jacob Simon, “British Art Suppliers, 1650–1950” (2018), https://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/directory-of-suppliers/. ↩︎

Sally Woodcock and Judith Churchman, Index of Account Holders in the Roberson Archive, 1820–1939 (Cambridge: Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge, 1997). ↩︎

Jacob Simon, “British Art Suppliers, 1650–1950.” For more on Lanham’s, see Tovey, St Ives (1860–1930), 283–87, 320–24. Sometime between 1917 and 1919, the name of the gallery was momentarily changed to St Ives Art Gallery; Tovey, St Ives (1860–1930), 324. ↩︎

Woodcock and Churchman, Index of Account Holders in the Roberson Archive. ↩︎

Cross, The Shining Sands, 153; Simon, “British Art Suppliers, 1650–1950”; Cornwall Artist Index, s.v. “James Lanham & Co” (n.d.). ↩︎

Walke, Twenty Years at St. Hilary, 166. ↩︎

Studio 8, no. 42 (September 1896): 242–44; also quoted in Cross, The Shining Sands, 153. ↩︎

Tovey, St Ives (1860–1930), 320. ↩︎

Tovey, St Ives (1860–1930) 325. ↩︎

Tovey, St Ives (1860–1930), 324. For more on Porthmeor Gallery, see Tovey, St Ives (1860–1930), 151–52. ↩︎

Hardie, Artists in Newlyn and West Cornwall, 290. ↩︎

“St. Ives Artists Autumn Exhibition,” Cornishman, 17 September 1936: 2. ↩︎

For cold sizing the glue layer used to seal the canvas is applied as a cold gelatinous solution, as opposed to a warm liquid. As a result, the size layer sits between the priming and the canvas, rather than penetrating the canvas fibres. This can result in delamination between the support and the ground in humid conditions. Certain colourmen, such as Roberson and Co., had a practice of preparing canvases with a cold size; see Gerry Hedley, “The Practicalities of the Interaction of Moisture with Oil Paintings on Canvas,” in Measured Opinions (London: United Kingdom Institute of Conservators, 1993), 115. The authors suspected the presence of a cold size due to the widespread flaking between the ground and the support, and because under the microscope the size appears to sit on top of the canvas fibres. ↩︎

The layer structure of the priming – double ground of lead white and chalk, with more lead white in the upper layers – was the standard structure for British commercially primed canvases of this period; see Stephen Hackney, On Canvas: Preserving the Structure of Paintings (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2020), 49. ↩︎

This analysis was conducted on cross-section samples at King’s College, London. All cross-section samples were also examined and photographed with Leica DM 4000 M LED microscope with Leica DFC450C digital camera. ↩︎

Hardboard is a type of high-density fiberboard made by compressing wood fibres. ↩︎

Infrared photograph on Sorrowful Women was carried out with an OSIRIS InGaAs infrared camera, sensitivity 0.9–1.7 µm, while all other infrared reflectography was done in situ with a modified Canon EOS 660D DSLR camera, with an 18-megapixel CMOS sensor and a spectral range of 400–900 nm. ↩︎

Sally Taor, “The Painting Materials and Techniques of William Orpen RA 1878–1931” (PhD diss., The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2006). ↩︎

Non-destructive X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy was carried out with a Bruker Tracer III-SD handheld spectrometer with a 10mm^2^ x-Flash Detector and a Rh target X-ray tube (with S1PXRF software) at The Courtauld Institute of Art; and SEM-EDX at King’s College, London. ↩︎

Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 15 and fig. 21. ↩︎

Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 9–10. ↩︎

Garrett, “The Artist Annie Walke” (pt. 1), 18. ↩︎

Hills, A Cornish Pageant, 16, 42. ↩︎

Hills, A Cornish Pageant, 11. ↩︎

Walke, Twenty Years at St. Hilary, 33. ↩︎

Hills, Bring Back the Donkeys, unnumbered. ↩︎

A Selection of Poems by the Artist Annie Walke. ↩︎

Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 16. ↩︎

“The International Society,” Westminster Gazette, 3–4; “The International,” The Times, 11. ↩︎

An undated archived photograph at the school shows St Clare and Virgin and Child hanging in the old chapel, which opened in June 1918. Virgin and Child is currently hanging in St Hilary Church, where it was likely moved sometime in the 1960s, when the school closed. ↩︎

“Art Exhibitions,” The Times, 31 October 1924: 15. ↩︎

“Outstanding St. Ives Exhibition. Works By Five R.A.’s,” Cornishman, 5 March 1936: 10. ↩︎

“Art Exhibitions,” The Times, 31 October 1924: 15. ↩︎

“600 Women Painters. Racing Greyhounds in an Up-to- Date Exhibition,” Daily Mirror (London), 10 February 1928: 2. ↩︎

“Art Exhibitions,” The Times, 13 February 1928: 17. ↩︎

“Art Exhibitions,” The Times, 31 October 1924: 15. ↩︎

“St Ives Society of Artists Spring Exhibition,” St Ives Times, 3 March 1936; “Outstanding St. Ives Exhibition. Works By Five R.A.’s.” ↩︎

Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 17. ↩︎

Walke, A Boy Returns. ↩︎

Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 16–17. ↩︎

A Selection of Poems by the Artist Annie Walke. ↩︎

Walke, Twenty Years at St Hilary, 54. ↩︎

“The International,” The Times, 11 May 1915: 11. ↩︎

“St Hilary, St Hilary,” in Cornwall Historic Churches Trust Website. ↩︎

Walke, Twenty Years at St Hilary, 106. ↩︎

Melissa Hardie, ed., 100 Years in Newlyn: Diary of a Gallery (Penzance: Patten in association with Newlyn Art Gallery, 1995), 55. ↩︎

Laura Knight, 10 am 2 Queens Road (Drawing of Annie Walke), undated, ink on paper, Tate Archives, London, 895.4; and Knight, Good Works (Drawing of Bernard Walke), undated, ink on paper, Tate Archives, 859.5. Knight’s first impression is also recorded in the painter’s autobiography: Laura Knight, Oil Paint and Grease Paint: Autobiography of Laura Knight (London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson, 1936), 208–9. For more on the Walkes’ personalities, see Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 4–6. ↩︎

Walke, Twenty Years at St Hilary, 38; Hills, A Cornish Pageant, 33. ↩︎

Further information on the plays can be found in Walke, Twenty Years at St Hilary; and Allchin, Bernard Walke, 19. ↩︎

David Matless, “A Geography of Ghosts: The Spectral Landscapes of Mary Butts,” Cultural Geographies 15, no. 3 (July 2008): 347. ↩︎

“St. Ives Artists Autumn Exhibition,” Cornishman, 17 September 1936: 2. ↩︎

The Game (Ditchling, Sussex) 2, no. 2 (9 May 1918). ↩︎

In “Talented Artist of the St Austell District,” Cornish Guardian (Truro), 29 August 1957: 8; the work is recorded with the title Angel of the Ascension, “in which a tall figure is watched by an array of people with tense, upturned faces; a finely imagined and capably rendered work.” In a letter negotiating a sale to the Royal Cornwall Museum, dated 27 November 1992, the work is recorded as Angel Appearing to the Shepherds (RCM.TRURI: 1996.23). The artwork was ultimately sold in a David Lay auction, 10 June 1993, as Preaching from the Hill, along with a number of other artworks by Walke. The painting is currently in the collection of the Royal Cornwall Museum. ↩︎

Pellini and Vesaluoma, “Threads Coming Together,” 15–17. ↩︎

Rachel Monie, “God, Beauty and Imagination Assignment,” unpublished essay, 2018. ↩︎

“Chapel for Private Devotion. Dedication at Truro Cathedral,” Western Morning News (Plymouth), 29 December 1925: 8. ↩︎

“104 Paintings in Exhibition at Wadebridge,” Cornish Guardian (Truro), 29 August 1957: 8. ↩︎

“Works by Cornish Artists. Exhibition at Bath Art Gallery,” Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 12 June 1937: 10. ↩︎

“St. Austell will soon have an Arts Centre. Society acquisition made known at exhibition by newly-formed group,” Cornish Guardian, 13 September 1956: 8. ↩︎

“St. Ives Artists Autumn Exhibition,” Cornishman, 17 September 1936, 2. ↩︎

Despite being applied by the artist, the varnish in Sorrowful Women was removed during the ongoing conservation treatment due to the blanching and discoloration of the varnish, as well as due to decisions made about the structural treatment of the painting. The painting will be re-varnished to restore the intended saturation. ↩︎

Walke is also referred to as “Walke, Mrs. Ann Fearon,” in The Year’s Art, 1913, 562; in The Year’s Art, 1916 . . . , ed. Albert C. R. Carter (London: Hutchinson, 1916), 611; and The Year’s Art, 1922 . . . , ed. Carter (London: Hutchinson, 1922), 508. ↩︎

Exceptions are the privately owned paintings Untitled (Toilers) and London Child II, both signed “A. Fearon Walke,“ which we speculate to signify that these were painted soon after the couple was married. ↩︎

Walke, Twenty Years at St. Hilary, 12. ↩︎

“Art Exhibitions,” The Times, 6 October 1924: 17. ↩︎

“Flower Paintings,” Westminster Gazette, 12 March 1923: 12. ↩︎

“Art Exhibitions,” The Times, 6 October 1924: 17. ↩︎

“Outstanding St. Ives Exhibition. Works By Five R.A.’s”; “Flower Paintings,” 12; “St Ives Artists’ Spring Show,” Western Morning News, 9 April 1937: 4; “St. Austell will soon have an Arts Centre.” ↩︎

S. Kennedy North, “The Art World Modern. Modern paintings equal to past masters. Mrs Fearon Walke: brilliance that is unrecognised,“ Pall Mall Gazette (London), 16 March 1923: 10. ↩︎

S. Kennedy North, “The Art World Modern,” 10. ↩︎

“The Vote Women at home and abroad. Women Artists,” The Vote (London) 27 April 1923: 3. ↩︎

Royal Cornwall Museum and Penlee House Gallery. ↩︎

We have found mention of around thirty different titles, excluding the ones discussed in the present article, that may be in private collections or lost. Some of these we have identified in auction catalogues; others, for which we have not found images, might be duplicates (i.e., a single artwork referred to by different titles, such as Group Portrait with Guardian Angels and Men and Guardian Angels). ↩︎