“Spiritual Abstraction”: The Art and Work of Betty Blayton

Meredith Shuba Watson, Valerie Cassel Oliver, and Carol Woods Sawyer

" “Spiritual Abstraction”1: The Art and Work of Betty Blayton”

Introduction

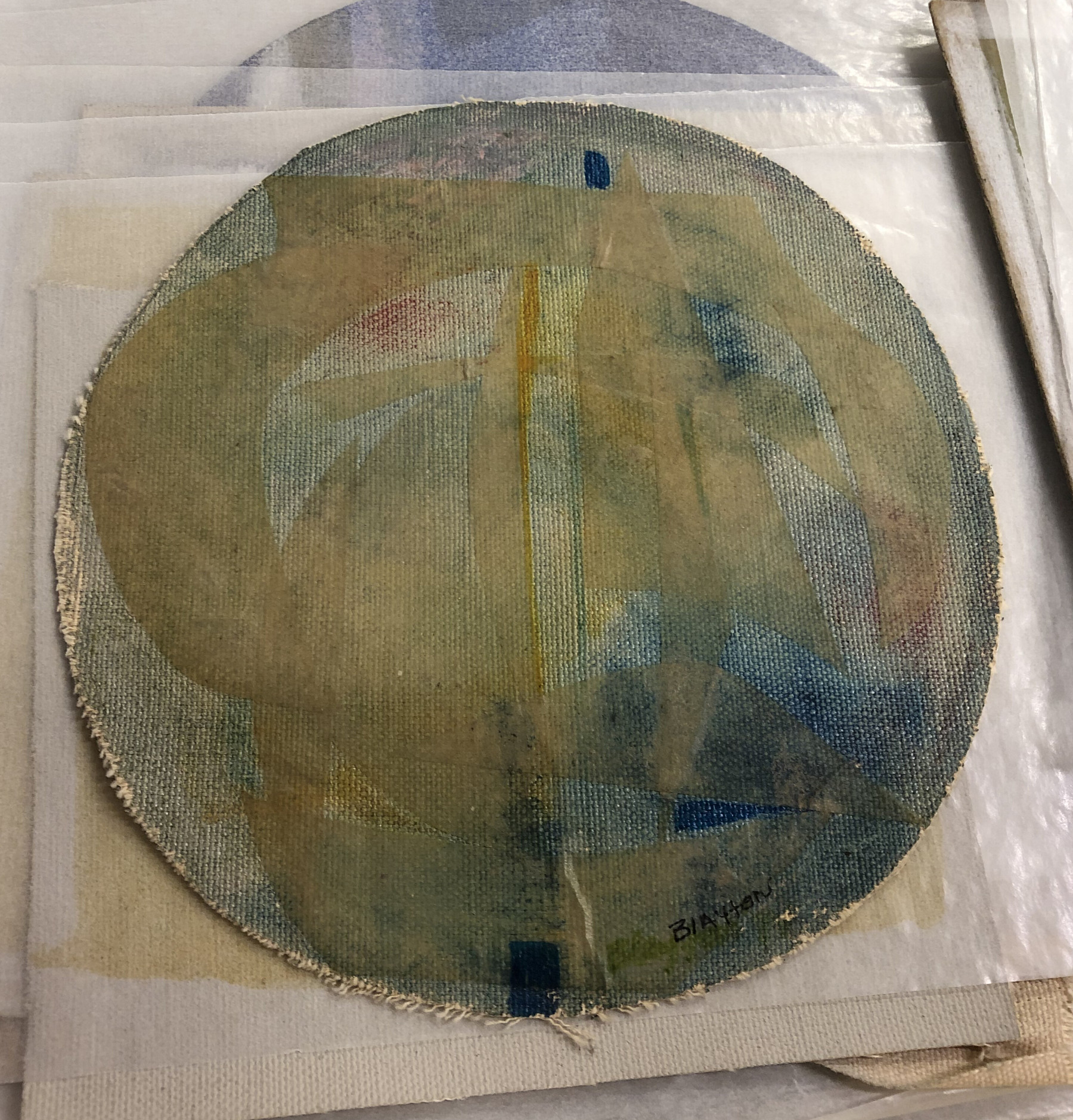

Renewed interest in underrepresented artists from previous decades has brought new found attention to Betty Blayton. As an African American woman working in abstraction beginning in the late 1960s, Blayton was both a pioneer in the field and an advocate for new generations of artists. In 2018, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, VA acquired Betty Blayton’s painting Consume #2 (Fig. 1) a 1969 round abstract oil and paper on canvas. The painting had recently been featured in “Magnetic Fields; Expanding American Abstraction 1960 to Today,”1 an exhibition which, in part, sought to contribute to the “intense curatorial corrective” seeking to expand the canon of abstract art to be inclusive of African American women.2 This iconic painting, one of Blayton’s earliest and largest abstract tondos, is the subject of an ongoing collaborative study in the conservation and curatorial departments at the VMFA. Interviews with the artist’s family and friends supported and enriched the technical study of the painting. Opportunities for research also included the study of other paintings in the Betty Blayton Estate and the Blayton-Taylor papers at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Technical examination utilized primarily non-destructive imaging and analytical techniques including scanning Macro X-ray Fluorescence (MA-XRF), Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), as well as Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) along with visual and microscopic examination.

In an artist’s statement, Blayton wrote: “The intent of my work is two-fold: The first is personal because the act of creating art works allows me opportunities for meditation and self-reflective thoughts related to life’s mysteries and the meaning of being and becoming. The second is hopefully to provide my viewers with opportunities to also engage in meditation and self-reflective thought. I am deeply interested in metaphysical principles, all aspects of religion, mythology, and the science of the mind.”3 Following her death, a retrospective was held at the Elizabeth Dee Gallery in 2017.4 The New Yorker reviewed the exhibition, writing, “These serene, transporting abstractions reveal the spiritual and introspective side of a life devoted to social injustice.”5 Born into a segregated society, the artist worked toward inclusion through art and education, all the while participating in and contributing to the development of abstract art. In one of the first technical studies of Blayton’s paintings, this project explores the materials and techniques of her self-described “spiritual abstractions.”

Early Life and Education

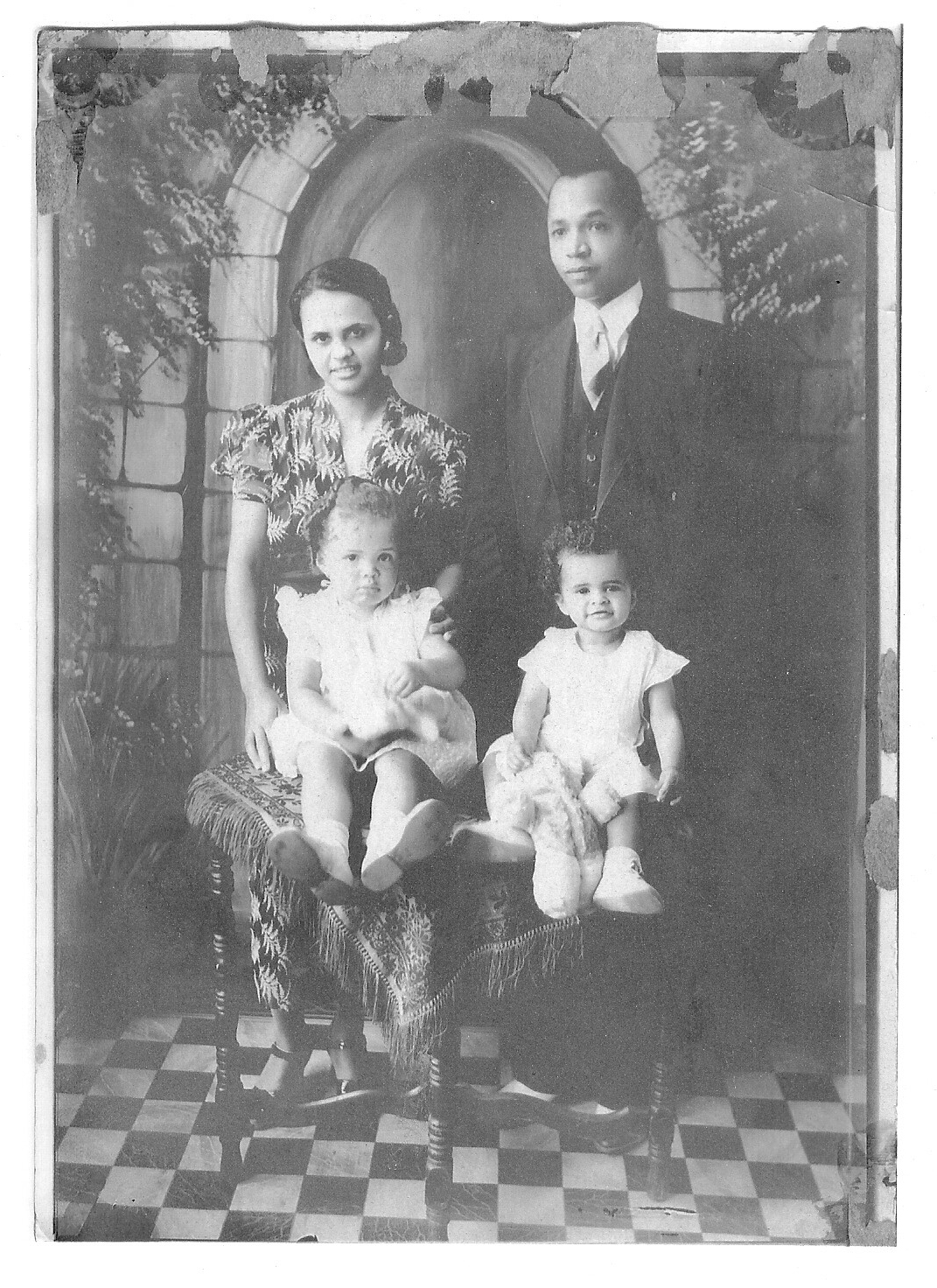

Betty Blayton6 was born in Virginia in 1937 (Fig. 2). Her father, James Blaine Blayton, Sr., attended Howard University in Washington, D.C. as an undergraduate and medical student, before settling in Williamsburg, VA. The first African American doctor in the city, he established a racially inclusive practice and built a 14-bed acute care hospital in Williamsburg. (Until this point African Americans could only be treated in the basement of the city hospital, downstairs next to the boiler).7 Alleyne Houser Blayton, Betty’s mother, was born in Lincolnton, NC in 1910. She began her undergraduate studies at the Hampton Institute (now University) in Newport News and finished a two-year degree in business science at Saint Paul’s college in Lawrenceville, VA. The two married in 1935 and had four children: Barbara (1936), Betty (1937), James, Jr. (“Jimmy,”1943), and Oscar (1945). Following the birth of their children, Alleyne completed her bachelor’s degree and opened a nursery school. She also attended New York University during the summers where she earned her Master’s Degree in counseling and worked for several years as the director of guidance and counseling in the York County Black Public School System. Both parents actively strove to improve living conditions for African Americans in Virginia, and were adamant that their children would grow up knowing empathy and serving their community. Oscar, their youngest son, wrote: “While my father worked quietly, almost under the radar to help African Americans, our mother was constantly “storming the gates.’”8 All four children attended the local segregated Black public school through grade school, and high school at an all-Black private boarding school in North Carolina, the Palmer Memorial Institute (though both boys also studied at boarding schools in New England as well).9

Betty Blayton declared herself an artist from a young age. In an interview in 1997, Blayton said, “I cannot remember ever not thinking I was an artist.”10 A replica of Augusta Savage’s Lift Every Voice and Sing sat on the piano in her parent’s home, and she recalled identifying with it as a child. She spent her youngest years in the art room of the school where her mother taught, and when she was older she had an art teacher in elementary school who allowed her to spend time working in the art room instead of attending class. By the sixth grade she was painting in oils. As there were no accredited college art degrees available to her as an African American in segregated Virginia, she attended Syracuse University, paid for by the Commonwealth under the “separate but equal” law.

Syracuse had one of the most prestigious art programs in the country, and Blayton received funding for all four years. In 1959, she earned her BFA in painting and illustration, completing her degree with honors. Following graduation she spent a brief time in Washington, DC where she met and became friends with members of the Washington Color School, notably Sam Gilliam, among others. She later moved to St. Thomas to teach, and here her painting shifted from more figurative work to landscapes that pulsated with a more abstract quality. By the time she returned to New York in 1961, her paintings were loosely figurative, primarily city street scenes of Harlem with varying degrees of dissolution and teetering upon the abstract (Fig. 3). In New York, Blayton worked with and learned from Arnold Prince, Bob Blackburn, and Nizuma among others. Blayton continued course work in both art and education at the Art Students League and the Brooklyn Museum School before stepping into her very active role in the advancement of youth in art and education, particularly the community living in Harlem.

Educator and Activist

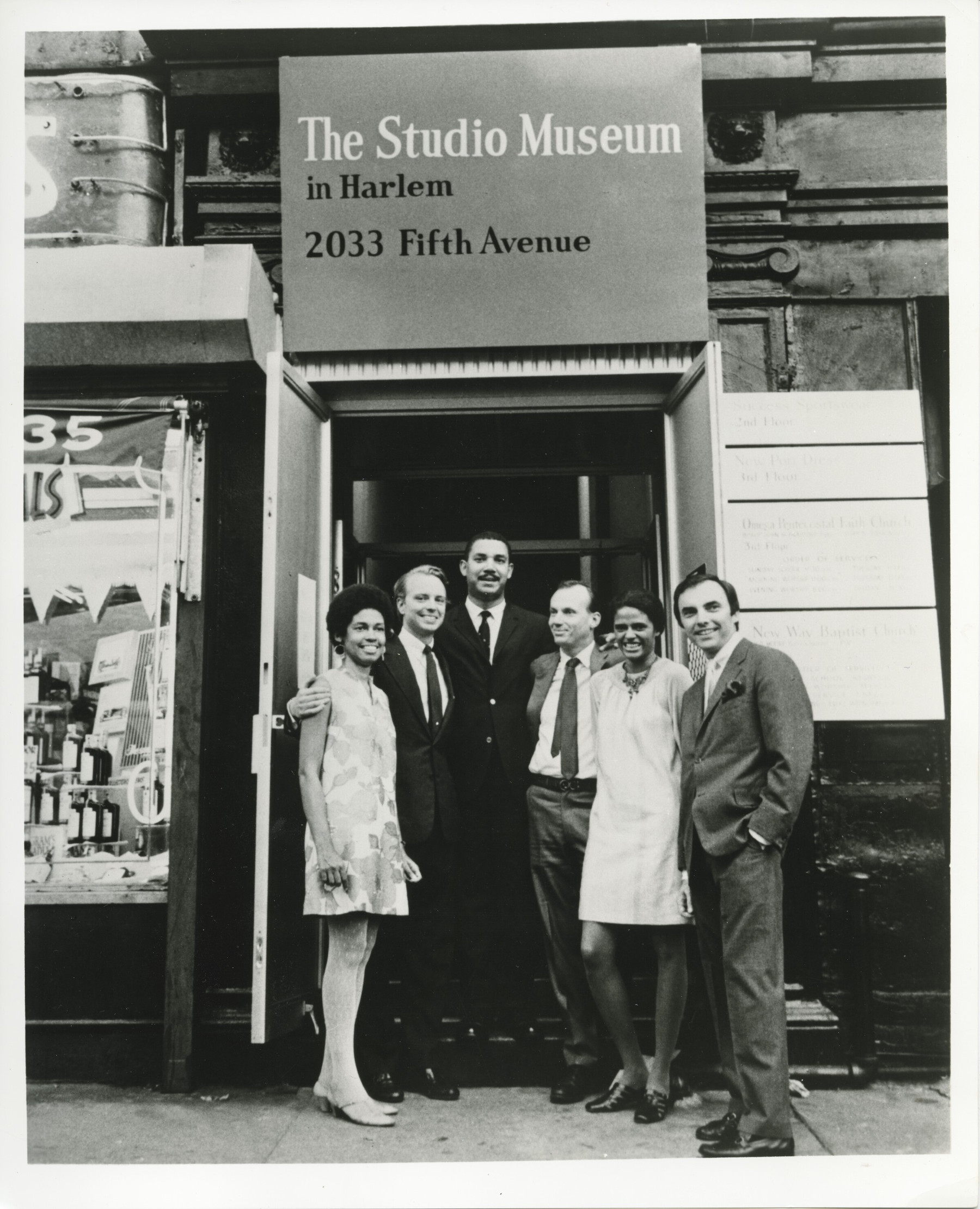

Blayton was a founding member of the Studio Museum in Harlem (Fig. 4) and a board member from 1965 until 1977. Thelma Golden, director and curator of the Studio Museum, explained that in founding the Studio Museum, Betty had a clear vision for an institution that “was deeply committed to creating access for young people, frequently discouraged from entering museums and visual art institutions in New York City.”11 Her brother Oscar recalled that while working with children in Harlem, Blayton used to send her students to see exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Before they arrived, Blayton would have to call her colleague at MoMA, Elizabeth (Liz) Shaw, to arrange for the security guards to let the students into the museum – assuring them these groups of children were legitimately interested in art and not there to cause trouble.12 Blayton stood firmly in her beliefs. For example, she resigned from the board of the Studio Museum in 1977 over the proposed relocation to 104^th^ street, which was recommended in an effort to attract middle class white visitors.13 While the move was eventually reconsidered, and the building instead relocated to 125^th^ street, her protest was based on her founding principle that the museum was to serve her neighborhood and community in Harlem. Similarly, in 1971 she aligned herself with the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, withdrawing her work from the Whitney Museum’s “Contemporary Black Artists in America” in solidarity over the lack of African American curators.14

She was similarly passionate about the importance of the arts in education and its critical contribution to childhood development. Speaking on the topic, Blayton said, “It is the arts that make you unique, different, give you your individuality, and are going to make the difference between how we moved forward as a race of people, a nation, a world. We need opportunities to explore our subconscious. Without the chance to do that, concrete creativity would never be realized.”15 For four years, Blayton worked with the teenagers of HARYOU (Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited)16 before partnering with MoMA and the Harlem School of the Arts to found the Children’s Art Carnival, an arts education program for inner city youth. She was the executive director of the program from 1969 to 1998 and continued to be involved with the program until her death in 2016. A 1971 documentary film titled FIVE17 featured an interview with Blayton in which she described the Art Carnival, saying, “The basic philosophy of the Children’s Art Carnival is that we are trying to develop creative human beings. Young people who are capable of the kinds of thought that goes into creating, say a painting, a piece of sculpture, a collage, is ultimately the same kind of thinking that goes into producing a creative human being; flexibility, imagination, the ability to rearrange and change. Realizing what something is and at the same time being able to see it for what it could possibly be. And we feel this is what is missing in so many people’s lives, not just the kids in Harlem.”18 The Children’s Art Carnival continues to inspire and teach children in Harlem to this day, teaching 5,000 to 10,000 youth per year. Artists such as Michael Kelly Williams, Emily Berger, and Jean-Michel Basquiat were students there.19

Artist

While devoting herself so fully to art education, Blayton continued to be an extremely prolific artist in her own right (Fig. 5). Her roommate and co-worker at the Children’s Art Carnival, Martha Norris Gilbert, recalled that she would work all day and then come home to their apartment and paint all night. “She would start a painting and work until three o’clock in the morning.”20 Blayton was an accomplished painter, sculptor, and printmaker, and her creative and artistic contributions did receive some recognition during her lifetime, but these accolades were primarily recognizing her work as an educator and administrator. She received the “New York State Governor’s Art Award” in 1989, the Women’s Caucus for the Arts “Lifetime Achievement Award” in 2005, and a Joan Mitchell Foundation CALL grant in 2014.21 She exhibited at MoMA, the Studio Museum, The Whitney, Howard University, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and the Rhode Island School of Design. In the fall of 1973 her work was featured on the cover of Contact magazine, “Black Women in the World of Work.”22 Solo exhibitions included the Adair Gallery GA, The Capricorn Gallery NY, Spelman College GA, and the Fisk Gallery TN. However, her first major solo exhibition was not until after her death.

Through her work Blayton developed close friendships with important artists in New York, and stated that it was this community of artists that kept her in the city throughout her lifetime. Among many others, Blayton was close to Romare Bearden (whom she called Remy), Faith Ringgold, Norman Lewis, and Arnold Prince. In an interview toward the end of her life, Blayton said her “family” of artists included “just about every African-American artist in New York City over the age of 40.”23 A recent exhibition,24 curated by Susan Stedman at the Art Students League in New York, revisited many of the artists with whom Betty associated. Like Betty, artists like Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis were teachers during their careers, and “In the world of art education, they were respected, while in the domain of commercial art galleries they were marginal figures at best.” 25 However, many of these artists were also pioneers in abstraction, operating in a racially exclusionary art world.

Like her peers working in abstraction, Blayton sought a freedom to explore the various sources of inspiration including the spiritual realm. Her works were free expressions of the ethereal, dimensional landscapes that she captured in physical form. For her, painting was a meditative process. Blayton acknowledged that Kandinsky had a significant influence in her work, and she discussed his use of color with Norman Lewis when they taught together at HARYOU.26 Early in her career she felt a connection and inspiration in El Greco. Like these artists, spirituality, color and form drove her work. Yet while her early career also saw her in conversation with other abstractionists such as Howardena Pindell, Sam Gilliam, and Frank Bowling, Blayton never received the commercial success of these artists during her lifetime.

In an article following Blayton’s death, Lowery Stokes Sims, curator and art historian remarked, “It is a truism that Betty was a strong artist for whom, like many of her peers – especially women – her art took a backseat to her decision to work on behalf of the larger art community.”27 Her brother Oscar went one step further and commented that Betty had a full time career in arts education but she always had a need to create, so she never stopped producing art. The part of her career that suffered, he lamented, was that Betty did not have time to actively promote her work, and as a result most of what she made remained in her possession at the time of her death in 2016.28

Consume #2, 1969

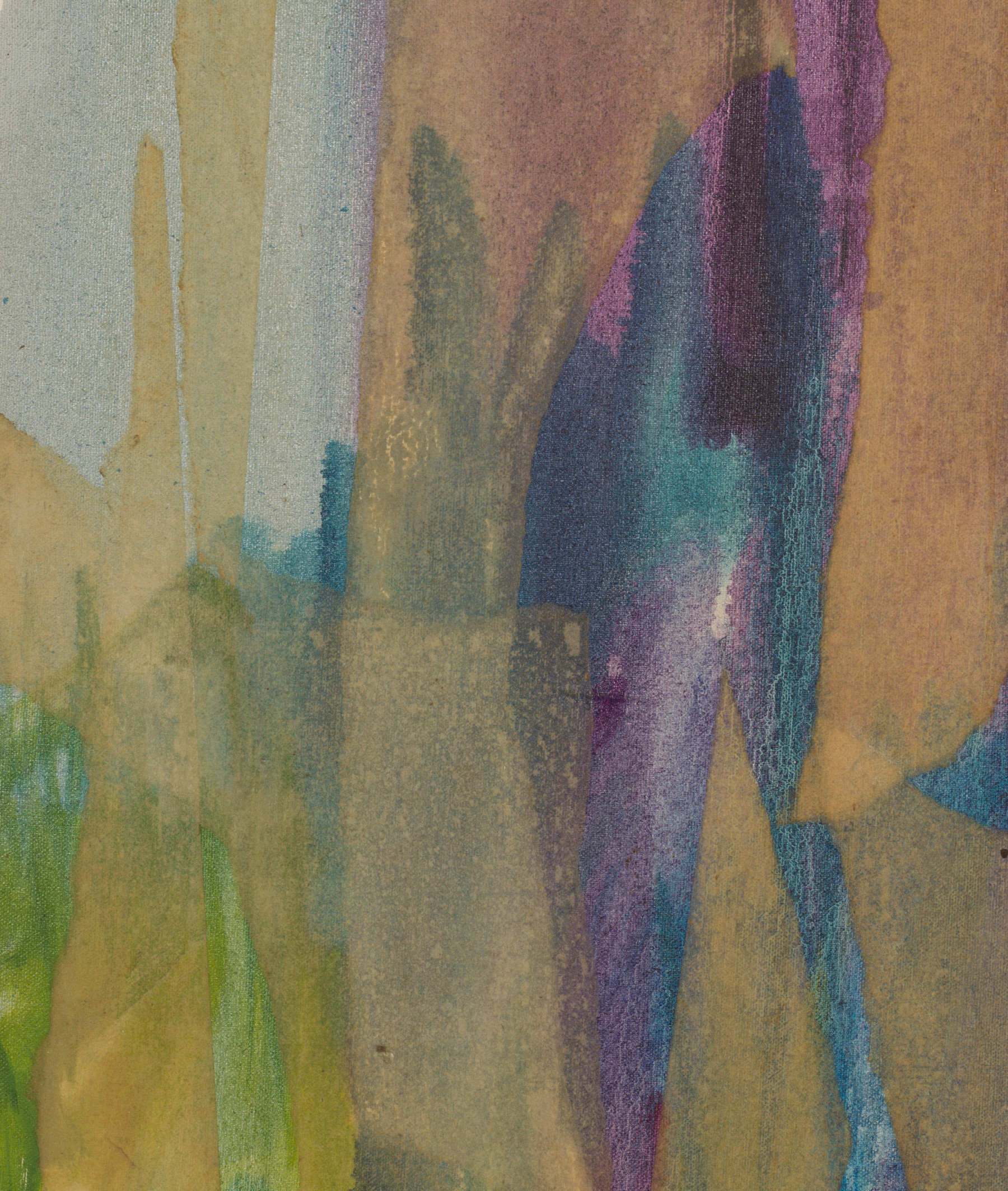

Consume #2 was one such work, which remained in Blayton’s cigarette smoke filled studio and then her estate until it entered the VMFA permanent collection in 2018. The round colorful abstraction, and the focus of this study, combines brushwork, thin washes, and drips with paper collage elements. Fifty-nine inches in diameter, it has passages of transparent blues, pale purples, pinks, and greens with more highly pigmented deep blues and purples on a white background. There are torn and cut paper elements, once pale and somewhat transparent, that are now discolored and unevenly opaque. The adhesive used to apply the paper acts also as a partial coating, creating variations in surface gloss overall. It is signed in blue in the lower right, “Blayton 69” (Fig. 6).

Consume #2 is one of the earliest abstract tondos examined to date, and its round format and collage construction were characteristic of her technique for the remainder of her painting career. From the late 1960s, her use of circles and layering continued to dominate the visual language of her paintings. Chloe Wyma, contextualizing Blayton’s work within the historic use of tondos wrote: “From fifteenth century Madonnas to Robert and Sonia Delaunay’s spiritualized formalism, the tondo format has historically conveyed a cosmic holism, intimating a transcendent space unhampered by corners of limits.”29 Blayton explained the significance of the circular format, saying, “Using circles, as a form, basic form, for painting, it is very symbolic to me. The circle is never ended, and I believe that life is often this way in terms of stages of ones being, so to speak, starting from babyhood and moving on….And this is how a person grows. And it’s a constant hitting points over and over again as you would in a circle. You know you go back and you repeat, but every time you spring out a little further and you come back and you spring out again.”30

The painting is executed on a finely woven, plain weave cotton canvas with a double warp thread (15 vertical threads x 35 horizontal threads per square cm.). This is consistent with other contemporary examples of her paintings examined in this study, which appear to use the same canvas type with a similar thread count.31 The canvas is mounted on its round strainer with staples along both the edges and the verso. Blayton’s roommate from New York recalled her working from rolls of pre-primed canvas, and then stretching them onto the strainers herself.32 The priming of Consume #2 is bright white, extends to the cut edges on the verso and is composed of chalk in an oil binder.33 It is in plane, despite a wide open window and the lack of cross members supporting the strainer.

The wooden strainer is ¾ inches wide and 1 inch deep. It is a laminate construction of four thinner (approximately ¼ inch) strips adhered together. Again—it is identical to comparable works from this period, though the source of these strainers at that time (which varied greatly in size) is currently unknown. Later in her career (in the 1980s and 1990s) Betty’s brother, Jimmy, also a sculptor, often constructed them for her.34 The strainers Jimmy made were fabricated from plywood, cut in circular forms and supported by metal brackets. The strainer for Consume #2, however, more closely resembles a wooden embroidery hoop in its construction.

Blayton’s artistic process during this time period is well documented in FIVE.35 In the documentary, she describes her process, explaining that each painting begins with a careful plan and sketch. Blayton received a formal art education, and her methodical careful planning of even her most organic appearing works reflect her cognitive approach. Fortunately, many of these concept sketches and prototypes are preserved in her estate and were available for study (Fig. 7 and 8). She made both small (approximately 3.5 inch diameter) watercolor sketches as well as slightly larger (7 inch diameter) mock-ups on canvas, where she applied paint and the paper collage elements. The time and effort she devoted to this preliminary work resulted in carefully calculated compositions, and illustrate Blayton’s inventive and exploratory approach. These sketches were tacked onto the wall while she worked, and the design was transferred onto large canvases using chalk outlines.36

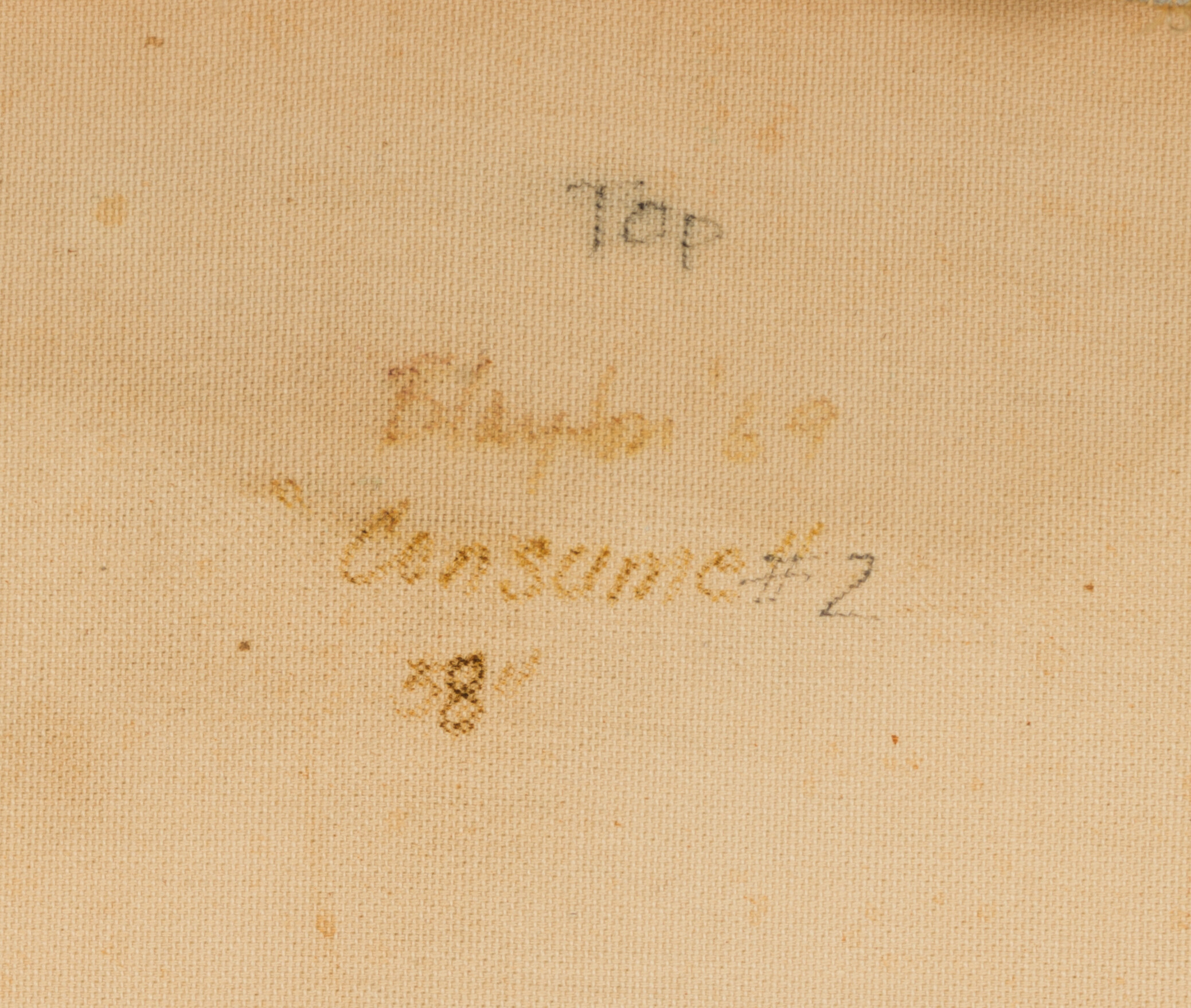

A flat brush was used to apply dilute thin washes of paint. In Consume #2, the pale blue layer was applied first, followed closely by darker colors that were allowed to bleed and seep into the pale washes. Applied wet into wet, drips are visible and there are passages where the colors blend and feather together. Based on the direction of the drip marks and the composition, it is likely Consume #2 was painted in a variety of orientations, contributing to the dynamic sense of motion in the work (Fig. 9). The staining extending around the tacking margins in the upper half of the verso also suggests the painting was executed in the reverse orientation from its current positioning. It was also displayed, at least once, in the opposite orientation from which it is now exhibited and signed. It was included in an exhibition titled 15 Women at the Taylor Art Gallery and Bluford Library at the North Carolina A&T State University, (now the H. Clinton Taylor Galleries and the F.D. Bluford Library), curated by Greensboro artist and Professor Eva Hamlin Miller. Other artists in the exhibition included Alma Thomas and Faith Ringgold. The exhibition was in 1970 (just one year after this painting is dated) and Consume #2 was displayed with its current bottom edge at the top in the exhibition catalogue.37 The effect of the reverse orientation is substantial; the “weight” of the forms would have appeared settled along the bottom. As it is currently displayed, the forms appear to defy gravity, lending an ethereal quality to the work. After the 15 Women exhibition, Blayton added her signature to the painting, and labeled “top” on the verso, confirming her preferred orientation. Omar Blayton, Betty Blayton’s nephew, commented that because her paintings were round, they were frequently hung in the wrong orientation and that it used to “drive Betty crazy, because she was so particular about her compositions.”38 At a later date, she went back and wrote “top” on many of her paintings, along with the date and title. The inscription “#2” on this painting also appears to be an even later addition (Fig. 10).

Paint

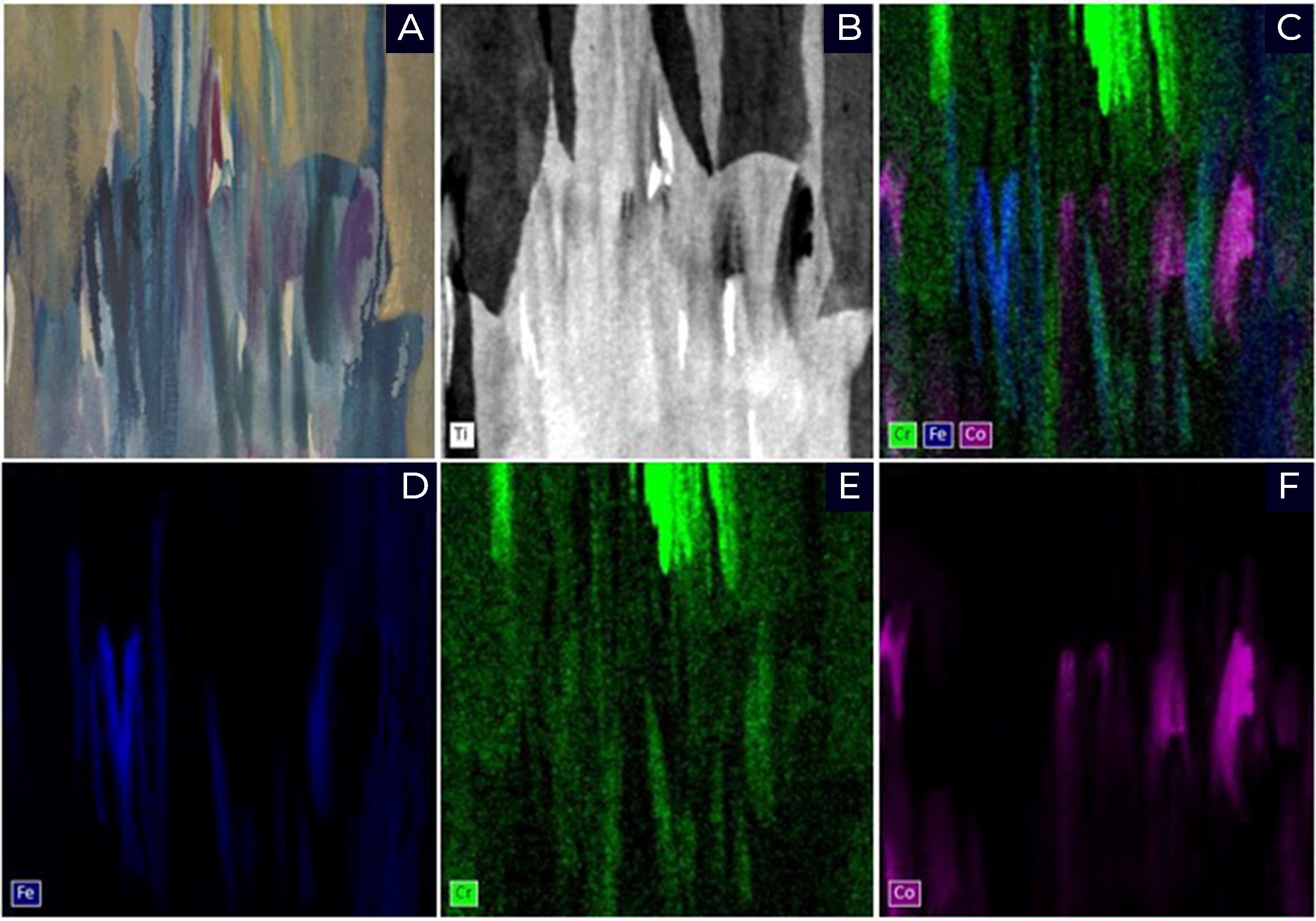

The paint layer is extremely thin and in good condition, with no losses in the painted pictorial layer and only minor abrasions and staining overall. MA-XRF was used to non-destructively identify the elemental composition of the materials, avoiding sampling the well-preserved surface. Primarily composed of blues, purples, and small amounts of green and yellow on a pale off white background, the palette is limited. The bleeding of the colors in this work is also somewhat distinctive from her often more geometric compositions.

A CRONO Macro-XRF scanning system was used for both spot acquisitions as well as element mapping. Elemental analysis of the purple indicated her use of cobalt violet (Cobalt (II) Arsenate), a pigment that has not often been identified in conservation literature in general.39 Cobalt violet (arsenate) is no longer on the market due to its toxicity, and was phased out by manufacturers in the late 1960s, facilitating its use in dating paintings.40 In Consume #2, the vibrant purple passages contain cobalt, arsenic, and zinc (but no magnesium was identified, which might indicate Cobalt Violet Dark).41 She also used Prussian Blue, suggested by strong iron peaks in these highly pigmented dark blue areas. Prussian Blue was further supported by FTIR analysis of a small sample taken from the rear turnover edge, which exhibited bands characteristic of Prussian Blue. Other elements identified included titanium, chromium, cadmium, as well as sulfur, potassium, and calcium - indicating the use of titanium white (Titanium Dioxide), cadmium yellow (Cadmium Sulfide), and a chrome based green (Fig. 11). Blayton’s palettes, like her compositions, were purposeful and fundamental in building the transformative portals she created. The application of the thin washes of emotive color were all part of the meditative practice of her work, and her choice of pigments was extremely important throughout her career.

Paper

Once the initial paint layer was dry, Blayton would tear or use scissors to cut paper into desired shapes and adhered them to the canvas using a brush. In FIVE, Blayton explains, “…the tissues really build the structure of the painting. Actually, the structure starts with the sketch and it’s already pretty much laid out, but the strength of the painting is supported with the tissues.”42

The collaged paper elements were applied in numerous pieces and layers. The paper is thin to medium weight and smooth, composed of a combination of short and medium length fibers.43 It is highly processed, and discrete spots of bare paper suggest that it is cream in color.44 However, the paper elements are almost entirely impregnated with adhesive, which increased its translucency, but also discolored and embrittled the paper. It is highly likely that the paper was paler and more transparent when it was applied, and that the passages of paint, below the paper elements, were more visible.

The layering of paper and paint was a technique she revisited and developed throughout her career. The painting collages of the early 70s suffer the most from discoloration, as the paper in these compositions is exposed, covered only with an acrylic coating that exacerbated the accumulation of grime and the deterioration of the paper. In later works, she began toning the paper, and experimented more with layering paint over the tissue. The darkening of the paper in these later paintings, therefore, is not as visible. Eventually, she also began using a higher quality paper that does not appear to have suffered the same degree of deterioration.

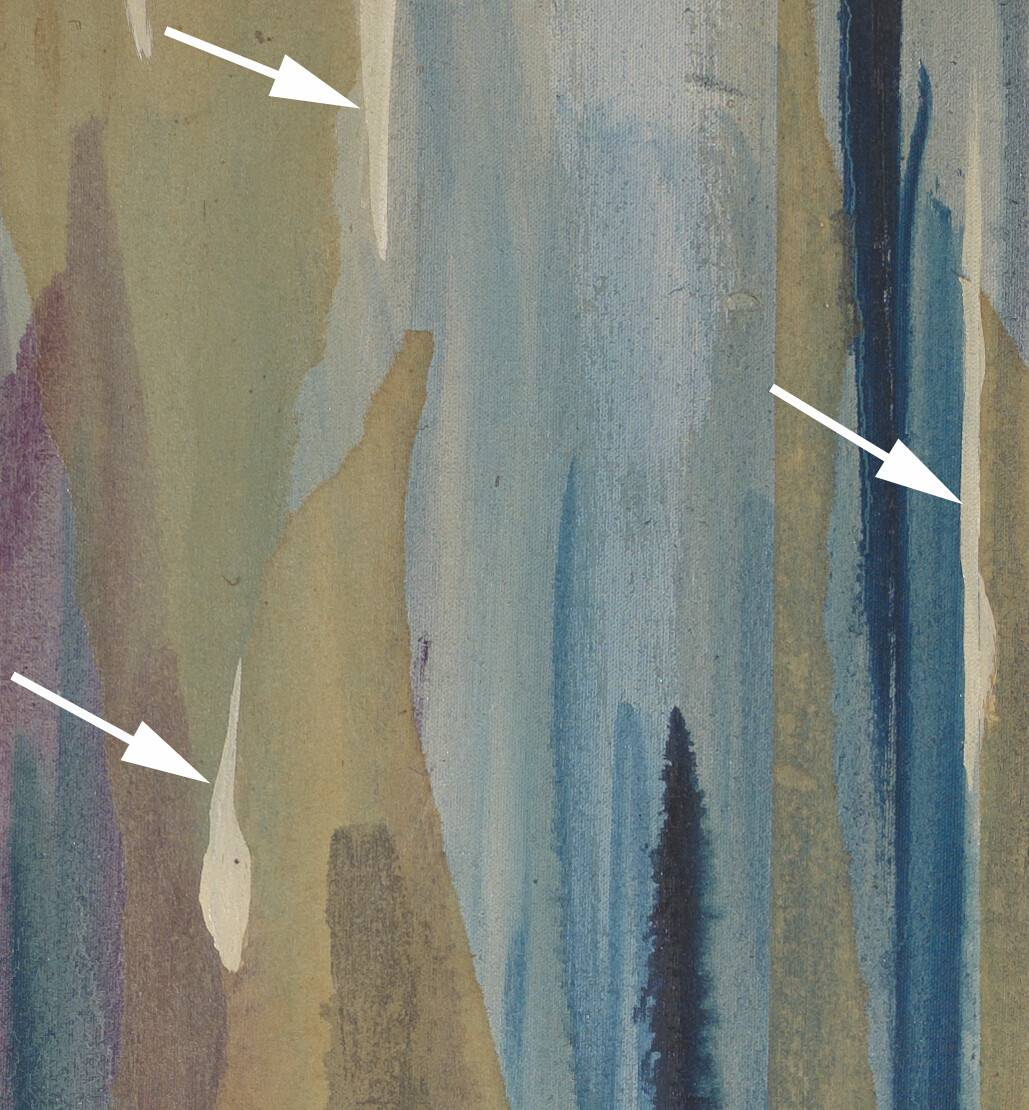

FTIR analysis of a sample of the adhesive taken from behind a lost paper element from Consume #2 identified it as a commercial acrylic adhesive, similar in composition to a Liquitex Acrylic Gel Medium. The adhesive was brushed over the paper elements in multiple directions, saturating the paper and extending beyond the paper onto the paint layers. Some of the paper fibers along the edges were loosened and frayed during the process - swollen from the moisture of the adhesive and pulled by the brush bristles during application (Fig. 12). The wet paper was left to dry completely before returning to the area with a more opaque, heavier bodied paint for contrast and accents. In Consume #2, titanium white paint was used to sharpen and define the outlines. This last applied white layer occasionally extends over other colors and the paper, refining the lines and adding false “negative” space. When viewed from a distance these passages read as gaps or voids between the paper and painted passages. However, upon closer inspection it is evident that they are actually added shapes, purposefully defining and balancing the composition (Fig. 13).

The order in which the pieces were applied, and the variation in the surface coating were most accurately recorded and understood utilizing RTI. The RTI data provided information to carefully monitor the variations in the opacity, thickness and adhesion of the paper elements. The imaging data documented not only the subtle texture variations and thicknesses of the paper, but also areas where there may be separation of the paper from the canvas. It also made it possible to understand the order in which the paper layers and paint were applied (Fig. 14). The strength of the adhesion of the paper to the canvas varies. It is separating and lifting along some of the edges and over canvas slubs. Losses have occurred as well, including a large loss in the upper right (from which the adhesive sample was taken).

RTI also provided a map of the acrylic coating, brushed liberally over the paper elements and extending well beyond onto the painted passages. The glossy coating is not universally applied. A similar coating was also noted on her paintings that did not have any applied paper, indicating this uneven gloss was an aesthetic effect, not just a practical result of adhering paper, and was therefore acting as both a varnish and a sealant. Unfortunately, the coating has also darkened and discolored, imbibing grime and diminishing contrast and dulling the palette.

Frame

Like many of her other works, the tondo is framed in a simple strip frame, applied by the artist. Composed of aluminum (trace elements of silver were also identified with MA-XRF), the stripping is comparable to commercially available counter-top edging found in kitchens (Fig. 15). Its front face is ¼” wide, and the side edges are 7/8” deep, with nails spaced regularly, 6” apart. Mrs. Gilbert, Blayton’s roommate, recalled Blayton using a hammer to attach the striping with nails once she completed the paintings, often extremely late at night.45

Conclusion

The painting Consume #2 marked a pivotal time in the development of Blayton’s work - from the 1970s onward her paintings and painting collages were decidedly abstract, contributing to the conversation of contemporary art at that time. The technical study of this work, and a new understanding of her process, reveals meticulously planned and painstakingly arranged compositions that at the same time provide a space for meditation and thought. The refuge she created in her contemplative self-reflective paintings counterbalanced her outward engagement with the art world and its strained relationship with her community. Commercial art in New York was as segregated as the school system in Virginia where she grew up. Like so many Black artists of her generation working in abstraction, Blayton would have to wait for many decades to be recognized and valued for her work. Robin Holder, a friend and visual artist, wrote “A difficult thing that has to do with elitism in the art world is that community art is often regarded as “lesser than” the arts. Blayton was the founder and director of a community-based African American organization, and because of that I hope she is not sidelined in importance, [because she was] a genuinely gifted and hardworking abstract painter. Sometimes I wonder whether, if Betty had spent more of her life developing her work, and if there was more of a receptive art world to female African-American artists, she might have been more high profile.”46 Only recently has she gained the attention of a wider audience. A 2021 exhibition at the Mnuchin gallery in New York featured over fifty of her paintings, thematically relating her works over the span of her decades-long career.47 The paintings were examples of the nuanced surfaces, structural integrity, and masterful use of color characterized in the study of Consume #2. On view were the spaces she created for inward examination and beauty, transcending both the real and perceived limitations of an exclusionary and unjust art world.

Methods

Macro XRF Fluorescence (MA-XRF)

Scanning MA-XRF is a non-destructive imaging technique that allows for elemental mapping of an object, most often used for the characterization of inorganic elements which can contribute to the identification of pigments and materials. MA-XRF was carried out using a Bruker CRONO. The measurement head is mounted on a motorized stage with the optimum scanning distance between 5-7mm from the subject. It can scan an area up to 60 x 45 cm. Bruker CRONO software 1.2.4.54 was used for instrument control and data collection. The CRONO has an x-ray tube with Rh-target, 10-50 kV, 5-200 µA, 10W, four software selectable X-ray filters, and three software selectable collimators (0,5, 1, 2 mm). The instrument detector is a 50 mm^2^ Silicon Drift Detector (SDD). Analysis of Consume #2 was conducted vertically on an easel without a filter at 50kV, 100 µA, and a 1 mm collimator setting. Spot analyses were conducted for 40 seconds. Bruker software ESPRIT (Reveal 2.2.1.4280) was used for analysis of the data collected.

Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI)

RTI is a computational photography technique that, using mathematical enhancement and computer algorithms, provides surface information related to an object by extracting information from a series of sequential photographs and lighting to produce a digital file.48 The interactive re-lighting of the painting that is possible using the digital RTI file allows for visualization and documentation of surface phenomenon and nuances difficult to see and capture otherwise. Documentation of Consume #2 used the highlight capture method, in which the painting lay flat in a large space. Both the painting and camera remained stationary while a portable light was sequentially maneuvered around the painting at different angles, creating a hemispherical data set of photographs.49 RTI Viewer software 1.1.0 was used to view the file.

Photography

Digital Photography was carried out using a Hasselblad H6D Medium Format DSLR Camera with Broncolor Siros 800s RFS21 strobe lights.

Microscopy

A Zeiss Axioskop microscope was used for examination. Samples were mounted in water on 1.0 mm glass microscope slides under 0.16-0.19 mm colorless borosilicate cover glass. Calibrated photomicrographs were produced using a 10-megapixel Amscope Microscope Digital Camera MU1000 placed within a C-mount and driven with Amscope software (version x64, 3.7.7303).

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (bench ATR)

FTIR is an analytical technique using infrared light to characterize the chemical properties of a sample and help identify organic, polymeric and some inorganic materials. Analysis of samples were carried out with the Thermo Nicolet iS50 FT-IR with diamond ATR bench and DLaTGS detector, set to collect and average 32 scans at a resolution of 4.00cm^-1^ spectral resolution. Interpretation of the spectra was aided by searching in the OMNIC software (Thermo Scientific, version 9.8.372) against a variety of spectral libraries including those purchased with the instrument as well as the IRUG libraries of common conservation and artists’ materials.50

Acknowledgments

This research was based within The Susan and David Goode Center for Advanced Study in Art Conservation at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA. The authors would like to thank the Blayton family—Oscar, Barbara, and Omar—for their generosity of time, resources, introductions and kindness, without which this project would not have been possible. We extend many thanks to the Art Handling, Curatorial, and Conservation departments at the VMFA and are particularly indebted to Michael Taylor, Chief Curator and Deputy Director for Art and Education, Sam Sheesley, Senior Conservator and Head of Paper Conservation, and Ainslie Harrison, Conservator and Head of Sculpture and Decorative Arts, for their assistance, expertise, and enthusiasm. Thank you also to Travis Fullerton, Chief Collection Photographer and Manager of Imaging Resources, and Sydney Collins, former Conservation Photographer, for support in photography and RTI, and to Nick Barbi of nSynergies, Inc. for assistance in the CRONO analysis and interpretation of the data. Finally the authors are deeply grateful to Stephen Bonadies, Senior Deputy Director of Conservation and Collections, for securing financial support for this research and to the Institute of Museum and Library Services for funding the project.

Authors

[Meredith Shuba Watson]{.ul} is an Assistant Conservator of Paintings and the Paul Mellon Collections at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA. Previously, she spent two years as an Advanced IMLS Fellow in Paintings Conservation at the VMFA, worked in private practice, and was an Assistant Conservator of Paintings at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC and ARTEX Fine Art Services in Landover, MD. She trained at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, receiving a Post Graduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings in 2009. During her training, she was an intern at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, DC, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Ashmolean in Oxford, UK. She also presented and published a paper in the 2010 Smithsonian Conference “New Insights into the Cleaning of Paintings” in collaboration with the Van Gogh Museum and the Instituut Collectie Nederland. Before attending the Courtauld, she earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Art History from Davidson College in North Carolina. Email: meredith.watson@vmfa.museum

[Valerie Cassel Oliver]{.ul} is the Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Prior to this position, she spent sixteen years at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Texas, where she was senior curator. She was director of the Visiting Artist Program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a program specialist at the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2000, she was one of six curators selected to organize the Biennial for the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Cassel Oliver has organized numerous exhibitions including the acclaimed Double Consciousness: Black Conceptual Art Since 1970 (2005); Cinema Remixed and Reloaded: Black Women Artists and the Moving Image with Dr. Andrea Barnwell Brownlee (2009); Hand + Made: The Performative Impulse in Art and Craft (2010); and Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art, (2012), which toured through 2015. Cassel Oliver has also mounted numerous solo exhibitions including a major retrospective on Benjamin Patterson, Born in the State of Flux/us, as well as the surveys, Donald Moffett: The Extravagant Vein (2011); Jennie C. Jones: Compilation (2015); Angel Otero: Everything and Nothing (2016); Annabeth Rosen: Fired, Broken, Gathered, Heaped (2017); and Howardena Pindell: What Remains to be Seen (2018). Her current exhibition, “The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse,” was recently on view at the VMFA and will open at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston, TX before traveling to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, AR and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver, CO. Email: valerie.casseloliver@vmfa.museum

[Carol Woods Sawyer]{.ul} is the Margaret H. and William E. Massey, Sr. Conservator of Paintings and Head of Painting Conservation at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA. Prior to her current position, she was a Sherman Fairchild Fellow in the Painting Conservation Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1980-1984. She earned her Bachelor of Arts Degree in Art History in 1976 from Stanford University in California, and her Master of Fine Arts in Conservation in 1980 from Villa Schifanoia in Florence, Italy, Rosary College Graduate School of Fine Arts. Sawyer’s publications include: “Poussin’s Holy Family on the Steps: New Technical Discoveries, Comparisons, and the Washington Copy” with Marcia Steele, Cleveland Studies in the History of Art (1999); “Discoveries Concerning Poussin’s Techniques Made During the Examination and Treatment of Achilles Among the Daughters of Lycomedes,” Kermes, La Revista del Restauro special issue Nicolas Poussin: Technique, Practice, Conservation, (2014); “A John White Alexander Painting: A Comparison of Imaging Techniques for Resolving a Painting under Another Painting” with Erich Uffelman et.al., JAIC special issue Reflectance Hyperspectral Imaging to Support Documentation and Conservation of 2D Artworks (2019). She also presented, “Discoveries Concerning Poussin’s Techniques Made During the Examination & Treatment of Achilles Among the Daughters of Lycomedes” at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (1995) and “Two of A Kind: Cleveland’s and Washington’s Holy Family on the Steps” at The Cleveland Museum of Art Poussin Symposium (1999). Email: [carol.sawyer@vmfa.museum]{.ul}

References

“Art; Betty Blayton,” Goings on About Town, The New Yorker, accessed 24 May 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/goings-on-about-town/art/betty-blayton

“Betty Blayton” Exhibitions, Elizabeth Dee Gallery. Accessed 24 May 2019. http://www.elizabethdee.com/exhibitions/betty-blayton

Blayton, Betty. Artist statement, 2006. Box 2, Folder 8. Betty Blayton-Taylor papers, 1929-2016, bulk 1970s-2000s. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Corbeil, Marie-Claude, Jean-Pierre Charland, Elizabeth A. Moffatt. “The characterization of cobalt violet pigments,” Studies in Conservation 40 Number 4 (2002), 244. Eminhiser-Harris, Karen “Women of Color Find Their Rightful Place in the History of American Abstraction,” Hyperallergic (August 22, 2017). https://hyperallergic.com/396111/women-of-color-find-their-rightful-place-in-te-history-of-american-abstraction/

FIVE Artists. Directed and produced by Vicki Kodama, 1971. The National Archives and Records Administration. https://archive.org/details/gov.archives.arc.50813

Hatch, James V. and Judy Blume eds. “Interview of Betty Blayton-Taylor by Halima Taha, November 9, 1997” Artist and Influence Vol.17:1-199 New York, NY: Hatch-Billops Collection Inc. (1998).

Hughes-Hallet, Molly, Christina Young and Paul Messier “A Review of RTI and an Investigation into the Applicability of Micro-RTI as a Tool for the Documentation and Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Paintings.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation VOL.60 No.1 (2021): 18-31.

Kambon, Mariamma “Journey of a soul; the life and work of Betty Blayton Taylor” Luzedetusinrisa (6 Feb 2017). https://mariammakambon.wordpress.com/2017/02/06/journey-of-a-soul-the-life-and-work-of-betty-blayton-taylor/

Lunning, Elizabeth and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book (The Print Council of America, 1996).

Smith, Melissa. “Betty Blayton Cofounded the Studio Museum and Taught to Hundreds. Now Her Own Work Is Getting a Blue-Chip Reevaluation.” ArtForum (9 Sept., 2021). Accessed 9 Sept., 2021. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/betty-blayton-art-and-educator-2006575

Souleo, “Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist” Hyperallergic (23 January, 2017). https://hyperallergic.com/343882/betty-blayton-taylor-reminiscence

Wyma, Chloe, “Betty Blayton; Elizabeth Dee” ArtForum (October 2017). https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201708/betty-blayton-71261

Yau, John “Another Chapter of Black Art History” Hyperallergic (5 June, 2021). Accessed 8 September, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/650425/cinque-gallery-another-chapter-of-black-art-history/

Notes

Magnetic Fields; Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today. 8 June - 17 Sept. 2017, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO., 13 Oct. – 21 Jan. 2018, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC., 5 May – 5 Aug. 2018, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, FL. Organized by Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Erin Dziedzic and Melissa Messina, co-curators. ↩︎

Karen Eminhiser-Harris, “Women of Color Find Their Rightful Place in the History of American Abstraction,” Hyperallergic (August 22, 2017). https://hyperallergic.com/396111/women-of-color-find-their-rightful-place-in-te-history-of-american-abstraction/ ↩︎

Blayton, Artist statement, 2006. Box 2, Folder 8. Betty Blayton-Taylor papers, 1929-2016, bulk 1970s-2000s. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↩︎

Betty Blayton. 20 June-20 July 2017, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, NY. In conjunction with Uptown,” 20 June – 20 July 2017, The Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York, NY. Souleo, curator. “Betty Blayton” Exhibitions. Elizabeth Dee Gallery. Accessed 24 May, 2019. www.elizabethdee.com/exhibitions/betty-blayton ↩︎

“Art; Betty Blayton,” Goings on About Town, The New Yorker. Accessed 24, May 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/goings-on-about-town/art/betty-blayton ↩︎

Sometimes written as Betty Blayton-Taylor, her married name. ↩︎

Oscar Blayton, personal communication with author, February 5, 2020. ↩︎

Oscar Blayton, personal email to author, May 1, 2020. ↩︎

“Jimmy” Blayton attended Moses Brown, Providence, RI and Oscar attended Williston Academy, Easthampton, MA as well, but finished their secondary school educations at the Palmer Institute. Oscar Blayton and Barbara (Blayton) Richardson, personal emails to author, May 1, 2020. ↩︎

James V. Hatch and Judy Blume eds. “Interview of Betty Blayton-Taylor by Halima Taha, November 9, 1997” Artist and Influence Vol.17:1-199 New York, NY: Hatch-Billops Collection Inc. (1998), 47. ↩︎

Souleo, “Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist” Hyperallergic (23 January, 2017). https://hyperallergic.com/343882/betty-blayton-taylor-reminiscence ↩︎

Oscar Blayton, personal communication with the author, 8 September, 2021. ↩︎

Chloe Wyma, “Betty Blayton; Elizabeth Dee,” ArtForum (October 2017). https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201708/betty-blayton-71261 ↩︎

Wyma, “Betty Blayton; Elizabeth Dee,” ArtForum. ↩︎

Hatch, “Interview of Betty Blayton-Taylor by Halima Taha, November 9, 1997” Artist and Influence Vol.17:1-199 New York, NY: Hatch-Billops Collection Inc. (1998), 53. ↩︎

In 1964 HARYOU merged with the Associated Community Teams (ACT) becoming HARYOU-ACT. ↩︎

A documentary introducing Charles White, Romare Bearden, Richard Hunt, Barbara Chase-Riboud, and Betty Blayton. FIVE Artists. Directed and produced by Vicki Kodama, 1971. The National Archives and Records Administration. https://archive.org/details/gov.archives.arc.50813 ↩︎

Betty Blayton, FIVE Artists. Directed and produced by Vicki Kodama, 1971. ↩︎

Souleo, “Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist,” Hyperallergic. ↩︎

The late Martha Gilbert Norris and Betty Blayton lived together for twenty years and worked together at the Art Carnival for ten. Martha Gilbert Norris, personal communication with author, 3 December, 2019. ↩︎

The Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Creating a Living Legacy (CALL) grant provides resources to help artists create usable documentation of their artworks and careers, manage their inventory of artworks, and start the estate planning process. “Creating a Living Legacy,” Artist Programs, Joan Mitchell Foundation, accessed 10 June 2019. https://www.joanmitchellfoundation.org/creating-a-living-legacy ↩︎

Magazine Cover featuring Betty Blayton Iconograph, 1970 oil collage on canvas, 39.5” diameter, Betty Blayton Lifetime Trust. “Black Women in the World of Work,” Contact (Fall 1973). Box 2, Folder 7. Betty Blayton-Taylor papers, 1929-2016, bulk 1970s-2000s. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↩︎

Mariamma Kambon, “Journey of a soul; the life and work of Betty Blayton Taylor” Luzedetusinrisa (6 Feb 2017). https://mariammakambon.wordpress.com/2017/02/06/journey-of-a-soul-the-life-and-work-of-betty-blayton-taylor/. ↩︎

“Creating Community: Cinque Gallery Artists,” 3 May - 3 July, 2021, The Art Students League of New York. ↩︎

John Yau, “Another Chapter of Black Art History” Hyperallergic (5 June, 2021). Accessed 8 September, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/650425/cinque-gallery-another-chapter-of-black-art-history/ ↩︎

Oscar Blayton, personal email to author, 3 November, 2021. ↩︎

Souleo, “Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist” Hyperallergic. ↩︎

Most of her artwork was then moved to storage, and the Betty Blayton-Taylor Lifetime Trust is now managed by her brother Oscar H. Blayton (Williamsburg) and nephew Omar Blayton (Boston). ↩︎

^26^Wyma, “Betty Blayton; Elizabeth Dee” ArtForum. ↩︎

FIVE Artists. Directed and produced by Vicki Kodama, 1971. ↩︎

Microscopic examination (Zeiss Axioscp.A1 with a HAL 100 illumination system) of a small sample from the tacking margin of Consume #2 identified the cotton fibers. Though other paintings were examined from the verso and certainly appear to be cotton as well, no samples were taken from the other works examined to confirm this. Other Blayton oil and paper on canvas tondos examined for comparison included Astro Turbulance (c. 1969) private collection, Transition (1971) private collection, Angels (1971) private collection (all examined February 2020) and World Within Worlds (1970) Betty Blayton Estate and Becoming (1974) Betty Blayton Estate (both examined March 2020). ↩︎

Gilbert, personal communication with author, 3 December, 2019. ↩︎

FTIR identified bands characteristic of calcium carbonate in an oil-based binding media. ↩︎

Oscar Blayton, personal communication with author, 3 December, 2019. ↩︎

FIVE Artists. Directed and produced by Vicki Kodama, 1971. ↩︎

No evidence of chalk has been found during examination of Consume #2. ↩︎

Exhibition Pamphlet, “Fifteen Women,” Taylor Art Gallery and Bluford Library at the North Carolina A&T State (1970). Eva Hamlin Miller, curator. Box 3, Folder 35 Betty Blayton-Taylor papers, 1929-2016, bulk 1970s-2000s. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↩︎

Omar Blayton, personal communication with author, 6 March, 2020. ↩︎

Marie-Claude Corbeil, Jean-Pierre Charland, Elizabeth A. Moffatt. “The characterization of cobalt violet pigments,” Studies in Conservation 40 Number 4 (2002), 244. ↩︎

Corbeil, 246. ↩︎

Corbeil, 237. ↩︎

FIVE Artists. Directed and produced by Vicki Kodama, 1971. ↩︎

In a journal entry, Blayton wrote: “Mon 3/3/12” “[item] (6A) Pearl Paint for Rice Paper,” confirming that by 2012 she was purchasing the paper from Pearls Paint in New York. The exact source of her earlier works has not yet been determined. Oscar Blayton, personal email to author, 23 August, 2021. ↩︎

Elizabeth Lunning, and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book (The Print Council of America, 1996). Using this reference standard, the color of the paper is most closely similar to Cream (2). ↩︎

Gilbert, personal communication with author, 3 December, 2019. ↩︎

Souleo, “Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist” Hyperallergic. ↩︎

“Betty Blayton, In Search of Grace” 8 Sept – 16 Oct, 2021, Mnuchin Gallery, New York. Curated by Sukanya Rajaratnam. ↩︎

“Reflectance Transformation Imaging”Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI). Accessed December 2019. culturalheritageimaging.org/Technologies/RTI/. ↩︎

(Hasselblad H6D Medium Format DSLR Camera, Broncolor Siros 800s RFS21 strobe light). ↩︎

Beth A. Price, Boris Pretzel and Suzanne Quillen Lomax, eds. Infrared and Raman Users Group Spectral Database. 2007 ed. Vol. 1 & 2. Philadelphia: IRUG, 2009. Infrared and Raman Users Group Spectral Database. Web. 20 June 2014. www.irug.org. ↩︎